Summary

On April 7, 2016, soon after the end of evening prayers, Sadia, 27, heard her husband calling her to come down to the street. As she got to the door, however, he stood flanked by two men, blocking the exit. On her husband’s order, his companions doused her with nitric acid. “My husband stood watching as my dress fell straight off and my necklace and earrings melted into my skin,” Sadia said. After four surgeries and almost four months at Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Sadia lost both her left ear and left eye. “He was trying to kill me,” she said when Human Rights Watch met her a year later.

Acid attacks are one particularly extreme form of violence in a pattern of widespread gender-based violence targeting women and girls in Bangladesh. In fact, many of the women interviewed for this report endured domestic violence, including beatings and other physical attacks, verbal and emotional abuse, and economic control, for months or even years leading up to an attack with acid. For instance, during the 12 years that Sadia was married before the acid attack, her husband beat her regularly and poured chemicals in her eyes three times, each time temporarily blinding her.

According to a 2015 survey by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), over 70 percent of married women or girls in Bangladesh have faced some form of intimate partner abuse; about half of whom say their partners have physically assaulted them. Bangladesh human rights group Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) reported that at least 235 women were murdered by their husband or his family in just the first nine months of 2020. According to another prominent Bangladesh human rights group, Odhikar, between January 2001 and December 2019, over 3,300 women and girls were murdered over dowry disputes. These numbers, however, are based on media reports and are likely only a fraction of the true levels of such violence.

Violence against women and girls in Bangladesh appears to have further increased during the Covid-19 pandemic with NGO hotlines reporting a rise in distressed calls. For instance, the human rights and legal services program of BRAC, a major nongovernmental organization in Bangladesh, documented a nearly 70 percent increase in reported incidents of violence against women and girls in March and April 2020 compared to the same time last year.

This crisis comes at a time when Bangladesh is marking the anniversaries of two landmark pieces of legislation on gender-based violence and entering the final phase of its national plan to build “a society without violence against women and children by 2025.” In spite of this goal, this report finds that the government response remains deeply inadequate and barriers to reporting assault or seeking legal recourse are frequently insurmountable.

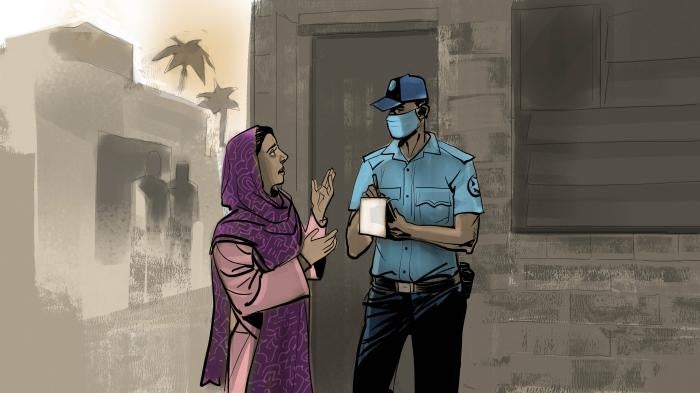

Sadia says she never felt safe reporting the violence her husband committed against her during their 12-year marriage because she did not trust the police to respond properly, and feared that it would only enrage her husband and place her at further risk because she had no support. This lack of trust in police is tragically common, and is compounded by the fact that shelter services are so limited in Bangladesh that for most survivors there is nowhere to go to escape abuse.

At the same time, violence against women and girls is so socially normalized that survivors often don’t feel violence against them is something that would be taken seriously or is worth reporting. When asked if she would file a police report after her husband forced her to drink acid, Joya, 19, said her father told her “maybe later.” “What’s the point in complaining?” she asked. The same 2015 BBS survey that found that over half of married women and girls had suffered some form of abuse, also found that over 70 percent of these survivors never told anyone and less than three percent took legal action. As one women’s rights lawyer put it: “Society thinks domestic violence is silly violence, that it’s something that normally just happens in the family.”

This report draws on 50 interviews to document the deep and systemic barriers to realizing the government’s goal of a society without violence against women and children. We interviewed 29 women from six of the eight divisions of Bangladesh who were survivors of gender-based violence, including acid attacks, as well as women’s rights activists, lawyers, and academics to understand the deep and systemic barriers to legal recourse and protection that survivors face.

Among Bangladesh’s efforts to combat gender-based violence, the government’s success in addressing acid violence stands out in particular. Since passing robust legislation alongside effectively coordinated civil society campaigns, acid attacks dropped dramatically from 500 cases in 2002 to 21 recorded attacks in 2020, at time of writing.

As one lawyer explained, acid cases are the ones where it is “easiest” for survivors to gain justice and support because of an active, well-coordinated, civil society response and because the government has focused significant efforts. But even in these cases, legal recourse remains unattainable for most survivors of acid violence.

This shortcoming points to one of the most glaring failures in the government’s efforts to address not only acid violence, but gender-based violence more broadly: the immense barriers to securing justice. As a lawyer from the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers Association (BNWLA) said: “The number one obstacle to stopping gender-based violence is the criminal justice system.”

This report finds that not only is the criminal justice system failing women and girls who have survived gender-based violence, but that additional failures in response, protective measures, and services seriously hinder survivors’ ability to access the justice system in the first place.

Poor Enforcement of Laws

Bangladesh has taken some important steps to address violence against women and girls.

In 2000, in partnership with the Danish government, Bangladesh inaugurated the Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence Against Women (MSPVAW) and developed a comprehensive National Action Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children. Bangladesh also enacted the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain (Women and Children Repression Prevention Act) 2000, replacing the landmark 1995 act under the same name, aimed at addressing a wide range of violence that disproportionately impacts women and children.

When acid attacks peaked at nearly 500 reported cases in 2002—the vast majority of which targeted women and girls—public pressure and concerted activism by women’s rights organizations and survivors spurred the government to enact two laws: The Acid Offense Prevention Act, 2002 and The Acid Control Act, 2002.

In 2010, Bangladesh passed the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act (DVPP Act), an important step forward in defining domestic violence outside dowry violence to include physical, psychological, sexual, and economic abuse. The act also laid out important protections for victims and criminalized the breach of protection orders.

However, as Bangladesh marks the 20-year anniversary of the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000 and the 10-year anniversary of the DVPP Act, it is clear that implementation of these plans and laws is falling drastically short. As a lawyer from Naripokkho, one of the country’s oldest women’s rights organizations, explained: “There are so many wonderful things you will see in the national action plan, but when you look in the field, it isn’t happening.”

Violence Against Women and Girls during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Like many other parts of the world, violence against women and girls in Bangladesh increased during the Covid-19 pandemic. The human rights and legal services program of BRAC, a major nongovernmental organization in Bangladesh, documented a nearly 70 percent increase in reported incidents of violence against women and girls in March and April 2020 compared to the same time last year. In April, a man livestreamed himself on Facebook while he hacked his wife to death with a machete. In May, a man reportedly struck his wife over the head with a brick, ultimately killing her, because she didn’t get cold water from the refrigerator during iftar. At the same time, access to legal recourse and urgent protection measures were cut short, bringing into sharp relief the faults of an already failing system.

On March 26, 2020, the government declared a nationwide “general holiday”— essentially a nationwide lockdown to stop the spread of Covid-19—that was extended until May 31, 2020. A study surveying 2,174 women towards the end of this lockdown, published in The Lancet in August, found that during this time women experienced an increase in emotional, sexual, and physical violence. In fact, more than half of those who reported physical violence, such as being slapped or having something thrown at them, said that this violence increased since the onset of the lockdown. For some, this domestic violence was new. Manusher Jonno Foundation, for instance, surveyed 17,203 women and children in April, and found that of the 4,705 women and children who reported incidents of domestic violence that month, nearly half said this was the first time.

