“Will I Get My Dues … Before I Die?”

Harm to Women from Bangladesh’s Discriminatory Laws on Marriage, Separation, and Divorce

Glossary

|

Dowry |

In practice, payments, gifts, or other property from the bride and her family to the groom and his family at the time of a wedding and during marriage. The practice is illegal yet widespread. |

|

Kabin-nama, Nikahnama |

A marriage contract in Muslim law. The Bangladesh government has a standard format for such contracts. |

|

Mahr, Dower |

A property right that accrues to a Muslim wife at the time of marriage, part or all of which may be payable on demand and part on dissolution of marriage. It is paid by the husband or his family, and can take the form of money or property. |

|

Female-headed households |

A household headed by a woman where there is no adult male. In using this term Human Rights Watch does not imply that all households where there is an adult male are in fact male-headed. |

|

Kazi |

A licensed official who registers Muslim marriages and divorces. |

|

Khula |

A form of divorce through mutual consent for Muslims. Many scholars say that this is initiated by the wife and is available to her as an option only if she pays consideration to her husband (usually foregoing mahr). |

|

Talaq |

Unilateral, no-fault divorce, a power given to men under Muslim personal law. |

Summary

Shefali S., a Muslim, lived with her husband and in-laws. She worked in the family’s fields and did all the household work. When she was pregnant with their first baby, she learned of her husband’s plan to remarry and confronted him. He kicked her, and made her stand naked throughout a cold winter night as punishment. On one occasion he beat her to the point of unconsciousness. Eventually he abandoned her and remarried. Shefali continued to live with her in-laws and endure their beatings because her parents were too poor to support her and she felt she had no hope of securing maintenance.

Namrata N., a Hindu, gave her life savings to her husband to start a business. He misused the money, turned violent when she challenged him and demanded that it be returned, and eventually tricked her into drinking acid. “It felt like my mouth and insides were on fire,” she told us. He fled, and she is now dependent on a feeding tube. Namrata wants to divorce her husband but Hindu personal laws do not allow her to.

Joya J., a Christian, said she did household work from 5:30am every day. If she took a break even to play with her little daughter, her mother-in-law got angry. Often she had no time to bathe, and if she dozed off after lunch, her mother-in-law would get angry and insult her. Joya’s husband also occasionally beat and verbally abused her. Unable to bear the abuse, Joya escaped from her marital home several times, seeking refuge with a church and with her parents. Both the church and her parents forced her to return to her husband’s home. The abuse continued so Joya, with nowhere else to go and no money for housing, hid on a family friend’s verandah and in her bathroom. Her husband and in-laws spread rumors that she had run away with a man.

Shefali, Namrata, and Joya suffered the injustices of Bangladesh’s discriminatory personal laws and its consequences in different ways. Each of them contributed, financially or otherwise, to their marital homes. But Bangladesh’s laws do not recognize a wife’s contributions to the marital home and fail to give her equal right to marital property during marriage and at the time of dissolution. None of them was aware of any social assistance program or how to access it.

Bangladesh’s personal laws governing marriage, separation, and divorce overtly discriminate against women. Setting out separate rules for Muslims, Hindus, and Christians, many of these laws were codified decades (and in some cases more than a century) ago, and grant men greater powers than women in marriage and accessing divorce. The few economic entitlements for women recognized by these laws, namely maintenance and mahr (contractual amounts under Muslim marriage contracts), are often meager and difficult to secure.

As a result, rather than offer protection, Bangladesh’s personal laws often trap women in abusive marriages or propel many of them into poverty when marriages fall apart. In many cases these laws directly contribute to homelessness, hunger, and ill health for divorced or separated women and their dependents.

This report is based on interviews with 255 people in 2011, including 120 women who have experienced the shortcomings of Bangladesh’s personal laws, as well as lawyers, experts, government officials, and former judges. It finds that these laws discriminate against women during marriage, separation, and divorce, and exacerbate women’s economic inequality.

It also finds that family courts, where women can claim their minimal rights related to marriage, are often so plagued by delays, dysfunction and burdensome procedures that women wait months or years for any result. The report finds that there are significant barriers to and shortcomings in Bangladesh’s social assistance programs, which are failing to reach many women in extreme economic hardship after separation or divorce.

In Bangladesh, over 55 percent of girls and women over 10 years old are married. For many in the country, marriage offers economic security. But it might also result in financial hardship due to social pressure to leave jobs after getting married, the double burden of household work and reduced ability to participate in paid work, and a lack of control over income and savings. About 330,000 women in Bangladesh are divorced, according to government data, and an unknown number live separated from husbands.

The United Nations country team in Bangladesh has identified “marital instability” as a key cause of poverty and “ultra and extreme” poverty among female-headed households. The Bangladesh Planning Commission has said that women are more susceptible to becoming poor after losing a male earning family member due to abandonment or divorce.

Married women make contributions in many forms to family homes, businesses, fields and other assets, providing vastly more unpaid household and care giving labor than men. All married women whom Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report said they bore almost sole responsibility for household work, including cooking, cleaning, washing, grazing livestock, and fetching water. Many said they contributed significantly to their households at the time of, or during, marriage by selling jewelry, or relinquishing earnings or savings to their husbands. These contributions helped to buy property in the husband’s name, further his education, establish businesses, or help him get occupational or business licenses or permits. Almost all women said they gave their husband or in-laws a dowry.

Yet despite these myriad contributions, all but a handful of the women we interviewed were unable to exercise control over their income and marital property. Nor were they able to recoup anything or have their economic value recognized when their marriages ended.

“The suffering that women go through only Allah knows,” one Muslim woman, who struggled to afford housing and food after her husband left her, told Human Rights Watch. “I wish Allah could make us men not women.”

After decades of inertia, there is momentum for change in Bangladesh. In 2010, a law against domestic violence was introduced, which defines causing “economic loss” as an act of domestic violence and recognizes the right to live in the marital home. The law also empowers courts to provide for temporary maintenance to survivors of domestic violence. In 2012, the Law Commission of Bangladesh, supported by the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, completed nationwide research into reforms for Muslim, Hindu, and Christian personal laws. In May 2012, the cabinet approved a bill for optional registration of Hindu marriages. The Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs is also considering reforms to civil court procedures—especially on issuance of summons—that will improve family court efficiency. These small but important steps follow decades of pressure by women’s rights groups that have consistently demanded personal law and procedural reform.

Echoing their efforts, this report calls for personal law reform, procedural reform, better implementation of the limited protections currently available for women, and stronger state assistance for divorced or separated women, and women faced with domestic violence. Legal rights to a share of marital property on an equal basis with men and an entitlement to appropriate support from husbands or ex-husbands should be paired with access to social assistance where necessary; land distribution programs should be non-discriminatory so that female-headed households are not disadvantaged or excluded; and protection measures including access to shelters should be expanded.

The report notes strong opposition to reform, including from religious leaders averse to government involvement in “religious” affairs, or who argue that “religious” teachings offer no scope for reform. Law reforms related to family and religion is often contentious. But it is noteworthy that other countries with Muslim, Hindu, and Christian populations—including countries with Muslim majorities or countries that incorporate Sharia in their family laws, as Bangladesh does—have reformed personal laws to recognize greater rights for women. These reforms reflect diverse interpretations of “religious” teachings on marriage and its dissolution, as well as government recognition that states have an obligation to eliminate discrimination regardless of the personal law applied.

Discriminatory Personal Laws

Since its independence in 1971, the bulk of Bangladesh’s laws are applicable to all citizens without discrimination based on sex or religious belief, with one major anomaly: its personal laws. Some reforms, especially laws against domestic violence and acid attacks, have addressed family issues and apply across the religious spectrum. But personal laws on marriage, separation, and divorce, some dating to the 19th century, have remained largely frozen in time.

According to the 2001 census the large majority (89.7 percent) of Bangladesh is Muslim. Hindus constitute about 9.2 percent, Buddhists 0.7 percent, and Christians 0.3 percent of the population.

