In Haiti, violence has intensified and spread since late February, with young people among the hardest hit. Criminal groups like the G9 and G-Pèp coalitions —some with military-grade weapons and drug trafficking links— have attacked the country’s key infrastructure, including police stations and ports, as well as Port-au-Prince’s neighborhoods. The groups are increasingly recruiting young people, sometimes using coercion and threats.

Clean water, medicine, food, and electricity are scarce, which, for millions of children, limits their already precarious access to essential goods and services. Many schools have been forced to close across Port-au-Prince and the metropolitan area, leaving hundreds of thousands of children with no access to education. Human Rights Watch’s Nathalye Cotrino, who is documenting the crisis in Haiti, interviewed a number of youth from some of the hardest-hit Port-au-Prince communes, Cité Soleil and Delmas. Below are four of their stories.

Anne M., 15 years old: “We had to leave after a stray bullet hit me.”

“I’m very hungry, my stomach hurts, I haven’t eaten for days,” Anne M. (not her real name) told Human Rights Watch by phone in early April. She was standing in line with her family at a church in Port-au-Prince’s Delmas commune to receive food. This is how they have survived since fleeing their home on March 4, following two harrowing days of violence.

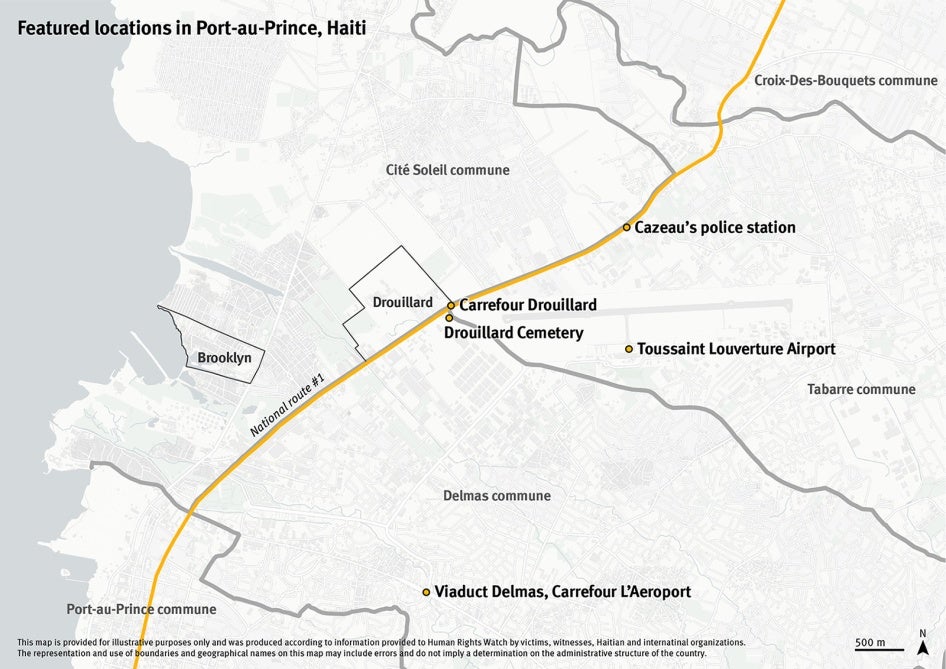

On March 2 and 3, criminal groups broke into Port-au-Prince’s two largest prisons, freeing thousands of detainees. They also attacked at least 22 police stations, including the Cazeau police station close to Anne’s home, on the outskirts of Cité Soleil.

On March 2, Anne sheltered at home with her mother and 12- and 9-year-old brothers. “We had not eaten all day because since the morning the members [from the G9] had been shooting […] we couldn’t go out,” she said.

That evening, her mother got some rice from a neighbor. Anne and her brothers were happy to have something to eat, but their joy was short lived. “When we started to eat, we heard more gunshots, very close, very loud,” she said. Anne’s mother ordered her to hide under a table before throwing herself over her youngest son. Then it happened. A bullet penetrated the wall and hit Anne, passing through her right arm, near her shoulder.

“I just felt a lot of pain and I saw a lot of blood,” she said, her voice breaking. “I was very scared, I started to cry but my [12-year-old] brother covered my mouth to keep me quiet for fear that [the shooters] would enter the house.”