Even as the already high level of violence against women and girls increased during the pandemic, government policies made it even more difficult for survivors to access urgent support and legal redress by temporarily shutting down court services for victims of gender-based violence, closing already-limited shelters, and by turning away survivors at police stations.

The Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) reported that most callers to their hotline said that they were trapped, unable to escape violence at home because they could not travel to a friend or relative’s home during the lockdown, and there were no accessible government shelters as an alternative. In one example, BLAST documented a case in which a woman left her home on April 25, 2020, because she said her in-laws were physically abusing her. But when she got to the nearest police station in Gazipur, they had nowhere to bring her. She slept in the police station until her brother arrived from Barishal— a district about 250 kilometers away— to pick her up. ASK reported that women and girls seeking to file domestic violence complaints with police were turned away with officers refusing to accept General Diary complaints (police reports) or provide any assistance.

Failure in Accountability

Perpetrators of gender-based violence are rarely held to account in Bangladesh.

According to data provided by the Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence Against Women, of the over 11,000 women who filed legal cases through one of the government’s nine One-Stop Crisis Centers for women and girls, only 160 saw a successful conviction, at time of writing. Keeping in mind that the vast majority of women and girls in Bangladesh who face gender-based violence never tell anyone, it is discouraging that of those who do seek help—and additionally pursue legal recourse—there is only about a one percent likelihood that they will successfully obtain legal remedy.

According to case data collected from 71 police stations by Justice Audit Bangladesh, a joint program between the Bangladesh government and the German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), in 2016, of the over 16,000 cases of violence against women under investigation, about 3 percent resulted in a conviction, as compared to a 7.5 percent conviction rate of other cases under investigation during that same period. While a 7.5 conviction rate is also low, it shows that the barriers faced by all Bangladeshis in seeking legal recourse through the criminal justice system are further compounded for women and girls.

A 2015 BRAC University study seeking to explain the low conviction rate of cases filed under the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000, compiled case records from the special Nari-o-Shishu tribunals in three districts from 2009-2014 and found that conviction rates have near-steadily dropped from about 2 percent to 0.42 percent. According to the Justice Audit, in 2016 courts disposed of just over 20 percent of the over 170,000 open Nari-o-Shishu cases that year, convicting only 0.5 percent of those accused.

Despite relative successes in the campaign against acid violence, survivors face similarly low conviction rates. In fact, as cases of acid violence have decreased, so have conviction rates. Since the passage of the laws in 2002, only about nine percent of cases recorded by the Police Headquarters’ Acid Crime Case Monitoring Cell up to 2015 had resulted in convictions. But this overall percentage includes an unusual 20 percent spike in convictions in 2002 when the acid laws were first passed. In the years since, the rate has quickly fallen. Overall, considering cases for the most recent five years for which the police have released data, the conviction rate is actually three percent. Since then, the police cell stopped recording case outcomes.

These convictions only account for cases that were filed by police and reported to the Acid Crime Case Monitoring Cell. In reality, the likelihood that a survivor will see their attacker held to account is even lower because many cases never make it to the trial stage.

Low conviction rates aside, the failures of the judicial process described below raise serious concerns. Over two decades since its creation, Selina Ahmed, then-director of the Acid Survivors Foundation (ASF), told Human Rights Watch in September 2019 that access to justice was the organization’s greatest enduring challenge in its mission.

Acid Violence in Bangladesh

Over the last 20 years, according to ASF, there have been over 3,800 reported cases of acid violence in Bangladesh, with the vast majority of attacks perpetrated by men targeting women or girls who they know. Inextricable from gender inequality, acid attacks often occur within a pattern of ongoing domestic violence, in response to rejection of sexual advances or a marriage proposal, as a punishment for seeking education or work, or as a form of retribution in land or dowry disputes.

When concentrated acid is thrown on a person it instantly melts through the skin, often down to the bone, dissolving eyes, ears, nose, lips, and skin. At the outset, victims are at high risk of infection—particularly in places like Bangladesh where accessible and adequately sterile health facilities for burn victims are nearly nonexistent. In the medium term, survivors often require surgical interventions to restore mobility. Burn wounds can take up to a year to heal and, without adequate medical care, can leave thick keloid scars that contract and can cause lifelong physical harm severely restricting basic movement. Even with access to proper medical care—which most of the people we interviewed did not have—blindness, hearing loss, and other disabilities are common.

Existing government facilities for burn treatment are overburdened and primarily centered in Dhaka, the capital city, and thus largely inaccessibly to rural populations. All of the survivors interviewed for this report expressed suffering severe pain. The Medecins Sans Frontieres Clinical Guidelines for burn care recommend morphine. Yet, although morphine is on the World Health Organization (WHO) List of Essential Medicines, oral morphine is only available in Dhaka, and even there it is expensive and in short supply. In reality, this means that many survivors endure severe pain without sufficient medication, which only exacerbates the trauma.

Acid violence is rarely directly fatal. Rather, victims live on with physical, emotional, economic, and social suffering. Victims are often left with severe and permanent disabilities and may depend on family members for ongoing care, sometimes for the rest of their lives. Despite this, some women said that after they were attacked, their families or husbands abandoned them. For instance, Shammi, 30, said that after her husband attacked her, she had nowhere to go and nobody in her family would take her in. She eventually went to stay at her sister’s home where they kept her in a room which she described as a small closet. “I was abandoned there like an animal,” she said.

Disability resulting from an acid attack can severely impact a woman’s ability to perform physical work that she previously may have been able to do, thus cutting off an important component to financial independence. Rezwana, 28, who was attacked by her husband, said that she used to work part-time in a garment factory but now she says her mobility has been restrained by keloid scars, making the mobility and dexterity required for sewing difficult, if not impossible. She said because of this she can no longer work and is now financially dependent upon her brother and had to move to a slum because she could not afford rent.

Acid attack survivors in Bangladesh also face cultural stigma that exacerbates the discrimination they face as people with disabilities. For instance, Shammi explained that she could no longer find work because, she said, “socially, people are afraid to see me.” Farida, 35, whose husband attacked her after she rejected his sexual advances, said that at first her own children were “terrified” of her and that both she and her children have “faced backlash from people in the community because they believe [she] is unlucky.”

Nearly all of the survivors Human Rights Watch spoke with described feelings of constant high-anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, psychological distress, and enduring fear. Sadia described to Human Rights Watch the feeling of fear and anxiety when sleeping in the room where her husband attacked her: “I feel I sleep in my own deathbed,” she said. Sahana, whose husband attacked her with acid and who is now struggling financially, described sometimes sleeping at the train station and considering rolling onto the tracks to be hit by a train. “What’s the point in going on?” she asked. Salma, who feels she has been a burden to her family since the attack because of the medical expenses, said that she felt “maybe it would be better if I died on the operating table.” “Sometimes I ask Allah to just take me away,” she said.

These psychosocial impacts are exacerbated by what is often a prolonged and expensive justice process, during which victims can face re-traumatization, recurring medical fees, economic hardship, stigma, lack of support, and sometimes threats to drop their case.