Muslims, Hindus, and Christians have separate laws on marriage, separation, and divorce. They are a mix of codified and uncodified (but officially recognized) laws, and are supplemented by authoritative decisions issued by the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and the High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh. Buddhists are governed by Hindu personal laws.

Bangladesh also has four civil laws broadly related to family matters that apply to members of all religions; the Special Marriage Act, the Child Marriage Restraint Act, the Guardian and Wards Act, and the Family Courts Ordinance. The Special Marriage Act applies only to those who renounce their religion and so is rarely used. The “civil” divorce law applies only to Christians and the few couples that marry under the civil marriage statute.

All three sets of personal laws discriminate against women with respect to marriage, divorce, separation, and maintenance, as explained below. They also fail to recognize marital property and its division on an equal basis after divorce or upon separation. This almost always benefits men and disadvantages women, unless the title to property happens to be in both the husband’s and wife’s names. This is rarely the case: a 2006 World Bank survey found that less than 10 percent of women surveyed had their names on any marital property documentation (rented or owned).

Muslims

Muslim personal laws are discriminatory in their embrace of polygamy for men, their unequal provisions on divorce, their limited rights to maintenance during marriage, and after divorce, their lack of maintenance beyond 90 days.

However, it is important to emphasize some positive aspects of Muslim personal law. It recognizes that the marriage is a contract. In fact a standard form marriage contract affords women the opportunity to negotiate better economic protection during marriage. But Human Rights Watch found that the 71 Muslim women whom we interviewed had little knowledge about the contract and the ways in which they could negotiate better terms.

Muslim personal law recognizes wives’ right to mahr pursuant to marriage contracts. But mahr amounts are often so small, especially for older women who have been married for a long time, that they fail to reflect the overall contributions a wife makes to marital assets. Moreover, even where higher mahr amounts were fixed for younger married women, Human Rights Watch found this right, more often than not, existed only on paper. Most women interviewed said their husbands defaulted on payments without sanction.

Polygamy forms a key basis for discrimination. The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance of 1961 aims at restricting polygamy by imposing procedural conditions. The law requires a husband to treat all his wives equitably and to seek the permission of a local arbitration council to take multiple wives, indicating to the council whether the previous wife or wives consented to the subsequent marriage. But of the 40 Muslim women Human Rights Watch interviewed in polygamous marriages, none said she had consented to polygamy or experienced an arbitration council review.

Experts said that local officials charged with convening arbitration councils are poorly trained, and that the government does not monitor compliance with polygamy authorization procedures. Moreover, while Muslim personal law calls for compulsory marriage registration, accessing and verifying records is difficult because marriage registrars maintain them manually and sometimes tamper with them. There are no centralized digital records. This, too, enables men to marry multiple times without authorization.

Muslim personal law also makes it far easier for men than for women to divorce. All Muslim men have an absolute right to unilaterally divorce at will (talaq, or no-fault divorce), whereas Muslim women may only do so if men “delegate” them this right in the marriage contract. While men’s right to divorce through talaq is supposed to be subject to arbitration council review, experts said this rarely happens.

Otherwise if a woman wants to divorce she must secure the consent of her husband. Men and women can divorce through mutual consent (mubara’t). Women may also seek a khula divorce—another form of divorce through mutual consent— but many experts say that this is available to women only if they pay consideration to their husbands (usually foregoing mahr). Alternatively, women can divorce through seeking court intervention under the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act of 1939, but only on specific grounds and via a lengthy process.

Muslim personal law recognizes wives’ right to maintenance during marriage, but upon divorce, maintenance is provided for only 90 days from the date of official notice, or if the wife was pregnant at the time of divorce, until the birth of the child. Family courts have sometimes denied maintenance during marriage where the wife has left the marital home and the husband claims that she has not been “dutiful,” “chaste,” or of “good character.” Lawyers did say that over time judges have been more willing to award maintenance during marriage if the reason wives left their marital homes was because of violence, dowry harassment, or abandonment by the husband.

Hindus

Hindu personal law, which is only minimally codified, has similar discriminatory elements. It allows Hindu men to marry any number of times, without any procedural preconditions. Divorce is not permitted for men or for women. Under a 1946 statute that partially codified Hindu personal law, Hindu women can formally apply in family courts to seek a separate residence and maintenance from their husbands, but only on limited grounds. Even those minimal rights are nullified if a court finds that the woman is “unchaste,” has converted to another religion, or fails to comply with a court decree ordering restitution of “conjugal rights.”

Hindu women applying for maintenance or a separate residence must prove they were married in the first place, a difficult task since Hindu marriages lack a formal registration system. In May 2012, the cabinet approved a bill for optional registration of Hindu marriages.

Christians

Christian personal law also discriminates against women. Divorce is allowed on limited grounds for both men and women, but the grounds are far more restrictive for women. Men can divorce if they allege their wife committed adultery. Wives, on the other hand, must prove adultery and one of a range of other acts. Such acts include: conversion to another religion, bigamy, rape, sodomy, bestiality, desertion for two years, or cruelty. Charges of adultery are particularly humiliating for women in Bangladesh’s conservative society.

Christian women are entitled to maintenance during marriage and alimony after divorce, but this is tied to their “chastity.”

Impact on Women and their Dependents

Bangladesh’s discriminatory personal laws harm women and their dependents during marriage and upon separation or divorce, contributing to violence against women and poverty in female-headed households.

Many women interviewed described being trapped in violent marriages because they feared they would end up homeless and unable to manage financially if they divorced or separated. Many Muslim women in polygamous marriages said their husbands beat them if they protested against remarriage, or that their husband and other wives abused them. Farida F., for example, said her husband and his other wife beat, starved, and verbally abused her, but she knew if she left him, she would face destitution. “I didn’t have anywhere to go,” she said, “so I just lived with whatever they did.”

Most divorced or separated women described severe economic hardship, including losing marital homes, living on the street, begging for food, working as live-in domestics to have a roof over their heads, pulling children from school to work, struggling with ill health, and lacking resources to deal with any of these problems. Aseema A., for example, said her husband threw her out of their home, and she got no maintenance or share of the marital property. She sent her 10-year-old daughter to work as a domestic worker, and Aseema lived and begged on the streets with her younger daughter until a landlord offered her housing and food in return for unpaid work in his fields. Mona M.’s husband abandoned her and took another wife, leaving her with no money to pay for health care after a miscarriage. She moved in with her widowed, impoverished mother.

Courtroom Battles

Family courts have primary responsibility for enforcing Bangladesh’s personal laws, but are plagued with procedural and administrative problems. Lawyers, former judges, and activists told Human Rights Watch that enforcement of court orders can take years, and is often riddled with problems around summons and notice procedures and processes for executing court decrees. Sitara S. told Human Rights Watch what motivated her to seek legal assistance to file a case in court after her husband divorced her. She said, “After he left me he didn’t give me anything. Not even one piece of cloth,” she said. “I am begging [for food] all the time. When I told him I’m going to court he laughed, saying, ‘Go to court. You will get nothing.’ When will I get anything from court?”

Other problems in family courts include inconsistent practices among judges related to evidence, unpredictable awards, failure to award interim maintenance, and lack of clear criteria for awarding maintenance.

While Bangladesh’s personal laws say judges can award maintenance, they are unclear about how to determine amounts and terms. For example, Muslim personal law gives no guidance for setting maintenance amounts even though it says that a husband should maintain his wife “adequately.” The personal law for Hindus says only that a court setting maintenance should “have regard to the social standing of the parties and the extent of the husband’s means.” For Christians and others who renounced their religion and married under the Special Marriage Act, a judge granting alimony may consider the wife’s “fortune,” her husband’s ability to pay, and the parties’ conduct. In practice, judges considered husband’s capacity to pay and the wife’s needs but there was little clarity on how these were assessed and men were able to argue against maintenance claims by asserting their wives were “unchaste,” not “dutiful,” or of bad “character.”