She paused. “The last time [G9 members attacked our home] some months ago, four of them raped my mother. I was able to save myself because I ran away and hid in another house.”

Attacks by criminal groups on hospitals and clinics, as well as looting and shortages of medical supplies, meant healthcare facilities near Anne had closed. Her family did not have the money to travel to other facilities or pay for medicine. They also feared run-ins with criminal groups, which control ever-increasing areas of Haiti’s capital. On March 4, they fled their home, leaving behind their few belongings, in search of shelter in the nearby commune of Delmas. There, they met a Christian priest who treated Anne’s injured arm. Since then, they moved through several informal camps for displaced people, seeking shelter and food. Despite the efforts of local and international humanitarian organizations, as of April, Anne and her family still lack access to essential services, including education.

“We have not been able to go to school for two years because of them [the criminal groups]. Our school was closed because of them, the teachers couldn’t even go in, for fear that something bad would happen to them or us,” Anne said.

Criminal groups tried to recruit her brother, using the scarcity of food, water, and other necessities as leverage. “My 12-year-old brother has been asked [by G-Pèp members] to go with them. They have offered him money and food,” Anne said. “He is thinking about it, but he is afraid of guns.”

“I am talking to you because... maybe then our voice could be heard. And maybe someday, someone could do something to stop this violence, to stop this suffering.”

Marie C., 16 years old: “I miss my sister very much she was the only one I had after my parents were killed.”

“Please don’t say my name, I’m very scared,” Marie C. (not her real name) told me over the phone.

Until early 2023, Marie lived with her parents and 21-year-old sister in Brooklyn, Cité Soleil, one of the poorest and most vulnerable areas of Port-au-Prince. She said that G9 members shot and killed her parents on the way home from the market, where her mother sometimes sold rice with meat. Marie vividly recalls the days that followed: the sisters had no food, electricity, or water. In desperation, they fled to their uncle’s home in the nearby neighborhood of Drouillard.

Any semblance of peace they gained in Drouillard ended on March 8.

“It was a Friday, I remember, because that day was my sister's birthday. We left the house early, we wanted to go to the market to buy something for her birthday,” Marie said. Then, the sound of gunshots echoed from the main road, Route 1. “I wanted to go back, but my sister wanted to buy her present [… .] She insisted, she told me that they [the G9 members] were always shooting, that we should stay low and nothing would happen to us.”

But when they tried to cross the road, a bullet hit her sister in the leg. “She fell to the ground and shouted at me, ‘Run, run save yourself,’ [… .] I saw that she was bleeding a lot, but they kept shooting.”

Marie continued her story in tears, her voice breaking. “I ran out and hid in some [bushes], I couldn’t see her, I didn’t know what to do. The shooting continued, I curled up and began to pray.”

Marie does not know how long she hid, but when she stopped hearing the shots she crawled to the avenue, searching for her sister. She could not find her. “I ran to my house. My uncle was very worried [... .] I told him what happened [...] we cried a lot [...] he scolded me for not having returned.”

That afternoon, their uncle went in search of her sister. A neighbor told him that someone had rescued her and taken her to another neighborhood for medical care. A few days later, her uncle found her. When he came back, he told Marie that her sister was recovering, but would not reveal her location. “He told me that it was better for her not to come back, because the criminal group members could do something to her [… .] He didn’t tell me where she was.”

“I have not seen her since,” Marie said. For Marie, her sister was the only person she felt she could count on. “[Now] I have to live on my own.”

Joseph F., 16 years old: “I don’t want to die like my friends have done, with a gun in my hand.”

Joseph F. (not his real name) is one of the 180,000 children displaced by violence in recent months. He lives on the streets of Port-au-Prince.

He had been living with his aunt, his only family, in the Drouillard neighborhood of Cité Soleil for six years, since his mother’s death. Today, he has no idea where his aunt is, if she’s dead or alive. “I don’t know what happened to her,” he said.

Joseph last saw his aunt before he went to work on March 1, the day criminal groups launched coordinated attacks against the Toussaint Louverture airport in Port-au-Prince. Around noon, Joseph’s boss at the auto repair shop, located near the airport, told him to go home for the day, since there was not much work.

“When I was arriving at Carrefour Drouillard [a crossroad], I saw many armed criminal members and heard many gunshots. They were burning tires blocking the road. I ran to try to cross the road before everything got more complicated, and that’s when I was shot.”