In light of the government’s failure to uphold its commitments, ASF has taken on the lion’s share of providing for survivors’ basic needs. ASF has provided free immediate and long-term medical care, legal aid, psychosocial services, and socioeconomic rehabilitation to thousands of acid attack survivors in Bangladesh over the two decades they have been in operation —services often unavailable to victims of other forms of gender-based violence because of under-resourced groups and limited state facilities. However, as the number of acid attacks have decreased, attention to acid violence has waned and donors are losing interest, leaving ASF with fewer resources to fill these needs.

Institutional Barriers

When it comes to legal recourse and protection in acid cases, the justice system falls dramatically short and many survivors of acid violence face the same barriers that often obstruct women and girls from even filing a case in the first place. These obstacles combined with endemic corruption, gender bias in the legal system, and a lack of implementation of the laws, make the pursuit of legal remedy practically unobtainable.

Police, at times, outright refuse to file a First Information Report, a charge sheet, or conduct a serious investigation, particularly in claims that are related to domestic violence or when the perpetrator is influential. Women or girls who were subjected to domestic violence leading up to the acid attack often could not access services and did not feel comfortable reporting the incidents to police because they feared both that the police would not take their case seriously, and that their husband or in-laws would retaliate against them for having reported the crime.

For most women and girls in Bangladesh, access to safe shelter for protection and support is lacking with an estimated 21 government-run shelters and 15 NGO-run shelters for survivors of gender-based violence in a country with over 80 million women and over 64 million children. This is deeply inadequate considering that most women in Bangladesh face some form of violence in their lives. Of those available, the short-term shelters only allow for a stay of up to a few days and most shelters have strict rules which exclude some women from being able to access them at all. Some have eligibility requirements, such as requiring a court order and many of the NGO shelters are only for victims of particular types of violence such as sex trafficking; others don’t allow children, and most don’t allow male children above a certain age.

One of the most common reasons that criminal investigations and prosecutions in cases of acid violence—and cases of violence against women and girls more broadly—result in acquittal or remain in open investigation for years on end, is a lack of sufficient evidence. This is often a result of poor police work and public prosecutors’ failure to actively pursue the case, coordinate with investigators, or secure witnesses. In a 2015 BRAC University study on the low rate of conviction in criminal cases of violence against women, insufficient evidence from weak police investigations was cited as one of the key reasons for low convictions rates.

Bangladesh’s main laws on violence against women all stipulate that cases should be resolved in a timely manner, with maximum case disposal periods ranging between 60 to 180 days. In reality, cases often go on for years.

As this report demonstrates, as cases drag on, the costs and emotional toll of continuing combined with fear of or threats from perpetrators can pressure complainants into negotiating out of court for a resolution that doesn’t adequately reflect the harm they have suffered. In a 2016 Justice Audit survey of One-Stop Crisis Centers, case workers said that court cases usually took between five to six years to resolve whereas illegal settlements can be concluded in a matter of months.

One of the problems with the criminal justice system most frequently cited by legal practitioners was the prolonging of cases with too many adjournments, most often due to the non-appearance of witnesses, including the victim. However, without a witness protection law or reliable access to safe shelter, participating in a trial is often too dangerous for women or girls seeking legal recourse, especially from their husband or another family member. Additionally, public prosecutors are often not properly trained in criminal law and fail to contact witnesses or ensure they are aware they are expected and have the means to safely travel to appear in court.

Throughout the legal process, survivors repeatedly come under pressure from perpetrators or even their own families to withdraw their complaints and some described fearing for their lives because Bangladesh still has no victim or witness protection law. For example, Taslima, who was attacked with acid in April 2018 by a relative after a dispute, has moved with her family outside of Dhaka since they are facing threats from the perpetrator’s family. According to Taslima, the perpetrator’s lawyer even threatened them, saying that if the alleged perpetrator is sent to jail “nobody in your family will live.” Nearly 90 percent of legal practitioners surveyed by the Justice Audit said that the measures for the protection of vulnerable witnesses and victims of crime, especially women and girls, were not adequate.

Pressure from powerful perpetrators, or their allies, on not only victims but also legal professionals, police, and other witnesses, poses a significant obstacle to legal recourse. In a 2016 Justice Audit survey of legal practitioners, over half of public prosecutors, magistrates, and judges said that they feared for their personal safety. Overall, over 80 percent of the 237 magistrates surveyed said that there had been credible threats made to magistrates in 2016 alone.

The financial and emotional strain caused by a lengthy legal process, including travel costs and legal fees, as well as the demand for bribes, is particularly harmful for victims. Moreover, Nari-o-Shishu tribunals (the violence against women and children tribunals) tend to be in the main cities, adding to the additional and significant obstacle of travel for women and girls in rural parts of the country—where the majority of the population lives. The problem is compounded for women who are financially dependent upon a husband who may have committed the attack in the first place. A lawyer from the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers Association explained that as time goes on, “victims’ families can’t keep going, perpetrators can threaten the victim to drop cases, evidence is lost over time, witnesses drop out over time. Essentially, when cases are delayed, justice is denied.”

Bangladesh is currently facing a backlog of around 3.7 million criminal cases. Without any centralized tracking system, there is no way to ensure processing of and access to legal records, including in gender-based violence cases. As one lawyer from Naripokkho said, “When the case goes to higher courts, it gets lost. Even for us it is often not possible to find the status of a case. If it is hard for us, how will a survivor learn the status of their case?” The lack of transparency and organization enables a system of informal “fees” in order to access legal information.

Bangladesh should take seriously its obligation under international law and its own constitution and domestic laws to prevent, investigate, prosecute, and punish those responsible for violence against girls and women, and assist survivors. It should undertake serious prevention efforts, such as comprehensive education and awareness raising campaigns; and provide comprehensive services for women and girls seeking to escape or recover from violence. The government should act to weed out the incompetence and corruption throughout the criminal justice system, ensure that public officials perform their duties, and hold to account those who fail to do so.

Key Recommendations

- Develop stronger prevention mechanisms, including through comprehensive education in schools on consent, sexuality, and relationships; media outreach; and awareness raising campaigns for women and girls about their rights, including under the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000 and the DVPP Act.

- Increase access to support services across the country, including providing accessible and safe shelters for survivors of gender-based violence in every district, without requiring court orders to stay or restrictions on children.

- Provide sufficient training to public prosecutors and police on standards of criminal investigations, particularly in relation to working with survivors of gender-based violence.

- Create an online centralized filing system for all gender-based violence cases and ensure that relevant case information and reports are freely available and accessible to all parties to the case, as appropriate.

- Pass and implement an effective victim and witness protection act, drafted in consultation with Bangladeshi women’s rights organizations.

Methodology

Research for this report examining barriers to justice in cases of violence against women and girls, in particular focusing on acid assault cases, was conducted from June 2017 to June 2020.

This report is based on interviews with 37 survivors of acid violence from six of the eight divisions of Bangladesh, 29 of whom were women.[1] We also interviewed 13 lawyers and NGO experts working on acid violence, violence against women and girls, and legal reform in Bangladesh.

While this report broadly discusses barriers to justice and support for survivors of gender-based violence, it does not separately address sexual violence and harassment, which is an immense problem in Bangladesh.

Interviews with survivors were conducted in Bangla through an interpreter either at the Acid Survivors Foundation (ASF), a local NGO, or in the interviewee’s home. Only the interviewee, translator, Human Rights Watch researcher, and sometimes a social worker from ASF were present. Steps were taken to minimize re-traumatization, including by using specialized interviewing techniques. If the details of the case were already known from legal documents or otherwise, the researcher avoided asking the survivor to recount the actual attack. Human Rights Watch also ensured that all interviewees had the ability to contact support services from the Acid Survivors Foundation in case of any follow-up concerns.