Other countries have much clearer statutory criteria for determining maintenance amounts. These often include consideration of the duration of the relationship, the impact of childcare and household responsibilities on the education and earning capacity of the dependent spouse, each spouse’s income, the health and age of the spouses, and contributions the dependent spouse made to realize the other’s career potential.

The summons and notice procedure required to get a husband to appear in family court for maintenance or mahr claims is also fraught with problems, including the failure of some judges to abide by legal timeframes and bribe-taking by officials who serve summons and notice. Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that these failings often lead to unreasonable delays in family court cases. In 2010 the Law Commission of Bangladesh recommended reforms to the summons and notice procedures, but the Bangladesh government has yet to amend these procedures.

Women seeking maintenance or mahr (available to Muslim women) in family court must first prove they are married. This can be a major obstacle for Hindu women who have no marriage registry, and for Muslims where registration practices are patchy and not digitized or centrally available. While evidentiary rules allow judges to consider oral evidence if documentary evidence is lacking, lawyers said this tends to happen only if women have children. A woman who cannot prove she has been legally married will fail in her claim. There is no legal protection for women who believe their marriage was legally recognized and cohabited, but later find that is not the case.

Even for women who succeed in maintenance or mahr claims, the battle is not over. To get husbands to pay, women must file for an execution decree and submit evidence of his assets or income, which they often lack. Human Rights Watch interviewed women who pursued execution decrees only to wait years for the court to act. A lawyer said one client had waited 18 years for a maintenance decree to be enforced, while a judge said another maintenance case filed in the 1980s was still in the execution stage in June 2011. A lawyer representing a woman who waited years for her maintenance order to be executed said her client had asked her: “Will I get my dues at least before I die?” In 2010 the Law Commission of Bangladesh recommended that claimants be allowed to file for execution of decrees at the same time as filing their initial claim to speed the process. However, the government has yet to amend the procedures.

A final battlefront for women seeking maintenance or mahr in family court is defending against frivolous, harassing counter-suits or criminal complaints lodged by husbands. This includes petitions by husbands for “restitution of conjugal rights,” whereby a court can order a wife to return to live with her husband. The practice of husbands bringing counter-suits for restitution of conjugal rights continues even though the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court has on several occasions held such orders unconstitutional (the court has also held otherwise). Experts also said that some husbands file criminal theft complaints if the wife leaves home with any of her belongings. Although husbands often drop the criminal charges, the complaints intimidate and harass women and their families.

Social Assistance

Winning a court case for maintenance or mahr would be an empty victory for the many divorced or separated women whose husbands are simply too poor to pay. For these women, access to state assistance is critical. Divorced and separated women, and women who want to escape domestic violence, need adequate access to shelters on an emergency basis, and to social assistance to tide them over in the immediate aftermath of separation until they are financially stable.

While Bangladesh has made important strides in relation to social safety net schemes, women still face problems of access and eligibility, and the administration of social assistance leaves much to be desired. The social assistance schemes also do not sufficiently meet the needs of women who are left more vulnerable because of intersecting reasons such as disability, old age, and ill-health. In 2011, the Planning Commission of Bangladesh resolved to develop a cohesive national strategy on social security to address shortcomings in existing social assistance programs.

Although the government runs seven shelters for women across the country, a Ministry of Women and Child Affairs official admitted to Human Rights Watch that more are needed. Homeless women and women who beg risk being detained in vagrant homes and subjected to criminal penalties for begging or living on the street.

Bangladesh also has an impressive array of social assistance programs for poor people, including a cash allowance program for widows and “husband-deserted” (separated or divorced) women. Under that program, such women can receive 300 takas (US$4) per month if they meet financial need criteria.

However, several factors hamper this assistance, including the fact that many eligible women are unaware of the program, women say the allowance is too small to meet basic needs, and disbursements are sometimes delayed. Family courts, where many eligible women turn for help, are not linked to such social assistance programs and are not equipped to supply information about the program.

Bangladesh also has a policy on the distribution of state-owned land (known as khas land) to landless rural households that can also benefit female-headed households. However, activists told Human Rights Watch that only those female-headed households that have an “able-bodied” son are eligible to receive land. The application of this discriminatory policy excludes female-headed households with only daughters, with no children, or with only sons with disabilities.

Bangladesh is party to international treaties—including those pertaining to the elimination of discrimination against women, to civil and political rights, and to economic social and cultural rights—that guarantee the right to equality during marriage and at its dissolution and the right to social security. UN bodies, charged with monitoring implementation of these treaties have specifically rejected the notion that women should not have equal rights to marital property because of social or religious expectations that husbands will support their wives, and have called for law reforms to make spousal maintenance more effective. Bangladesh has also undertaken to dramatically reduce poverty by 2015 pursuant to the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, yet as that deadline looms ever closer, too little is being done to address poverty driven by discriminatory personal laws.

The Bangladesh government has taken small but important steps toward meeting its international obligations by approving a bill for the optional registration of Hindu marriages and supporting the initiatives of the Law Commission to review personal law reforms. Moving ahead with these reforms is vital for Bangladesh to meet its commitments to promote gender equality and reduce poverty, and to alleviate the suffering of women in Bangladesh.

In order to take advantage of this momentum for change, the Bangladesh authorities should take measures outlined below.

Key Recommendations

Work toward comprehensive reform of Bangladesh’s laws on marriage, separation, divorce, and related matters, in consultation with experts and civil society groups working on women’s rights and representatives including those working with minority communities. Launch a participatory process involving all affected communities to enact civil laws that do not discriminate based on religion and gender. In the interim, amend personal laws to eliminate discriminatory aspects, and strengthen mechanisms for implementing laws.

To this end, authorities should:

- Reform maintenance laws to:

- Develop clear criteria to guide the discretion of family court judges when determining maintenance amounts. The criteria should include: the duration of the relationship; the impact of childcare and household responsibilities on the education and earning capacity of the dependent spouse (typically the wife); current and likely future income of each spouse; the dependent spouse’s capacity to support herself; the health and age of the spouses; the dependent spouse’s needs and standard of living; other means of support; and contributions made by the dependent spouse to realize the other’s career potential.

- Abolish any link between a wife’s entitlement to maintenance and her “obedience,” “chastity,” “marital duties,” or “good character.”

- Review all family court and appellate procedures and streamline them to minimize delays. Urgently instruct existing family courts that their power to issue interim orders should be used to grant interim maintenance until final orders are passed. Enhance the capacity of family courts to handle separation, divorce, maintenance, and mahr cases expeditiously and fairly. Take measures to decrease backlogs and delays, including by appointing more family court judges or decreasing judges’ case load of other civil matters, and reforming summons and decree execution procedures.

- Fully recognize the concept of marital property and allow for its division on an equal basis between spouses at the time of dissolution of marriage for all communities, recognizing financial and non-financial contributions made by women.

- Initiate a nationwide awareness campaign against domestic violence in a variety of media and in formats accessible to those with disabilities, emphasizing the rights to marital home, protection against economic loss, and temporary maintenance. Encourage women to seek remedies under the law against domestic violence.

- Make marriage registration compulsory for all religions. Create digital records that are accessible throughout the country as proof of marriage.

- Ensure access to divorce is on an equal basis for men and women.

- Raise nationwide awareness about the negative consequences of polygamy, including its linkage with domestic violence, and work toward abolishing it. Ensure that such information is available in a variety of media and in formats accessible to those with disabilities.

- Until polygamy is completely eliminated in practice, ensure that any law abolishing polygamy protects the rights of subsequent wives and their children, including to property, mahr, and maintenance. Until a law abolishing polygamy is passed, strictly enforce laws that constrain men’s ability to marry more than one wife and enhance the notice period and permission requirements with clear proof of financial status.

- Undertake broader dissemination of information on social assistance programs; make information available in a variety of media and in formats accessible to those with disabilities to improve women’s awareness of existing programs, eligibility criteria, and application procedures. Link existing social assistance programs to family courts.