The bullet hit Joseph’s right side, just missing his ribs. The wound bled for nearly a week, and as Joseph could not afford hospitals or medication, he used alcohol and bandages to treat it. Still, he was not that scared, he said. Accustomed to Haiti’s pervasive violence, he was used to blood. “I had already seen blood because several of my friends had been injured and killed in gang fights [but] I had managed to avoid getting hurt.”

When the gunfire stopped, Joseph chose not to return home, and instead hid in the nearby Drouillard cemetery. He didn’t want criminal group members to find him. Many of Joseph’s friends had joined criminal groups out of desperation, and these groups were also pressuring him to join. Members told Joseph he would be part of “a popular cause against the bad government, that it is not to harm people but to fight and make the revolution,” he said. But “I don’t believe any of that. [The G9 members] had threatened me [in the past], they told me that if I don’t join them something could happen to me or my aunt.”

UNICEF has found that Haiti’s criminal groups are increasingly using and recruiting children, and that many have children in their ranks.

Joseph’s day-to-day life is precarious. “I have been sharing a dirty old mattress for a month in a square where there are others like me who have fled their homes. We only have a blanket and a plastic sheet to cover ourselves,” Joseph said over the phone as he sat under the sun, waiting for a meal. He hoped to shelter under a tent in the yard of a nearby house, where several other displaced people were staying. He often goes hungry, like nearly half of Haiti’s population, and has not been able to attend school for four years.

Despite these hardships, Joseph is clear: he doesn’t want to die like his friends.

Joseph misses his home and his aunt, who looked after him even before his mother died, when she would go to work. Even so, he said, crying, it is “better to not go back.”

Guerry Y., 17 years old: “I don’t want to suffer more, I want a better life for my baby.”

“I don’t know if my friend died or survived, I survived by a miracle.”

This is how Guerry Y. (not his real name), a 17-year-old resident of the Delmas area in Port-au-Prince, began his story.

On March 4, Guerry and his friend Louis were on the street in Delmas, trying to sell car parts to earn money for their families. They went out that morning despite the sound of gunshots which, Guerry said, had become part of their daily lives.

“We were on a corner near the Carrefour L’ Aéroport viaduct when we started to hear a lot of gunfire from automatic weapons all around [… .] I knew the gangs were furious and were attacking the prisons, the airport, and everything related to the government, but I didn’t think they would attack there. We ran away, but a bullet hit my friend.”

Guerry was breathless as he explained what happened: “I only saw him fall to the ground, face down. I went back to help him, but the bandits kept shooting. He was screaming in pain, and when I picked him up, I saw he was bleeding from his back. I carried him as best I could and moved to cross the avenue. The bullets kept coming, and I was very scared, very, very scared. I don't know how I managed to survive.”

A man passing by on a motorcycle offered to take Louis to a hospital. “Since that day, I haven’t heard from him,” Guerry said.

Guerry then rushed home to the room he shared with his father, 14-year-old brother, and grandmother. His father, who worked at the airport square, arrived home an hour later, scared and hoping his family was safe. The shooting continued on-and-off for nearly three hours. Gripped by fear, Guerry and his family hid under their mattresses.

“It was almost night when we started to smell something burning and heard a lot of shouting in the distance. When I went out […] neighbors told me to leave because they, the bandits, were going to burn us inside the houses.”

Guerry went back and told his father, and the whole family rushed outside. But it wasn’t the neighborhood homes that were on fire. “We saw the smoke […] it was the Carrefour L’ Aéroport police station. They had attacked the police station and set it on fire.” Human Rights Watch later confirmed that, after several hours of fending off the G9 attackers, the police officers realized they were outnumbered and outgunned, and evacuated to safety.

Guerry and his family fled their home, leaving all their belongings behind. For a few days, they stayed with a friend of Guerry’s father. Then, his father, brother, and grandmother left for Gonaives, about 90 miles north of Port-au-Prince, where they had more family.

Guerry stayed behind with his girlfriend, who is seven months pregnant. “I couldn’t take her [to Gonaives], because she takes care of her sick mom and a younger sister.”

Guerry, who now has no work, goes every day to a church for food.

“We don't want more violence,” he said, before screaming in desperation. “We want opportunities. I don't want to suffer more, I want a better life for my baby.”

“I am just asking that someone help us,” Guerry said.

***