All interviewees were advised of the purpose of the research and that the information they shared would be used for inclusion in this report. They were also informed that Human Rights Watch could not provide any direct legal, medical, or monetary assistance besides cost of transportation incurred due to participation in the interview. Interviewees were informed of the voluntary nature of the interview and that they could refuse to answer any question and that they could terminate the interview at any point.

In order to protect interviewees from potential retribution, names and identifying details have been changed in some of the cases described in this report. Names of all survivors quoted in this report and named alleged perpetrators are pseudonyms.

Human Rights Watch sent letters on September 17, 2020 to the Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence Against Women, the Ministry of Women and Children, the Ministry of Social Welfare, and The Ministry of Law and Justice, and on September 21, 2020 to the National Acid Control Council at the Ministry of Home Affairs, sharing initial findings and requesting input for inclusion in this report. We requested a reply by October 14, 2020 in order to include the response in the publication of this report, but received no reply as of time of publication.

I. Government Responses to Violence Against Women and Girls in Bangladesh

The Bangladesh government has taken a variety of initiatives and passed significant legislation to address violence against women and girls, actions that are key to fulfilling the government’s commitment to meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.[2] This includes reaching targets and indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals on Gender Inequality and on Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions.[3] Despite notable progress, this report finds that without proper implementation, women and girls are often unable to seek legal remedy or protection under these laws and perpetrators of gender-based violence are rarely held to account.

Legal Framework

The government of Bangladesh has passed significant legislation aimed at preventing and ensuring legal recourse for the various forms of violence against women and girls in Bangladesh, and assisting survivors.[4] In the current and final phase of the National Action Plan on Violence Against Women, discussed below, relevant ministers are expected to coordinate to ensure that these are properly implemented. However, women’s rights activists and lawyers said that there are significant gaps in enforcement, coordination, and awareness.

Acid Legislation

The Acid Offense Prevention Act and Acid Control Act enacted in 2002 were significant, not only in establishing a regulatory framework for the sale, distribution, and use of acid, but also in holding perpetrators of acid violence to account and putting in place provisions for social services.[5] Following the passage of these laws, two sets of rules were established in 2004 and 2008, further specifying the details of regulation and commitments by the government to provide medical, legal, and rehabilitation support to survivors.

The Acid Offense Prevention Act, 2002

The Prevention Act outlines punishment for perpetrators of acid violence with imprisonment between three years to life and, in some cases, the death penalty.[6]

Notably, the act includes specific provisions aimed at ensuring that a fair trial is held with minimum delay. Section 14 establishes that any offense under the act shall be considered cognizable, meaning that the investigating officer can file a First Information Report (FIR) and begin an investigation without first seeking authorization from the court.[7] Section 11 stipulates that investigations should be completed within 30 days from the filing of a complaint.[8]

Once the hearing of a case begins, courts must “continue every working day consecutively until its conclusion,”[9] concluding within 90 days of the court’s receipt of the case.[10] In the case that the accused has absconded—which is common in acid attack cases—and the court determines that “there is no immediate prospect of arresting” the accused, the court may proceed with the trial in the absence of the alleged perpetrator.[11]

The act also classifies acid offences as non-compoundable and non-bailable. This is particularly important because the law criminalizes any compromise between the complainant and the accused to have the charges dropped, a common practice when the perpetrator is able to threaten the victim. Section 15 establishes that in order to be released on bail, the complainant should have the opportunity to participate in the hearings.[12]

Like the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000 and the DVPP Act, the Acid Offense Prevention Act, 2002 establishes measures to ensure witness protection: Section 16(5) states that witness statements may be taken in private and Section 28 outlines provisions for safe custody “in a specified place or in the custody of any other person or organization considered proper by the Tribunal.”[13]

However, Bangladesh has no specific law or program for witness protection, despite drafts proposed by various women’s groups. The penal code only broadly criminalizes intimidation. [14] ASF reported that “in the majority of cases it is very difficult to ensure witnesses will testify mainly for security concerns.”[15] Women’s rights lawyers said that the lack of a witness protection program is a key obstacle in seeking legal recourse in cases of gender-based violence.[16]

The Acid Control Act 2002

The Acid Control Act of 2002 established three institutions— The National Acid Control Council (NACC) and the National Acid Control Fund (NACF) at the federal level and District Acid Control Councils (DACCs)— under the Ministry of Home Affairs, in charge of ensuring that survivors have access to treatment, rehabilitation, and legal aid promised under the Acid Law and to promote awareness-raising campaigns.[17] However, a 2015 report by the Acid Survivors Foundation found that these organizations were meeting rarely, and if they did meet, they were failing to sufficiently follow through with their duties.[18] As of July 2019, according to activists, the National Acid Control Council had not met in three years and the district level meetings were simply not taking place.[19]

The Medical, Legal Aid and Rehabilitation of the Persons Affected by Acid Rules, 2008

Under the 2008 rules, when a person is attacked with acid, and if they are seen at a hospital, a chain of information-sharing is essentially meant to be activated between the doctor, police, the local social welfare officer, and the chairman of the district council in order to ensure that the survivor receives the range of support that they require.[20]

While this legislation is an important step, these procedures are not always followed, say activists. While doctors will inform police of an acid attack, police frequently refuse to file a case, let alone ensure that the survivor is receiving critical social services.

Section 8 of the 2008 rules establishes that there shall be government-provided rehabilitation centers for acid attack survivors, administered by the district social welfare officer. The chairman of the District Acid Control Council is responsible for supervising “whether the rehabilitation centre is properly operating.”[21] In reality, there are no government-run rehabilitation centers for acid attack survivors and the Acid Survivors Foundation provides the majority of medical care to acid survivors without financial support from the government.

Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000

The Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain (Women and Children Repression Prevention Act), 2000, is a landmark piece of legislation aimed at addressing a wide range of violence including trafficking, abduction, burning, rape, dowry violence, and other crimes that disproportionately impact women and children.[22] The law also established special Nari-o-Shishu tribunals to prosecute such cases. There are currently 95 Nari-o-Shishu tribunals throughout the country.[23]

The passage of the law was a hard-won victory for women’s rights organizations in Bangladesh. However, two decades later, awareness of the law still appears to be lacking. A lawyer from Naripokkho explained that even “police are unaware of the Nari-o-Shishu and survivors don’t know what their rights are under the law.”[24]

Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2010

Domestic violence intersects with acid violence in Bangladesh. Indeed, a 2010 study on socio-demographic characteristics of acid victims in Bangladesh found that 90 percent of victims were women or girls and that 80 percent of attacks occurred in the victim’s home.[25]

Prior to the passage of the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act (DVPP Act) in 2010, legislation on violence against women and girls in Bangladesh failed to adequately address domestic violence. The DVPP Act was an important step forward in broadening the definition of domestic violence against women and children to include physical, psychological, sexual, and economic abuse.[26] Additionally, the DVPP Act was the first law to address the need for protections for victims, including granting magistrates the power to issue compensation orders, child custody, restraining orders, and provisions for safe shelter.[27] Notably, however, domestic violence under the act is limited to those in a “family relationship,” interpreted to mean relations by marriage or kin, thus excluding people in intimate partner relationships outside of marriage. This discriminatory exclusion could, ironically, deter people in an abusive marital relationship from seeking divorce since it would negate the applicability of protections.[28]