For full recommendations, see Section VII.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted between March and October 2011, including six weeks of interviews in Bangladesh and secondary research between March 2011 and June 2012.

Interviews took place in Dhaka city and Madaripur, Gazipur, and Noakhali districts. We chose to focus on Dhaka because of its mix of religious communities and the large numbers of separated and divorced women who filed maintenance claims in family courts. We chose the other districts because they also represented a variety of communities and economic circumstances, including landless communities. Some interviewees described experiences with divorce or separation that occurred in other parts of Bangladesh.

A Human Rights Watch researcher interviewed 255 people. These included:

- Individual or small-group interviews with 71 Muslim, 45 Hindu, and 4 Christian women about their experiences with marriage, separation, and divorce.

- Individual or small-group interviews with 96 lawyers, activists, and researchers with expertise on divorce and separation.

- Individual or small-group interviews with five former family court judges (all of whom were sitting family court judges within the prior two years and handled marriage, separation, and divorce cases), five kazis or Muslim marriage registrars, five union parishad members, and nine government officials.

Individual women interviewees were identified with the assistance of local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) providing services to women and most interviews occurred in their private offices. Where women were interviewed in villages, the interviews were conducted either in their homes or in courtyards, with as much privacy as possible. All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways the information would be used. Each orally consented to be interviewed. Especially where women were recounting their personal experiences, they were told they could decline to answer questions or end the interview at any time. Interviews lasted between thirty minutes and three hours and were conducted in English or Bangla, depending on the interviewee’s preference. Interviews in Bangla were conducted with the help of a female interpreter. Care was taken to minimize the risk to women who were recounting experiences that could further traumatize them, and some women were referred to local organizations for legal services. Interviewees did not receive any material compensation, but were reimbursed the cost of public transport to and from the interview.

The names of all married, divorced, or separated women interviewed for this report have been substituted with pseudonyms in the interest of the privacy and security of the individuals concerned. In some cases other identifying information has been withheld upon request.

Human Rights Watch also conducted a review of relevant laws, policies, surveys, and reports from the Bangladesh government, the United Nations (UN), academics, NGOs, and other sources.

The scope of this report is limited to an analysis of the impacts on women of discriminatory personal laws with respect to divorce and separation in the three religions: Muslim, Hindu, and Christian. Buddhists are treated as falling within the purview of Hindu personal laws for the purpose of family matters. The report does not analyze all ways that Bangladesh’s personal laws are discriminatory, nor trace the history of how these laws developed or the politics surrounding their codification during the colonial era. These topics are covered in many other sources.

The report does not examine the customary laws and practices of indigenous communities in Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s family courts, which are a focus of this report, have yet to be set up in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, home to at least 11 indigenous communities.

Where women were forced to leave their marital homes and are living separately from their husbands, with or without any formal legal process for such separation, Human Rights Watch uses the terms separated or separation. Human Rights Watch also uses the terms abandoned or abandonment where husbands left wives behind without giving them any information about their whereabouts. But in cases of both separation and abandonment, the marriage still subsists in law.

I. Women’s Economic Status and the Implications of Marriage

She asked me, “My husband provides me a roof over my head and three meals a day. Can you guarantee that if I leave him?”

—Bashir-Al-Hossain, legal secretary, National Grassroots Disability Organization, Dhaka, March 30, 2011, recalling a question posed by a client experiencing domestic violence.

Overview

Women fare worse than men in Bangladesh on many economic indicators, from employment to property ownership to poverty. Marriage may be a source of economic security for women, but may also be an impediment to women’s employment and control over financial resources. This section provides background on women’s economic status generally and on the financial implications of marriage for women. Later sections describe the economic harm resulting from divorce and separation due to Bangladesh’s discriminatory personal laws.

Background on Women’s Economic Status

Women’s participation in the labor force is far lower than men’s in Bangladesh. A 2009 government survey (the latest available) found that about 87 percent of men and boys aged 15 and above are employed, compared to about 30 percent of women and girls aged 15 and above[1] and that “[f]emales, as compared with males, have [constitute]… higher proportions of unpaid family workers.”[2]

Even when women are employed for wages, they face wage discrimination, and there is a large earning gap between men and women.[3] Looking specifically into the wage gap in Bangladesh, the International Labour Organization found in 2008 that women earn an average of 21 percent per hour less than men.[4]

Women are also far less likely to own land and other property than men. Information from the 2008 agricultural census (the latest complete findings published) found that women owned only 2.95 percent of all farm holdings.[5] The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization reported in 2011 that “male-headed households” in Bangladesh had land holdings more than twice the size of land owned by female-headed households.[6]

Women are also disadvantaged in registering land ownership. Land registration offices are typically staffed by men, which poses problems for women in conservative communities.[7] The registration process is also time-consuming and bureaucratic, a particular challenge for women who have lower levels of education and literacy than men. Corruption in the land registration processes has also been repeatedly documented.[8]

The International Property Rights Index, which ranks countries based on their property regimes, gives Bangladesh low marks on women’s property rights. In 2011, Bangladesh ranked 81 out of 83 non-OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries based on women’s access to land, credit, non-land property, and inheritance practices. Only Chad and Zimbabwe ranked lower.[9]

Discriminatory inheritance laws and practices are partly to blame for women’s lesser property ownership. Muslims, Hindus, and Christians have separate laws that govern inheritance.[10] In general for Muslims, daughters inherit one-half of what their male counterparts inherit.[11] Hindu women can inherit only a life interest in property, and cannot dispose of inherited property.[12] Hindu women who are believed to be unable to bear sons cannot inherit at all.[13] Christian laws permit more equal inheritance, but in practice Christian women do not always inherit on an equal basis with men.[14]

Even to the limited degree women can inherit, there is social pressure to forego this right. Some families use what might be women’s future inheritance as dowry payments to husbands’ families at the time of marriage, later leaving women out of inheritance.[15] Some married women decline their inheritance in deference to brothers, who they hope will support them in the event of marital breakdown.[16]

Marriage and its Economic Implications

I was so young I didn’t even know what marriage meant when I got married…. Even if I get money [wages] I come home and give it to my husband. If I don’t give him the money he beats me…. We just have to live with it. We can come out and try to live separately but it is very difficult.

—Saloni S. (pseudonym), Hindu, Noakhali district, May 22, 2011

Most women in Bangladesh marry quite young; the minimum age of marriage for girls in Bangladesh is 18.[17] The government estimates that more than 55 percent of women and girls over 10 years old in Bangladesh are married.[18] More than 2 million girls between ages 15 and 19, and another 250,000 girls between ages 10 and 14, are married.[19]

For many women and girls, marriage offers economic security. But it can also bring economic harm through pressure to leave jobs and do unpaid work at home, and loss of control over income and savings. Married women make financial contributions—both direct and indirect—to family homes, businesses, and other assets. But as later sections show, it is nearly impossible to recoup those contributions if their marriages end.

Impact of Marriage on Women’s Paid Work and Control over Income and Savings

Marriage, and the social expectations that accompany it, diminish women’s participation in the labor force. Married women perform more household work than men. Those with children shoulder more of the child care responsibilities. These responsibilities limit women’s ability to work for wages. Women who marry young and cut short their education have a further impediment to employment.

The Planning Commission of Bangladesh has found that “women face social pressure for early marriage, leading to loss of education, employment opportunities, decision-making power, and leading to early childbirth.”[20] A 2006 study found that more than 60 percent of husbands surveyed reported that their wives had no independent source of income. More than three-quarters of wives surveyed said that they had no income-generating activity of their own.[21]

Some women told Human Rights Watch that their husbands and in-laws pressured them to quit their jobs after marriage. Rumana R. stopped working in a sweater factory after she married and had to move. Her husband and in-laws did not want her to work. She said:

I preferred my earlier life. I could eat whatever I wanted to eat, could buy myself things. After marriage I could only work in the house.[22]

Similarly, Noorjahan N.’s husband refused to let her work after they married. She was forced to quit her job as a kindergarten teacher.[23] The same thing happened to Ravina R., who quit her job at a nongovernmental organization when her husband refused to let her work. She had hoped to keep working for pay, but instead she cooked, cleaned, washed, and fetched water for her family.[24]

Among women who do work after marriage, many receive no pay. The 2007 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (latest complete findings published) found that about 14 percent of married women surveyed reported that they received no wages and another 4 percent reported receiving payment in kind only.[25]

Marriage can also diminish women’s control over their earnings and savings. In the 2007 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 12 percent of married women surveyed reported that their husbands decided how the wife’s income should be spent, 56 percent decided jointly with their husbands, and 31 percent decided independently.[26] However, a 2006 nongovernmental study found that 78 percent of married women respondents with an income said that they could not use it without consulting their husband.[27]

Women’s control over their income increased with education level and household wealth. In the 2007 Demographic and Health Survey, 42 percent of women surveyed with secondary or higher education said they independently decided how their income should be used compared to 26 percent of women who had no education. Similarly, women in the wealthiest quintile were more likely to make independent decisions regarding their income than those in the lowest quintile.[28]

Marriage can also impede women’s control over savings. A 2006 study found that among women who reported having independent savings, 90 percent said their husband was aware of the savings and 85 percent said that they could not exercise independent control over it.[29]

Women’s Contribution to Marital Households

She used to say: “I am like Durga [Hindu goddess]. I have ten hands. No one recognizes how much work I do in the house. I make all the food for everyone in the house but eat the least.”

—Maksuda Akhter, lawyer, Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, Dhaka, October 4, 2011, recalling what a client told her.

Married women make significant contributions in many forms to family assets, including homes, family businesses, and other property. Married men do as well, but unlike men, women have virtually no prospect of recouping their contributions or enjoying their benefits if their marriage ends.

Non-Financial Contributions

Married women in Bangladesh make many contributions to family property that enhance the property’s value and are vital to sustaining the family, yet are not in the form of monetary or property contributions. While commentators tend to refer to these contributions as “non-financial,” they clearly have economic value.

Married women spend far more time than men on unpaid household work. This reduces women’s capacity to undertake paid employment.[30] A 2007 study found that 57 percent of men and 55 percent of women surveyed estimated that women spent between 16 and 20 hours every day performing household work.[31] More than 40 percent of both men and women surveyed reported that men do no household work whatsoever.[32]

All married women interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they performed household work including cooking, cleaning, washing, grazing cows and goats, fetching water, and caring for children and elderly parents and in-laws. Joya J. described her everyday routine before she separated from her husband:

My day began at 5:30 [a.m.] I woke up and made ruti-bhaji for breakfast. If the breakfast was not served by 7:30 then my mother-in-law would start shouting at me. I soaked the clothes, served everyone breakfast, and then washed clothes…. Then I bathed my daughter and fed her. My daughter would want me to play with her but my mother-in-law would start screaming, “What’s going on? Who’s going to make lunch?”… I felt torn but would leave her [Joya’s daughter], cook, and wash vessels. Often I didn’t even have time for a bath. Soon after I fed my daughter I would make her sleep. And if I dozed off after lunch then my mother-in-law would get angry with me again. It was non-stop work.[33]

Many married women told Human Rights Watch that they worked without pay on family farms or in family businesses. For example, Mohima M. said she embroidered for her husband’s tailoring business, but was not paid.[34] Shefali S. did unpaid farm work as well as household work, saying:

I went to the fields and sowed seeds—paddy, wheat, sugarcane—and harvested the crop and also did all the work around the house—cleaning, cooking, bathing the children, and feeding them.[35]

Financial Contributions: Savings, Assets, and Dowry

Many women also make financial contributions to marital households, adding value to the family’s property. But even these direct financial contributions are virtually impossible for women to recoup upon divorce.

When Ravina R. got married, her in-laws’ home had only one room. She and her relatives paid for the construction of a tin shed on the property for the newlyweds, spending 350,000 taka (US $4,267). She said:

I gave them all my savings. Then my elder sister and uncle also gave money. They gave everything, they gave earrings, bangles, ring, furniture, showcase, steel almirah (cupboard), fan, sofa.[36]

Similarly, Rukshada R.’s father gave her some money, which she gave to her husband to purchase land in both their names. Her husband bought land, but put the title only in his name.[37]

In some cases married women said they gave up their earnings and personal assets, like jewelry, to advance their husbands’ careers or businesses. Haseena H. and her mother spent all their savings—of 350,000 takas (US$4,267)—to enable her husband to migrate to Italy for work. He later abandoned her.[38] Lawyer Farhana Afroz told Human Rights Watch how her client Leela L.’s father had given her 200,000 takas (US$2,438), which she gave her husband for his business. He started beating her, forcing her to leave with no share in the business.[39] One former family court judge said he heard a case where the claimant and her father had given up all their savings to put her husband through medical school. After graduating, her husband divorced her, leaving her and her family with no savings.[40]

Dowry payments constitute another form of direct financial contribution to family property, or in effect the husband’s or his family’s property. Most often the practice of dowry is where the bride or her family gives money or other property to the husband at the time of, and sometimes after, marriage.

Since 1980 demanding or taking dowry has been a punishable offense.[41] Nonetheless, scholars and women’s rights advocates say the practice of demanding dowry is widespread.[42] At least one study has found that it is on the rise.[43]

Almost all married women interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had paid dowry.[44] Some faced repeated demands for more dowry, which sometimes escalated to violence. For example, Asma A. fled her marital home after her husband threatened to burn her for failing to pay more dowry. She said:

He [Asma’s husband] wants to improve his business… [He] doesn’t have a trade license and needs money for it. He already took all my gold jewelry and sold it. He gets angry when I don’t bring the money, closes the door and kicks me, chokes me, and beats me till I have bruises on my arms. Now he threatens to burn me even though I am pregnant. He says that if my parents don’t give me money I should become a prostitute and bring him money, or [he] threatens to leave me. He says that he can easily get married again and get 200,000 takas (US$2,438) as dowry.[45]

Shehnaz S.’s husband also harassed her for dowry. She said:

At the time of marriage my mother and I paid 40,000 takas (US$488). Three months later he wanted another 35,000 takas (US$427). My mother pawned her gold jewelry and borrowed money and gave it to him. He used to demand this money for his grocery shop business.[46]

Ownership and Control of Marital Assets

Despite wives’ contributions to marital property, husbands typically own and control family assets, moveable and immoveable. The 2006 World Bank Gender Norms Survey in Bangladesh found that less than 10 percent of all women surveyed and less than 3 percent of younger women (ages 15 to 25) had their names on marital property (rented or owned).[47] A 2000 study by the International Food Policy Research Institute based on household surveys in 47 villages in three districts of Bangladesh found that “husbands consistently owned more assets than wives, both at present and at the time of marriage”[48] and “the mean value of a wife’s current assets is only a tiny fraction of total household wealth.”[49] While 70 percent of wives in the study owned jewelry, only 15 percent owned household durables.[50]

Lack of ownership and control over marital assets was a common theme among the women Human Rights Watch interviewed. Saloni S., for example, said:

We struggled a lot to build the house. I sold my earrings, worked outside—worked in the fields, grazed cows—whatever money I got I gave my husband. But after all this the house is in my husband’s name.[51]

Neera N. worked in a poultry farm and gave all her earnings to her husband. He bought land in his name only. She said:

I spilt my blood and toiled for days to save the money. But what do I have to show for it? Nothing.[52]

II. Laws Relating to Marriage, Divorce, and Separation

Bangladesh, despite its strong laws on some aspects of women’s rights such as domestic violence, maintains an antiquated and discriminatory set of laws on family matters, including marriage, divorce, and separation. For almost all aspects of marriage and dissolution of marriage, Bangladesh defers to the laws and rules—written and unwritten—applicable to religious communities. These personal laws are deeply discriminatory against women.

The Constitution says that the “state” shall not discriminate on the basis of sex and other grounds, and that “women shall have equal rights with men in all spheres of the state and of public life.”[53] It does not explicitly guarantee equality in the “private” or “family” sphere.