The DVPP Act also created an enforcement officer (EO) position under the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs for each upazila (sub-district). The officer’s responsibilities include aiding the victim in making an application to the court for protection orders, accessing legal aid under the Legal Aid Act 2000, and referring the victim to a safe shelter if necessary.[29] However enforcement officers are often severely overburdened and underequipped. While single-handedly responsible for the implementation of the DVPP Act at the sub-district level, they have concurrent duties with the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and are often assigned to more than one upazila at a time. A women’s rights lawyer from Naripokkho explained that the enforcement officers “don’t understand the procedures. Also, they are from the Ministry of Women’s affairs and don’t want to be bothered with this [additional work]. There is a shortage of officers, they are not equipped, and they don’t have resources.”[30]

Cases filed under the DVPP Act are considered compoundable, meaning they can be settled out of court. Given the stigma and potential consequences of bringing their husband or in-laws to court without viable alternatives such as safe shelter or other protection services, the option of outside settlement can be an attractive option for some victims. However, the availability of this option can be used to pressure victims to settle—and accept an outcome that does not adequately recognize their rights—even when they would prefer a court adjudication. A 2015 program evaluation of implementation of the DVPP Act found that there was a “tendency in the majority of cases for legal counselors to lean toward mediation and that women are often not told of all of their legal options.”[31]

Dissemination of information about the law also appears to be a problem. In an evaluation of implementation of the DVPP Act, Plan International and BNWLA found that as of November 2016, not only victims, “but many lawyers and even judges seem to be unaware of the law.”[32] Plan and BNWLA surveyed nine police stations in Bogra, Dinajpur, Chittagong, and Dhaka and found that only two of the stations had a register for domestic violence incidents and the necessary forms available.[33] In a 2019 interview with BNWLA, lawyers confirmed to us that this lack of information remains a problem.[34]

All of these factors combine to mean that domestic violence cases are still typically dealt with either through informal mediation or under previous legislation including the Penal Code, the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000, and the Dowry Prohibition Act, 2018, none of which include the range of protections for victims afforded by the DVPP Act.[35]

Laws Prohibiting Dowry

Dowries[36]—paid by the family of the bride to the family of the husband or the husband himself—remain common in Bangladesh despite being outlawed 40 years ago with the passage of the 1980 Dowry Prohibition Act and in additional provisions under the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan Daman Ain, 2000.[37] Ahead of Bangladesh’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in May 2018, the special rapporteur on freedom of religion noted that despite the Dowry Prohibition Act, “the tradition persisted and contributed to placing women in the humiliating position of being objects of bargaining.”[38]

According to Odhikar, between January 2001 and December 2019, there were over 5,800 incidents of dowry-related violence. In over half of those incidents, the woman was killed.[39] According to Ain o Salish Kendra, so far in 2020 there were 73 cases in which women or girls were physically abused over dowry-related issues, and 66 more cases that ended with the husband or his family killing her, at time of writing.[40]

Human Rights Watch documented four cases in which a woman’s husband—at times aided by his parents—attacked her with acid over a dowry dispute. Sahana, 58, said that after she was married at age 10, her husband would beat her constantly demanding she ask her parents for dowry. Her parents relented, giving him their own home. But it was not enough. Eventually he divorced her, but threw acid on her before leaving, she says, so that she could not find a new husband.[41]

In a 2015 report on child marriage in Bangladesh, Human Rights Watch found that disputes over dowries were often a trigger for abuse. In some cases, even after families paid dowries, they faced pressure to pay more.[42] A 2014 report on the visit of the special rapporteur on violence against women found that abuse over repeated demands for increased dowry following a marriage are common in Bangladesh:

Dowry demands are usually settled at the time of marriage; however, some men and their families continue to make dowry demands throughout the marriage. Women who are unable to satisfy those demands suffer threats of abandonment, beatings, cigarette burns, deprivation of food and medicine, acid attacks and, in some cases, death.[43]

In September 2018, parliament passed a new Dowry Prevention Act, 2018, with 11 additional provisions, some of which may actually lessen protections for women.[44] Section 2(b), excludes wedding “gifts” from the definition of a dowry, providing a loophole to make demands. Section 6 provides for punishment of up to five years’ imprisonment and a fine of up to 50,000 taka ($590) for making false allegations about demands for dowry, which can discourage women from coming forward if they have no evidence. Section 4 of the bill equally criminalizes both giving and receiving of dowry which could serve as a deterrent to reporting cases, such as those documented in this report, in which a woman’s family is coerced into giving dowry through violence, threat of violence, or other forms of pressure.

In reality, those facing pressure to give dowry are already very unlikely to bring the crime to the police. According to a 2016 Justice Audit survey of over 104 million people, when asked what their first advice would be if someone is asked for dowry, the most frequent answer was to recommend that they solve it peacefully between themselves. Only about 12 percent said the complainant should go to the police.[45]

Child Marriage Restraint Act, 2017 (CMRA)

Bangladesh has the highest rate of child marriage involving girls under the age of 15 in the world—nearly 40 percent.[46] According to UNICEF’s most recent data on Bangladesh collected in 2014, more than half of girls are married before the age of 18.[47]

Bangladesh’s Child Marriage Restraint Act (CMRA), 2017, makes it a criminal offense to marry or facilitate the marriage of a girl under 18 or a man or boy under 21, but the law is rarely enforced. [48] In 2017, Bangladesh took a major step back in the fight to end child marriage when the government repealed and replaced the CMRA to permit girls under 18 with no specified minimum age to marry under undefined “special circumstances.”[49]

Research demonstrates a strong correlation between child marriage and domestic violence.[50] A 2015 Human Rights Watch report based on interviews with 59 Bangladeshi girls and young women who had married before the age of 18 found that physical, emotional, and verbal abuse was common.[51]

Some of the cases of domestic violence documented in this report were also cases of child marriage. When Nusrat, 34, was 13 she was forced to marry her half-brother. She told Human Rights Watch that he would beat her regularly over the 18 years she was married to him. When she was able to move to Dhaka in 2016 to protect herself and her children, he found her, threw acid in her face, and stabbed her in the head with a knife.[52]

Bangladesh authorities committed to developing a National Action Plan to Eliminate Child Marriage for 2015-2021 but that has not materialized despite being nearly at the end of the proposed timeline. The government also pledged to end all marriage before age 15 by 2021 and all marriage before age 18 by 2041, pledges that seem unlikely to be met in the absence of a plan.[53]

Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence Against Women

Initiated in 2000, the Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence Against Women (MSPVAW) is a jointly operated program by the governments of Bangladesh and Denmark under the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs with the vision of building “a society without violence against women and children by 2025.”[54] The program developed the National Action Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children (2013-2025) focused on legal protections, social awareness, advancement of women’s socioeconomic status, protection services, rehabilitation services, inter-sectoral cooperation, and community involvement.[55] This year the project enters its third and final phase of implementation.

The program includes a number of important measures and interventions, including the creation of nine One-Stop Crisis Centers in major hospitals;[56] a One-Stop Crisis Cell in each of the 67 districts in Bangladesh responsible for coordinating access to the Crisis Centers, connecting victims with services, and monitoring and following up on cases; a National Trauma Counseling Center in Dhaka; a 24-hour national helpline for violence against women and children; and a database compiling data from all of the above institutions.

The hotline, created in 2012, has so far received over 3.9 million calls, most for general information followed by legal assistance.[57] The fact that the hotline receives millions of calls from women in distress yet so few women and girls are referred to available services including safe shelter, legal aid, and counseling, as well as referral to police for protection measures and legal recourse, demonstrates a glaring gap between apparent need and availability of promised resources. Not only do promised government services need to be made available, but the government must do a better job of coordinating with existing NGOs to ensure women and girls can access immediate and long-term care and support.