Bangladesh has passed laws that promote women’s and girls’ rights in the family or private sphere, and which apply to all religious communities. In 2010 it adopted a landmark law on domestic violence, and has long had laws against dowry, other forms of violence, and acid attacks.[54] Bangladesh should now act to establish laws that guarantee women and men equality in marriage and at its dissolution.

This section explores Bangladesh’s personal laws and how they regulate marriage, divorce, separation, and spousal maintenance. It also explains the absence of law on division of marital property upon divorce. Finally, it describes past and current legal reform efforts, from proposals to enact a uniform civil family code for all religions to efforts to reform existing personal laws incrementally.

Personal Laws

Marriage, divorce, separation, and economic rights at dissolution of marriage are governed almost exclusively by personal laws of Bangladesh.[55] According to the 2001 census, the large majority (89.7percent) of Bangladesh is Muslim. Hindus constitute about 9.2 percent, Buddhists 0.7 percent, and Christians 0.3 percent of the population.[56] No statistics are kept for persons who identify themselves as being of no religion.

Personal laws in Bangladesh are a mixture of codified and uncodified rules. Codification happened mostly during the colonial era, with some personal laws dating back to the 19th century.[57] After becoming an independent country in 1971, Bangladesh adopted all laws that were in force prior to its independence.[58] These codified and uncodified rules are subject to interpretation by the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court, and as such case law also becomes a source of law.

Apart from the personal laws, the civil laws that apply to all religious communities in the context of marriage or divorce are the Special Marriage Act of 1872, the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, the Family Courts Ordinance of 1985, and the Guardian and Wards Acts of 1890.[59]

The preamble to the Special Marriage Act of 1872 states that it is meant to apply to people who do not profess specified religions or for specified religious groups where marriages are of questionable legal validity.[60] Family law experts say that the Special Marriage Act is rarely used, and in practice the government requires couples to sign a declaration renouncing their faith to marry under the law, in effect making it a disincentive to use the law.[61] The Divorce Act of 1869, originally only for Christians, applies to marriages formalized under the Special Marriage Act.[62]

Chart: Key Elements of Muslim, Hindu, and Christian Personal Laws on Marriage

and its Dissolution

-- |

Muslim |

Hindus and Buddhists | Christian |

|

Key codified laws governing marriage and divorce |

Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961; Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939; Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act, 1974 |

Hindu Married Women’s Right to Separate Residence and Maintenance Act, 1946 |

Christian Marriage Act, 1872; Divorce Act, 1869 |

|

Marriage / registration |

Marriage contract and registration required. |

No provision for registration of marriages. |

Marriage registration required. |

|

Mahr or dower |

Marriage contract specifies mahr / dower. Mahr / dower may be paid wholly or partially at the time of marriage. |

No equivalent of dower for Hindus. |

No equivalent of dower for Christians. |

|

Dowry |

Illegal and not sanctioned by religion. |

Illegal. Dowry demands are historically traced to religion, though scholars argue that in practice it has little to do with religion. |

Illegal and not sanctioned by religion. |

|

Polygamy |

A man may have up to four wives with consent of the previous wife, and all wives should be treated equally. Official authorization needed. |

A man can have any number of wives. No provision for consent of previous wives / equal treatment. No procedural protections. |

Not allowed. |

|

Divorce |

Husband: no-fault divorce through renunciation available and procedurally regulated. Wife: no-fault divorce available only if agreed by husband in marriage contract. Otherwise divorce available through mutual consent (mubara’t and khula forms). If no divorce out of court, then women can seek divorce through court intervention on certain grounds. |

No provision for divorce. Wife can seek court decree for separate residence and maintenance. |

Husband and wife can seek divorce on limited grounds. Grounds are more restrictive for women. |

|

Maintenance during marriage |

Husband should maintain his wife. Maintenance is tied to chastity and wife being dutiful. |

Husband should maintain his wife. Maintenance is tied to chastity and wife being dutiful. |

Husband should maintain his wife. Maintenance is tied to chastity and wife being dutiful. |

|

Post-divorce or post-separation maintenance |

Divorced women cannot get maintenance except during a 90-day waiting period from notice of divorce or during pregnancy, if pregnant at the time of divorce. |

There is no divorce. Wives can seek a court decree for separate residence and maintenance on limited grounds. The rules on chastity and being dutiful apply. |

Wives can claim maintenance post-divorce. |

|

Marital property |

Separate property only. Marital property not recognized, regardless of contributions. |

Separate property only. Marital property not recognized, regardless of contributions. |

Separate property only. Marital property not recognized, regardless of contributions. |

|

Institutions involved |

Local arbitration councils, family courts, and appeals courts. |

Family courts and appeals courts. |

Family courts and appeals courts. In case of divorce, the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court has original jurisdiction. |

Muslim Personal Laws

The Sunni-Hanafi school of legal thought applies to the majority of Muslims in Bangladesh.[63] The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance of 1961 along with its rules codifies and amends some aspects of it.[64] Other laws that have a bearing on Muslim marriages and their dissolution are the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act of 1939 and the Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act of 1974.

Marriage Contracts and Registration

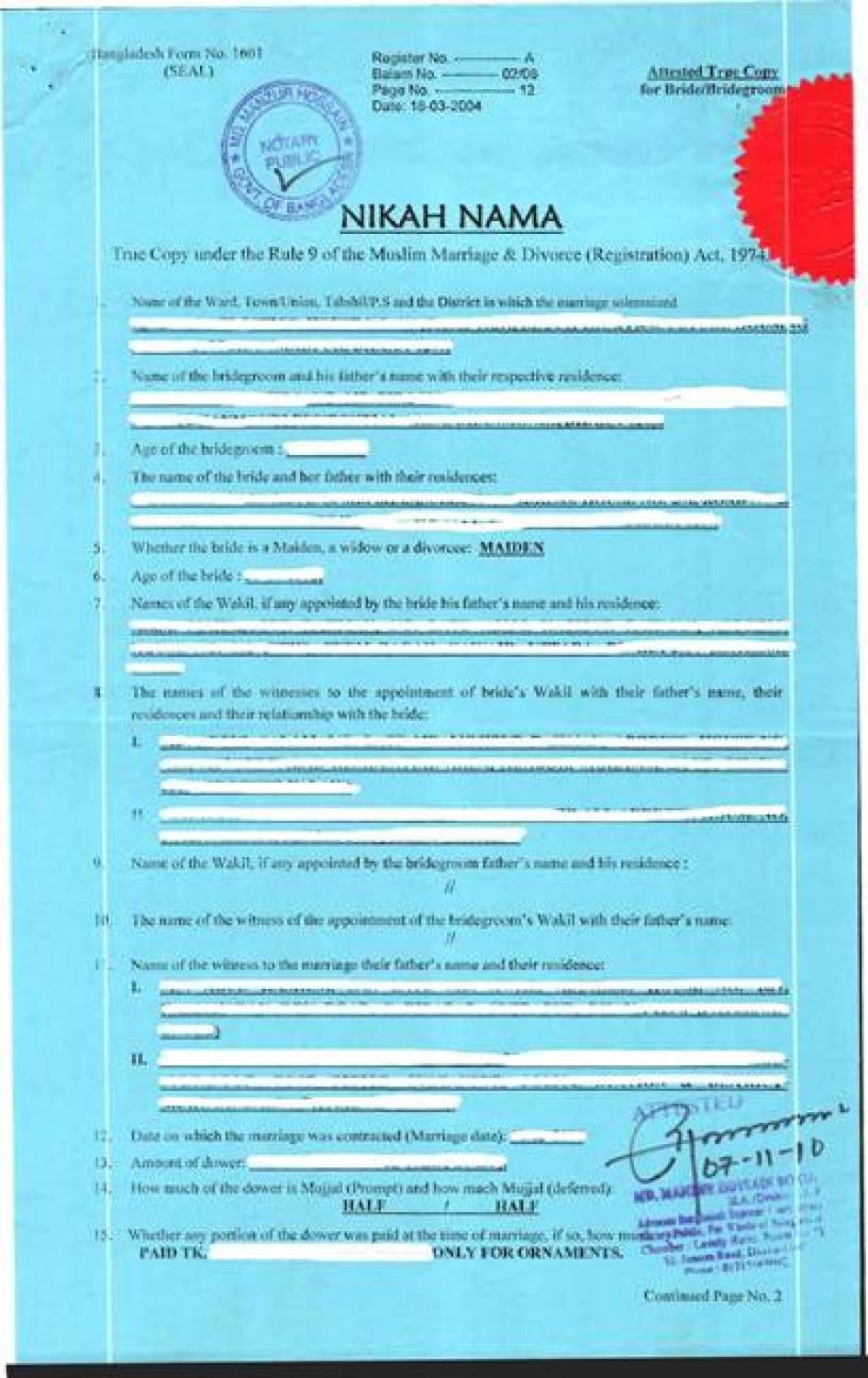

A Muslim marriage is formalized through a contract, known as a kabin-nama or nikahnama. The Bangladesh government has a standard kabin-nama that can be adapted.[65] The kabin-nama covers personal information, such as names, place of birth, marital status, and couples can specify the terms of marriage, such as the amount of mahr or maintenance.[66] The standard kabin-nama allows either party to introduce “special conditions,” including with respect to divorce and separation.[67] The standard contract is attached as Appendix I to this report.

The 71 Muslim women interviewed by Human Rights Watch had little knowledge or understanding of the significance of the kabin-nama, its clauses, and how they could negotiate the terms to protect their rights.[68]

Muslim marriages must be registered with a marriage registrar or kazi. The Bangladesh government appoints licensed kazis in accordance with the Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act of 1974.

Marriage registrars told Human Rights Watch that many couples fail to register their marriages, in part due to poor awareness and poverty.[69] For example, one Muslim widow told Human Rights Watch that she got her daughter married by asking the couple to place their hand on the Quran in her house because she was not able to pay for the marriage ceremony or organize money to meet the groom’s dowry demands, and the couple did not register the marriage.[70] Lawyers and activists who spoke to Human Rights Watch confirmed that this practice was not uncommon.[71]Kazis and activists said many couples marry by signing an affidavit before a notary, which has no legal validity.[72]

Mahr or Dower

Muslim marriage contracts stipulate that husbands must pay wives a certain amount of money or other property known as mahr or dower.[73] Some part is paid at the time of marriage, and the remaining later.

In theory, the right to receive mahr could secure significant property rights for women. However, many women interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had little or no role in fixing the mahr and several did not even know what the amount was.[74]

The manner in which mahr amounts are fixed is problematic. At times, mahr amounts are negligible, or become so over the course of a long marriage due to inflation and increased cost of living. Human Rights Watch interviewed women and a former family court judge about mahr amounts so small that they provided no economic security. In two cases women who sought mahr after decades of marriage could claim only a pittance: 101 takas (US$1.23) in one case,[75] and 2.5 takas (US$0.03) in another.[76] Human Rights Watch recorded other cases where mahr amounts were set as low as 51 takas (US$0.62), 500 takas (US$6.10), and 600 takas (US$7.31).[77] On other occasions, husbands had fixed high mahrwith no evidence that he had the means to pay, and did nothing to pay it when the marriage ended, rendering mahr an economic entitlement merely on paper.[78]

A wife is entitled to any outstanding mahr at the time of dissolution of marriage. However, women typically find it extremely difficult to enforce this claim.[79]

Polygamy

Two children—two wives—one drops out of school and becomes a rickshaw puller, and the other’s [child] finishes college.

—Maksuda Akhter, lawyer, Bangladesh Mahila Parishad, Dhaka, June 1, 2011

What permission? He [my husband] never said a word to me before he got married again. They get married again whenever they want to.

—Aseema A. (pseudonym), Muslim, Noakhali district, May 20, 2011

Polygamy among Muslim men in Bangladesh is common in many parts, but according to some sources is on the decline.[80] Human Rights Watch documented at least 40 cases of women in polygamous marriages and found that in all cases, polygamy had an adverse impact on women and their rights. Many said their husbands abandoned them after taking additional wives, leading to loss of housing and economic support.[81] Some also drew a link between polygamy and domestic violence, saying that their husbands beat them when they voiced opposition to taking another wife.[82] One activist recounted a case where the husband threw acid on his wife when she confronted him about remarrying.[83]

According to Shari’a a man can marry up to four wives, but the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance seeks to impose some procedural safeguards.[84] A man seeking to marry more than one wife is supposed to apply for permission to the chairperson of his local government structure, indicating whether his existing wife has consented to remarriage.[85] The chairperson should convene an arbitration council comprised of himself or herself and representatives chosen by the husband and his wife or wives. The council should only grant permission if it is “satisfied that the proposed marriage is necessary and just,”[86] and can impose conditions.[87] The law does not define what is “necessary and just” but the Muslim Family Laws Rules provide an illustrative list of circumstances when polygamy would be considered “necessary and just.” These are “sterility, physical infirmity, physical unfitness for the conjugal relation, willful avoidance of a decree for restitution of conjugal rights, or insanity, on the part of an existing wife.”[88] In theory, arbitration councils could impose additional conditions for remarriage to secure financial protections for women whose husbands seek to remarry.[89]

Men who fail to follow this procedure are required to pay the entire mahr due to his existing wife or wives.[90] The wife can also file a criminal complaint against the husband, with potential penalties of one year in prison or a fine up to 10,000 takas (US$122), and approach courts to dissolve the marriage.[91]

The bridegroom should disclose his marital status in the marriage contract, which marriage registrars should examine. The standard form of contract specifically asks “whether the bridegroom has any existing wife and, if so, whether he has secured the permission of the Arbitration Council…to contract another marriage.”[92] The kabin-nama also allows women to negotiate additional protections, which lawyers state could be used to secure greater protections in case of polygamy.[93] For example, a lawyer from Mymensingh district told Human Rights Watch that one client had introduced a right to a separate residence if the husband remarried.[94]

Muslim personal laws require that a husband treat all wives “equitably” (the term used in the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance) or “equally” (the term used by the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court in a decision on this requirement.)[95]

Legal procedures meant to regulate and limit polygamy are poorly enforced. Women, experts, and officials told Human Rights Watch that local bodies charged with handling polygamy applications did not discharge their functions, were poorly trained, and had little oversight. The legal protections on polygamy are also undermined by lax marriage registration procedures.

According to an activist from the Madaripur Legal Aid Association, many arbitration councils are inactive:

A lot of work needs to be done to activate the arbitration council….They need to serve notices, call parties to mediate when they receive applications for polygamous marriages, maintain records of their decisions….[96]

Of the 40 Muslim women in polygamous marriages interviewed by Human Rights Watch, each one said she learned from her husband, in-laws, other family members or friends of the other marriage, usually after the fact, and had no opportunity to oppose and prevent it even though she was against it. None of them had nominated a representative to the arbitration council, as is required under the law. For example, Saira S., whose husband remarried several times without seeking her permission, said:

When my son was one year old my husband got married again. I didn’t know about it then. But one day he brought the second wife home. She [the second wife] also did not know he was married. She stayed with us for three years and left. Then he went and brought another wife. When he went for another marriage [the fourth] I find out as they were making wedding arrangements because she [the fourth bride] lived in the same area.[97]

Rima R. also had no opportunity to protest her husband’s remarriage, learning of it after the fact in a phone call to her in-laws as they celebrated the marriage. She said her husband claimed the marriage was under duress from his mother, who threatened to commit suicide if he did not remarry. Rima said, “It’s okay if I commit suicide?”[98]

The arbitration councils are also at times a challenging environment for women opposing their husbands’ polygamy applications. Some officials and experts said the fact that women are rarely appointed to sit on arbitration councils makes them inhospitable to women.[99] One union parishad chairperson said:

It is important to have women members on the arbitration council so they can speak to the women freely and understand the problem. Sometimes women do not speak to us [men] when they come here.[100]

The local officials responsible for assembling arbitration councils receive little training and support from the government, which limits their effectiveness in enforcing the law on polygamy.[101] Moreover, local authorities and activists said that oversight of arbitration councils, which should be provided by the Ministry of Local Government, is often lacking. The Ministry has no system for supervising and collecting reports from local government officials regarding polygamy proceedings.[102]

Lax marriage registration procedures have undermined legal protections on polygamy. Bangladesh has a marriage registration system for Muslims, but even when it is used, it is not an effective mechanism to prevent men from remarrying without authorization. Non-registration does not invalidate the marriage. The registry system is not computerized, nor coordinated among districts, so men can easily register multiple marriages in a variety of districts.[103] Until recently, some men remarried multiple times in single districts by falsifying their name, but this practice should be deterred by a 2011 rule requiring applicants to show their voter identity card at the time of marriage.[104]

Divorce

Muslim personal law in Bangladesh permits several forms of divorce without resorting to court proceedings. The most common is talaq, or unilateral, no-fault divorce. Men have an absolute right to repudiate marriage through talaq, whereas a woman has a similar unilateral power of no-fault divorce only if her husband delegates this power to her in the marriage contract.[105]

In addition to the unilateral no-fault divorce powers, both the husband and wife can mutually agree to divorce (mubara’t). A less common form of divorce is khula, where a wife seeks the divorce and the husband must agree. Activists, lawyers, and kazis stated (and this is contested) that in this form of divorce, the wife must give some consideration, usually money or foregoing claims to mahr.[106]

An additional form of divorce which women can initiate was established by the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act of 1939, where women can seek divorce through court intervention. This act specifies the grounds on which women can seek divorce,[107] and according to legal experts, is not widely used because of the procedural hurdles and time taken in court.

The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance introduced procedural requirements for effecting no-fault talaq divorces, with a view to curtailing the unilateral exercise of such power by husbands. It requires that the party seeking divorce (usually the husband, but possibly a wife if permitted under the marriage contract) to give notice in writing to the spouse and the chairperson of his local government body. Within 30 days, the chairperson should constitute an arbitration council to try to reconcile the parties. If they do not reconcile, the divorce takes effect 90 days from the date the notice is received by the chairperson, or if the wife was pregnant, after birth.[108] Women, lawyers, and activists told Human Rights Watch that men seeking divorce often ignore or flout the procedures, back-dating the notices to avoid paying maintenance during the 90-day waiting period.[109]

Maintenance

Uncodified Muslim personal law requires that husbands “maintain” his wife or wives during marriage by providing food, shelter, and clothing. A wife is entitled to maintenance only if she is of “good character” and is a “dutiful” wife.[110] A wife can stipulate maintenance amounts and terms in the marriage contract.[111] None of the Muslim women who spoke to Human Rights Watch was aware of this possibility.[112] According to case law, if a husband fails to maintain his wife during marriage, she can assert a claim in family court for up to six years of “past-maintenance.”[113]

Upon divorce, however, Muslim women are entitled to maintenance only during the 90 days from notice of divorce until it is finalized, or if the woman was pregnant, until birth of the child.[114] Overturning a decision of the High Court Division, the Appellate Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court controversially held that the Hanafi school of Islamic law does not give Muslim women the right to post-divorce maintenance.[115] Many women’s rights activists and lawyers have criticized this decision, arguing that the Supreme Court’s interpretation was too technical and flawed.[116]

Hindu Personal Laws

Hindu personal laws governing marriage and separation are mostly based on the Dayabhaga school of Hindu law. Other than the Hindu Married Women’s Right to Separate Residence and Maintenance Act of 1946, these laws are uncodified.

Marriage and Polygamy

Hindu marriages are formalized through a religious ceremony, but do not require a marriage contract or registration.[117] Lawyers stated that many Hindu women were not aware of what constituted a valid Hindu ceremony in the eyes of law.[118] Some Hindu couples had married by placing their hands on the Bhagwad Gita without going through a religious ceremony.[119] In some cases, lawyers said that couples went to notaries and simply drew up an affidavit declaring that they were man and wife without going through the necessary religious ceremonies.[120]

Lack of registration is a barrier to proving marriage, including for women who seek maintenance when separated from their husbands. Lawyers and women’s rights activists have repeatedly called for a law requiring compulsory registration of Hindu marriages but that has been met with stiff resistance from the Hindu community. But the president of the Bangladesh Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian Unity Council told Human Rights Watch that despite public opposition, many Hindu leaders privately want a registration system. He said:

Hindu activists oppose marriage registration. But when they face personal problems—like sons going abroad—they come and ask for certificates from the Dhakeshwari mandir [temple]. Every week we are issuing four or five certificates for marriages conducted in the mandir.[121]

In May 2012, the Bangladesh cabinet approved a bill for optional registration of Hindu marriages.[122]

Hindu law permits polygamy for men, with no pre-conditions or limits on the number of wives. If a husband remarries, however, the wife can petition the family court for a separate residence and maintenance.[123]

Separation and Maintenance

Divorce is not permitted under Hindu personal law in Bangladesh. Hindu women can, however, seek a court decree for a separate residence and maintenance on limited grounds outlined in the Hindu Married Women’s Right to Separate Residence and Maintenance Act of 1946. The grounds are that the husband is suffering from a “loathsome disease not contracted from her,” treats her with “such cruelty” that it becomes “unsafe” or “undesirable” to live with him, the husband abandons her without her consent, remarries, converts to another religion, “keeps a concubine or habitually resides with a concubine,” and “other justifiable cause.”[124]

A Hindu woman is not entitled to maintenance if she is “unchaste,” converts to another religion, or fails to comply with a court decree for restitution of conjugal rights.”[125]

NAMRATA’S STORY[126]The impossibility of divorce under Hindu personal law means that even under the cruelest of circumstances, such as those endured by Namrata N., marriages cannot be dissolved. Namrata N., a Hindu woman in her twenties, married an artisan who wanted to start a workshop of his own, and asked Namrata for money. Namrata had saved about 200,000 takas (US$2,438) from working more than four years in a hospital, and gave her entire savings to him. Instead of using that money to start a business, he gave it to his parents. Namrata demanded that he return the money, and the relationship soured. Namrata’s husband started beating her. One night in 2009 when Namrata was ill, on the pretext of giving her water, her husband instead gave her acid. “He said he had brought me water to drink,” she said. “I drank some and felt like my mouth and insides were on fire.” Namrata’s husband fled after the attack, and continues to evade arrest. To this day, Namrata cannot eat or drink. She is fed through a bag with a tube inserted into her intestine. Namrata needs assistance to bathe or go to the bathroom, and her widowed mother had to quit her job to care for her. Namrata told Human Rights Watch that she wants not only justice, but also a divorce. “I want to see him in jail,” she said. “And when I get out of here [hospital] I will give him talaq [divorce]. If I can marry him, I can divorce him.” Namrata was unaware that despite this unthinkable cruelty, Hindu personal law would not, in fact, allow her to divorce. |

Christian Personal Laws

Christian marriage and divorce is governed by laws enacted in the late 19th century. Chief among these are the Christian Marriage Act of 1872 and the Divorce Act of 1869.

Marriage

Christian marriages are performed by a priest, a licensed minister of religion, or a marriage registrar in the presence of at least two witnesses.[127] They must be registered.[128] Polygamy is not permitted in Christian law. For Catholics, a marriage solemnized in church is governed by canonical laws also.

Divorce and Maintenance

Christians can divorce pursuant to the Divorce Act of 1869. Under this act, a husband can divorce his wife on the basis of adultery.[129] Wives, on the other hand, must prove adultery and one or several other acts. These include: conversion to another religion, bigamy, incest, rape, sodomy, bestiality, desertion for two years, or cruelty.[130]