II. Social Pressure Not to Report Abuse

Survivors interviewed for this report often said that their husbands or in-laws had physically and verbally abused them for months, or even years, before they were attacked with acid, but none of them had reported the violence to the police. Activists say that this is often the case because the women and/or their families consider domestic abuse to be a private a matter to be resolved within the family. As one women’s rights lawyer put it: “Society thinks domestic violence is silly violence, that it’s something that normally just happens in the family.” [58]

According to a 2015 survey by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and UNFPA, more than half of married women or girls questioned had been physically abused at some point by their partners, but 72 percent never told anyone. When asked why they didn’t tell anyone, nearly 40 percent said they didn’t think it was necessary.[59] In a 2016 Justice Audit survey of One-Stop Crisis Centers, case workers said that the main reasons clients do not file domestic violence cases is either out of embarrassment in the family and/or community or fear of retaliation by their husband or his family.[60]

The parents of Salma, 24, paid a dowry to her husband’s family of around 100,000 taka (US$1,176) in 2015. But in her married home, she says her father-in-law beat her repeatedly asking for more money. After a month, Salma went to stay with her parents to escape the abuse. But when villagers started gossiping about her broken marriage, her parents asked her to return to her in-laws. When she said she was being physically abused, they said, “You just need to endure.”[61] Her father refused to seek police assistance and, with nowhere else to go, Salma returned to her husband.

Then, on July 26, 2015, after another fight over dowry, her husband and his parents grabbed Salma and held her down. Her husband forced her mouth open and poured acid down her throat.[62] Neighbors came when they heard her screaming and the in-laws said she had tried to drink it to kill herself. Her husband took her to a nearby hospital but left her outside. She said the hospital refused to admit her without her husband’s signature. She went 72 hours without medical treatment and now she cannot taste or swallow correctly. She is fed only through a tube in her stomach.[63]

Shammi married Abir in 2004, when she was 17. By 2006, with Abir increasingly in debt, Shammi started work as a housecleaner to support the family and then took a job at a factory doing the same work as Abir. He first told her to stop working because she was “traveling outside too much.” The couple would often argue, and then Abir would beat Shammi. She heard he was even bragging to the neighbors saying, “I beat my wife every day and one day I will change her face so that she can’t show her face to anyone.”[64] Then, in February, 2016, Shammi says that one day when she returned home from work Abir told their daughter to go outside, then he attacked her. He held Shammi down on the bed and poured acid on her face, locked the door from outside, and ran away.[65] Shammi said that neither she, nor anyone else, had ever complained to police about the domestic abuse before the acid attack because, she said, “it is not a good idea to go to the police because it is a family matter.”[66]

Shammi’s belief that domestic violence stays within the family is common. When Justice Audit surveyed over 104 million people in Bangladesh asking what their advice would be if someone was slapped or pushed by their husband or in-laws, though not seriously injured, more than half said they would tell them to solve it peacefully between themselves while less than five percent said to go to the police. If the violence resulted in serious injury, nearly a third still said to solve it between themselves, another third said to bring the issue to the local chairman, and only about 12 percent recommended the police.[67]

Nusrat, 34, was 13 when she was forced to marry Rakib, her half-brother from her father’s previous marriage. He beat her often, but she did not report him to the authorities fearing social stigma and criticism from relatives. While Rakib was working in Saudi Arabia, Nusrat started working in garment factories in Dhaka. In 2010, when Rakib returned to live in Bangladesh, he told Nusrat to stop working and move home with him to Sirajgonj. But then he began hitting her again. Without access to proper support or legal advice, Nusrat decided not to report Rakib to the police, but she returned to Dhaka with her children. Three months later, in August 2016, she was in her room in Dhaka when she recognized his voice, speaking to the landlord on the first floor. “Where does Nazia’s mother live?” she heard him ask. When she opened the door, he lunged at her, throwing acid and stabbing her in the head with a knife five times.[68]

Many women and girls are unable to leave a violent home for fear of abandonment and economic destitution. Runa, 30, told Human Rights Watch that her husband comes home drunk and beats her constantly. She said that she wants to leave but is worried she would not be able to financially care for her children.[69]

A 2012 Human Rights Watch report found that women in Bangladesh described enduring months and sometimes years of domestic violence because they knew if they separated or divorced, they would face economic destitution.[70] In a study by Plan International and BNWLA on the implementation of the DVPP Act, interviews with enforcement officers showed that when a woman did take her husband to court, the frequent response was for her husband to seek divorce—a prospect that could be economically and socially debilitating for an impoverished woman in Bangladesh.[71]

Without independent access to financial support, housing, and social services, many women and girls must rely on their families for protection and have little real choice to decide for themselves whether to seek justice and services.

Before more women and girls will feel comfortable coming forward to seek help, the government must address several key gaps. Services, such as safe shelter, counseling, and legal aid need to be available; the justice system should function to support victims of gender-based violence with a functioning witness protection program, specially-trained police and court officials, and implementation of protection orders; and people across the country—female and male—need to know that gender-based violence is illegal and that help is available.

III. Lack of Services for Survivors of Gender-Based Violence

The government’s 2013-2025 National Action Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children drove the creation of some important services, but much remains to be done to implement the goals of the plan and make services accessible, activists say.[72] Without robust measures to protect victims and witnesses, and access to services, such as emergency shelters, financial support, long term housing, and legal assistance with child custody and divorce that would make it safe and feasible to leave a violent relationship, many women in Bangladesh determine that it is too dangerous to try to leave or seek justice.

Sadia, 28, was 16 when she married her husband under duress after he threatened her with violence. She said that during the 12 years that she was married, her husband would beat her regularly and poured chemicals in her eyes three times, each time temporarily blinding her. But she never felt safe reporting the violence because she did not trust the police to respond properly. She said she had no support and, with nowhere else to go, feared enraging her husband, which would place her and her daughter at further risk.[73]

Shortage of Safe Shelters

Many domestic abuse survivors literally have nowhere they can go to escape the violence because Bangladesh has too few shelter spaces. There are only 13 longer-term government shelters for women and girls in Bangladesh. These include seven Safe Custody Homes run by the Ministry of Social Welfare, two of which are in Dhaka division, and six shelters run by the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs where women can stay with up to two children under the age of 12 for up to six months.[74]

In addition, there are eight Victim Support Centers (VSC), which technically offer short-term shelter for up to five days, run in coordination between the Bangladesh police and NGOs.[75] But shelter services at VSCs are inconsistent and unreliable, and activists say that in reality they often don’t allow stays beyond one night in case of emergency.[76] Finally, there are an estimated 15 additional NGO-run shelters.[77] In total, therefore, there are a mere estimated 36 shelters in a country with over 80 million women and over 64 million children. But even these details are contested, making obvious how near impossible it would be for a woman or girl seeking urgent safety from a violent situation to access these critical services.[78]

Of those available, short term shelters only allow for a stay of up to a few days and most shelters have strict rules which exclude some women from being able to access them at all. For instance, women and girls require a court order to stay at one of the Safe Custody Homes and women with more than two children have to seek a court order to access the shelters under the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs. Some shelters don’t allow boy children and others, particularly those provided by NGOs, are only for particular types of abuse such as trafficking, for example.

One of the key responsibilities of the enforcement officer under the DVPP Act is to be able to refer victims to safe shelter. But Plan International and BNWLA reported that the officers said that there were few or no options for sheltering victims.[79]

One-Stop Crisis Centers

The government created nine One-Stop Crisis Centers (OCCs) under the Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence against Women, an important service meant to provide social service support, immediate medical assistance, psychosocial counseling, and coordination with the police and district legal aid committees.

However, none of the survivors interviewed for this report have come into contact with a One-Stop Crisis center. This is not unusual. In fact, a 2015 Bangladesh Bureau of Statistic survey found that less than half of women surveyed could name any place where they could report intimate partner violence, and of those only 0.3 percent knew of the One-Stop Crisis Centers.[80] When in 2016 the Justice Audit asked One-Stop Crisis Center case workers what changes would help them do their work more effectively and efficiently, the most common answer was to raise awareness.[81]

In a 2016 Justice Audit survey, respondents rarely recommended One-Stop Crisis Centers as a place to go after an assault. When asked what their first advice would be if someone was physically beaten by their husband or in laws, only 0.01 percent of respondents—men and women— recommended going to a One-Stop Crisis Center. This increased only to 0.10 percent if the injury was “more serious.”[82] According to women’s rights activists involved in their creation, the actual functioning of the centers varies and other service providers reported instances of crisis centers and cells being inoperative or shut down.[83]

The government has expanded the network of crisis centers, “but they are not following up on protocol,” Shireen Huq, director of Naripokkho, one of the country’s oldest women’s rights organizations, explained. [84] According to a 2016 survey by the Justice Audit, the primary way that a victim accesses crisis centers is through referrals by doctors, so effective coordination with hospitals is critical. But, according to Huq, such integration “within hospitals has hit bottlenecks.”[85] In Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), for example, the crisis center was originally set up to be connected to the emergency room. It was expected to coordinate services and support for women or girls when they first come to the hospital following assault “so that she doesn’t have to go from pillar to post,” Huq said. “But then, because it took time from design to implementation, they gave that space to a blood bank. So now emergency room people never think of it as their department.” [86]

Despite these gaps in implementation, data provided by the Multi-Sectoral Programme indicates that since their creation OCCs have assisted over 42,000 women or children, including over 28,000 victims of physical assault, almost 14,000 victims of sexual assault, and over 500 burn victims.[87]

Victim Support Centers

Another important element of the National Action Plan to combat violence against women was the creation of the Women Support and Investigation Division of the Dhaka Metropolitan Police. The division is made up of three main units: a quick response team with trained female police officers to respond to emergencies, an investigation unit dedicated solely to investigating women and child abuse cases in Dhaka, and eight Victim Support Centers (VSCs).

The support centers, in coordination with a network of ten civil society groups, provide emergency shelter for a maximum of five days, and coordinate health care, legal advice, psychological counseling, and access to rehabilitation programs. However, “police assume the victim support centers will ensure all the necessary protections for victims,” a women’s rights lawyer explained, “but they have limited resources and capacity.”[88] The Dhaka Metropolitan Police Victims Support Center has even published recommendations to improve its own capacity to reach and support victims, including increasing safe home facilities, but those are yet to be implemented.[89]

Lack of Legal Aid and Services

The judicial system can be confusing for most people, but for women and girls facing gender-based violence there are additional challenges. In Bangladesh, women seldom have proper access to information and legal counsel, leaving them particularly vulnerable to corruption and abuse.

Survivors of acid violence and domestic violence are entitled to apply for free legal aid, including remuneration for mediation or legal representation and general financial assistance from both the National Acid Control Fund (NACF) and/or the Legal Aid Fund under the Legal Aid Services Act, 2000. Additionally, The Legal Aid Service Rules 2014, which specifically list who is eligible for legal aid under the act, includes women and children who are victims of acid burns; impoverished women; and people with physical disabilities.[90] However, funds from the National Acid Control Fund are rarely distributed to acid survivors and legal aid to survivors of gender-based violence is infrequent.[91]

In a March 2018 report to the United Nations Human Rights Council ahead of Bangladesh’s Universal Periodic Review, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Committee expressed concern “about the lack of access to justice for women and that the Legal Aid Fund was largely inaccessible for them.”[92] According to the NLASO’s 2019-2020 annual report, legal aid was distributed to 6,550 women and 17,330 men—over 2.5 times more men than women.[93]

Lack of access to education compounds these barriers. In its concluding observations in the most recent report on Bangladesh’s compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the CEDAW Committee expressed concern “about the lack of access to justice for women, especially women and girls in marginalized and disadvantaged situations,” in part “due to their lack of awareness, legal illiteracy, [and] costly legal procedures.”[94] According to a 2018 Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics report, over 40 percent of girls drop out of school before secondary exams in 10th grade.[95]

Shabnam, 43, who was attacked in 2001 by her husband’s cousins in a land dispute, said that when she brought her case to court, the public prosecutor expected her to pay 500 taka (US$6) for an initial sitting, but she did not have the money and so she gave up. “I don’t know how to read or write so I didn’t understand why the 500 taka,” she said.[96] A lawyer from BNWLA told Human Rights Watch that accessing justice for women in Bangladesh is particularly difficult because they are both “financially dependent and they also have no information about their own rights.”[97]

Another compounding factor for women seeking legal recourse is that it is expected that men will handle legal affairs, meaning that to pursue legal remedy on their own, women have to overcome the stigma associated with women pursuing justice, especially if they are bringing a case against their husband or another male head-of-household.

Rubina and her mother Parveen, who were attacked in the middle of the night on October 2, 2017, believe that the perpetrator is from Rubina’s husband’s family. But they do not know what the police are doing to investigate because, Rubina said, “we don’t have any information because there is no man in our family who can follow up.”[98]

IV. How the Bangladesh Justice System Fails Women

If women and girls facing gender-based violence in Bangladesh are able to overcome stigma and lack of social and legal services to seek justice, they often face abuse and obstruction in the criminal justice system. Women and girls who are victims of violence, including acid attacks, face barriers in filing police complaints, disinterest or abusive behavior from prosecutors, delayed and lengthy trials, and a lack of victim and witness protection that leaves them at risk of further abuse by the perpetrator or their family members.

Women and girls face discrimination in the legal system ranging from implicit bias, such as that demonstrated by police and court officials who refuse to take a case seriously or believe a victim, to institutionalized bias, such as the application of section 155(4) of the Evidence Act 1872 which states that a witness can be discredited in the case of rape if the defendant shows that the victim was “of generally immoral character,” a provision that women’s rights advocates have long sought to repeal because it is discriminatory, vague, and encourages defense lawyers to denigrate the reputation of women if they pursue criminal charges.[99]

Of the over 42,843 women who, at time of writing, had sought help through the government’s One-Stop Crisis Centers, 11,288 filed legal cases. There has been a final judgment in only 1,527 of these cases—about 14 percent. Of those 1,527 cases, there were only 160 cases in which a penalty was imposed.[100] Keeping in mind that most victims of gender-based violence never report it and only about 2.3 percent of victims of domestic violence take any legal action, it is discouraging that of those who do seek help, and additionally seek legal remedy, there is only about a one percent likelihood that they will see legal remedy.[101]

Below, we discuss failures of the criminal justice system in dealing with cases of acid violence. Those same failures expand manifold in cases of other forms of gender-based violence where there may not be corroborating medical evidence, where there is less public pressure to enforce the laws, or where implementation of the law is weaker.

Police Corruption and Negligence, Failures in Investigation

When women or girls do go to the police after an assault, they frequently face obstruction from police officers.[102] This can range from disbelief, refusal to file reports, and corruption, to negligence towards investigations. Women rarely trust that the police will offer them protection or that they will uphold the rule of law. According to a 2015 survey by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and UNFPA, only 1.1% of women surveyed who said that they had experienced domestic violence said that they sought help from the police.[103]

Bias, Lack of Response

In its concluding observations in the most recent report on Bangladesh’s compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the CEDAW Committee found that “existing rules, policies and plans addressing gender-based violence against women are rarely implemented due to stereotypes and gender bias, and lack of gender sensitivity on the part of law enforcement officials.”[104]

In March 2016, Sadia started working to afford hospital care for their daughter who had developed jaundice. The next month, when she was about to collect her first paycheck, her husband and two other men doused her with nitric acid.[105] But when she went to the police, they responded with disbelief, just as she had feared. Even after losing her left eye and left ear, it was still difficult to convince the police to keep her husband in custody. Sadia says that the Officer in Charge (OIC) at Rupnagar Thana told her, “I don’t think he did it, so we’re letting him go.”[106] Eventually her husband admitted that he attacked her because she “is educated and if she gets a job she might leave [him].”[107] He still calls her from prison asking her to drop the case against him and promising to take her abroad to get proper treatment. “I’m afraid if he ever gets out, he will try to kill me,” Sadia said.[108]

Women’s rights lawyers say that Sadia’s experience with the police is common. As one lawyer from Naripokkho explained,

When women come to the police, first the police don’t believe her. They shame her. The case starts with non-belief.[109]

A lawyer from BNWLA said police are more likely to file cases when a lawyer from BNWLA accompanies the victim. Otherwise, if she “individually goes to the police, the police frequently have a negative attitude and don’t believe the victim. A lot of police have no knowledge of how to handle gender-based violence cases.”[110]

Negligence and Corruption

How police handle a complaint plays a significant role in whether survivors are able to ultimately obtain legal recourse. In a review of 25 judgments in acid cases, ASF found that “efficient handling of a case by police appeared to be one of the main reasons for prosecution’s success.”[111] Conversely, when a case was dropped, stayed, remained unresolved, or resulted in an acquittal “inefficiency or corruption of police evidently played a major role.”[112]

In order to pursue legal recourse, victims are often obliged to pay bribes.[113] In many cases, women told Human Rights Watch that police would require a bribe before filing a First Information Report, or simply refuse to file a case. Transparency International’s 2017 Household Survey of Corruption in Service Sectors found that 60 percent of respondents in Bangladesh had paid bribes to law enforcement.[114] While these problems are common to all Bangladeshis who might seek legal remedy through the criminal justice system, this financial barrier to justice creates a disproportionate burden for women in Bangladesh, who are often financially dependent on their male head-of-household and are less likely to have access to information about the legal process. BNWLA and Plan International found in their 2015 report on the implementation of the DVPP Act, that “police inertia as well as harassment and abuse of women are not unusual, along with having to pay bribes to register cases.”[115]

At times, this can present an insurmountable obstacle to survivors pursuing justice. For example, Papia, 40, was attacked by her husband with acid in 1998 after her family refused to pay 50,000 taka in dowry (US$592). In the end, her family ended up paying much more in bribes to police just to file a legal case. When she was assigned a public prosecutor, he too expected bribes. “I was too ill and had no money, so I withdrew my case,” she said.[116]

Knowing that bribes are frequently required also leads to a lack of trust in the police and deters reporting violence or threats of violence. In a heated dispute a week before Shaheen, 49, was attacked with acid by a neighbor over a financial dispute in 2015, the neighbor’s uncle, a local government leader, warned Shaheen, “this day will be your last.” But she didn’t go to the police because she didn’t trust them and feared that they would just ask for bribes. “Never go to the police,” she said. “They are bad creatures. Police are always asking for money every time we see them. They always just ask for money.”[117]

Some survivors reported that even as they were paying bribes to the police, they heard that the accused was paying more, influencing the investigation in their favor. Taslima was attacked with acid in April 2018 by a relative over an interpersonal dispute. She said that at first the police were cooperative; they filed a First Information Report and arrested the perpetrator. But then she heard from her relatives that the perpetrator’s family had bribed the police to change the charge sheet. The police then filed a new charge sheet naming a friend of Taslima as the accused and the perpetrator was released.

Taslima’s husband said that one day the Officer in Charge from Ramna police called him and Taslima’s brother to Hazaribagh thana and told them to give up because “their case will be destroyed.” Even though Taslima was attacked in public in broad daylight, the family has given up on seeing any justice. Taslima’s husband said, “I want to see the perpetrators prosecuted, but I don’t see any way forward.”[118]

|

Nazmun's Case Nazmun, 23, ultimately did get to file a case and bring it to court, but her story shows the extreme and exceptional efforts necessary to secure a police response. In 2011, when Nazmun was about 17, her neighbor, who was in his mid-20s, started stalking her. He proposed marriage, and although she initially refused, her parents forced her to marry him.[119] The families agreed that she would continue school, but as soon as they were married her husband forbade her to go and tore up all her books.[120] “During the day he would pretend to be nice,” she said, “but at night he would beat me and fight with me over attending school.”[121] Nazmun continued attending school. The violence escalated, Nazmun said, and “one night he tried to strangle me.” A week later, when she was with her parents recovering from a fever, her husband came to see her. Nazmun says she warned her mother that she felt unsafe because he was acting strangely but her mother did not believe her. Unable to stay alert with a high fever, she eventually fell asleep. As she lay asleep, he poured acid on her. She woke up with a shock and saw him trying to run away. She felt her skin burning. “I saw my skin dripping down. Skin and muscles just falling off,” Nazmun said. Her parents rushed her to the hospital, and then her father went to the police station to file a case. But the police refused and told him to leave. He tried several times, but the police would refuse and kick him out. Nazmun’s family believed that the police were refusing to file the case because her husband had paid a bribe. Finally, as Nazmun was being transferred to Dhaka by ambulance, she and her father diverted the ambulance to the police station so they would see her horrific condition and would be forced to file a complaint. On hearing of the public pressure, a senior officer came to the station himself and took their information and started overseeing the investigation. Nazmun’s husband was finally arrested in 2012 but as of July 2017 when Nazmun was interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the trial was adjourned, awaiting appearance by three witnesses. |

Lawyers from Naripokkho said that police intransigence is common. When a woman is assaulted and comes to the police to report the abuse “they don’t help her, they delay in every way,” one lawyer said. She explained that often when a woman or girl reports an assault to the police she will have to share the story over and over again with multiple officers, often experiencing re-traumatization, “after which finally they decide, ok, we will file the case.”[122]

Failure to Investigate

One of the most common reasons acid violence cases lead to acquittal or remain in open investigation for years on end is a lack of sufficient evidence. In a 2016 Justice Audit survey, 62 percent of public prosecutors, 52 percent of magistrates, and 41 percent of judges said that poor investigations were the most frustrating part of the criminal justice system in Bangladesh.[123] This finding applies especially to cases of gender-based violence. In a 2015 study by BRAC University on the low rate of conviction in criminal cases of violence against women, insufficient evidence and weak police investigations were cited as one of the key reasons for low convictions rates.[124] As one lawyer from BNWLA said simply: “Investigations are the main problem. Police don’t communicate with the witnesses.”[125]

Section 11 of the Acid Offense Prevention Act directs all investigations of acid cases to be completed within 30 days of receiving a complaint, but most victims reported delays. Courts are expected to oversee the progress of acid cases. If the court finds negligence on the part of the investigating officer, a judge is authorized to replace or act against the investigating officer.[126] However, in none of the cases investigated by Human Rights Watch did this ever happen. In Nazmun’s case, officers were reprimanded for refusing to file a report but ultimately were not penalized.