Summary

Schools are complicit in [the] exclusion. There isn’t really a culture of accessibility institutionalized in the school because we [people with disabilities] have to make it work.

—Edward Ndopu, activist, Johannesburg, November 2014

I can’t imagine him at age 15 unable to write his name. He’s supposed to have [a] life, to be independent. That is why I fought for education for him. I hope one day he will be a doctor…. He is able to do [many] things.

—Maria Mashimbaye, mother of an 11-year-old boy with spina bifida, Johannesburg, October 2014

All children, including those with disabilities, have a right to free and compulsory primary education, and to secondary education and further education or training. All people with disabilities have the right to continue learning and to learn and progress on an equal basis with all people.

South Africa was one of the first countries to ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2007, and is a party to five key international human rights treaties and two African treaties protecting and guaranteeing children economic and social rights. Since 1996, the government has also introduced strong constitutional protections and legal and policy measures to safeguard every child’s right to education free from discrimination.

In 2015, the government declared it had reached universal enrollment in primary education and achieved the United Nations Millennium Development Goal on education, requiring it to ensure that all girls and boys were in school and had completed a full course of primary education by that year.

This report casts doubt on that assertion.

Building on two previous investigations carried out by Human Rights Watch in 2001 and 2004—Scared at School: Sexual Violence against Girls in South African Schools and Forgotten Schools: Right to Basic Education for Children on Farms in South Africa—the report finds that progress on paper for children with disabilities has not translated into equal opportunities or protections on the ground.

It questions whether the government of South Africa has prioritized children with disabilities’ access to a quality, inclusive education—as it committed to do 13 years ago in its “Education White Paper 6”—and highlights numerous forms of discrimination and obstacles that children with disabilities face in trying to access such education that fosters inclusion, not segregation or integration.

Moreover, evidence in this report suggests the government has not reached “universal” education because it has left over half a million children with disabilities out of school, and hundreds of thousands of children with disabilities, who are presently in school, behind.

Key Findings

Among this report’s key findings:

- Discrimination accessing education: children with disabilities continue to face discrimination when accessing all types of public schools. Schools often decide whether they are willing or able to accommodate students with particular disabilities or needs. In many cases, children with intellectual disabilities, multiple disabilities, and autism or fetal alcohol syndromes are particularly disadvantaged. In most cases, schools make the ultimate decision—often arbitrary and unchecked—as to who can enroll.

- Discrimination due to a lack of reasonable accommodation in school: many students in mainstream schools face discriminatory physical and attitudinal barriers they need to overcome in order to receive an education. Many students in special schools for children with sensory disabilities do not have access to the same subjects as children in mainstream schools, jeopardizing their access to a full curriculum.

- Discriminatory fees and expenses: children with disabilities who attend special schools pay school fees that children without disabilities do not, and many who attend mainstream schools are asked to pay for their own class assistants as a condition of staying in mainstream classes. Additionally, parents often pay burdensome transport and boarding costs if special schools are far from families and communities, and, in some cases, they must also pay for special food and diapers.

- Violence, abuse, and neglect in schools: students are exposed to violence and abuse in many of South Africa’s schools, but children with disabilities are more vulnerable to such unlawful and abusive practices.

- Lack of quality education: children with disabilities in many public schools receive low quality education in poor learning environments. They continue to be significantly affected by a lack of teacher training and awareness about inclusive education methodologies and the diversity of disabilities, a dearth of understanding and practical training about children’s needs according to their disabilities, and an absence of incentives for teachers to instruct children with disabilities.

- Lack of preparation for life after basic education: the consequences of a lack of inclusive quality learning are particularly visible when adolescents and young adults with disabilities leave school. While a small number of children with disabilities successfully pass the secondary school certificate, or matric, many adolescents and young adults with disabilities stay at home after finishing compulsory education; many lack basic life skills. Their progression into skills-based work, employment, or further education is affected by the type and quality of education available in the special schools they attend.

Segregation and lack of inclusion permeates all levels of South Africa’s education system and reflect fundamental breaches of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Barriers to inclusive education begin in the very early stages of children’s lives because children are classified according to their disabilities.

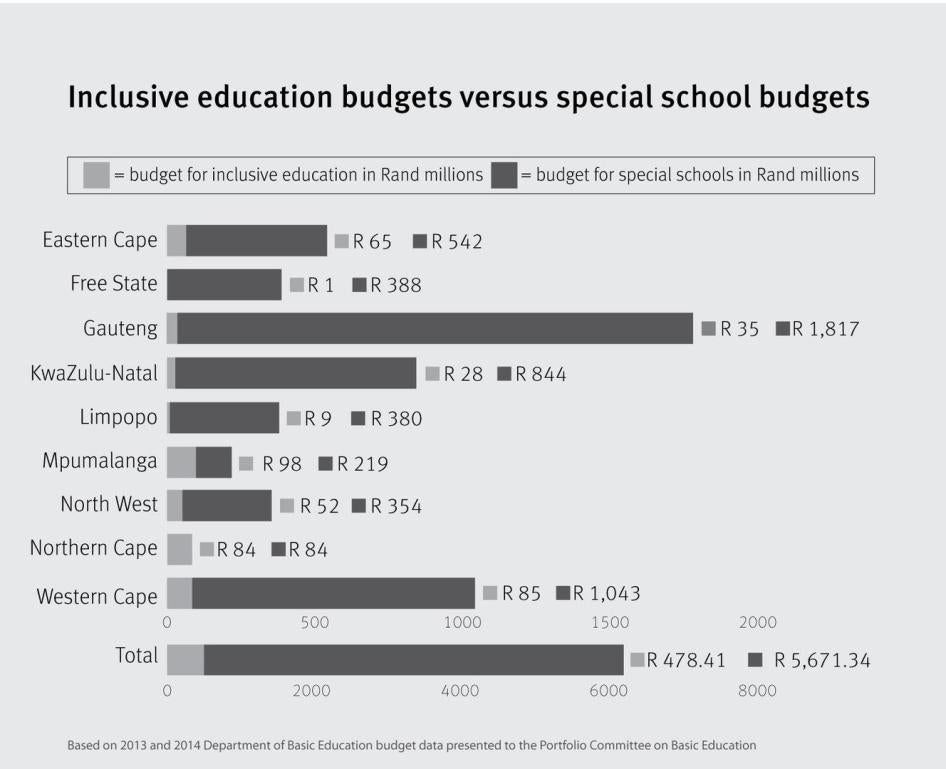

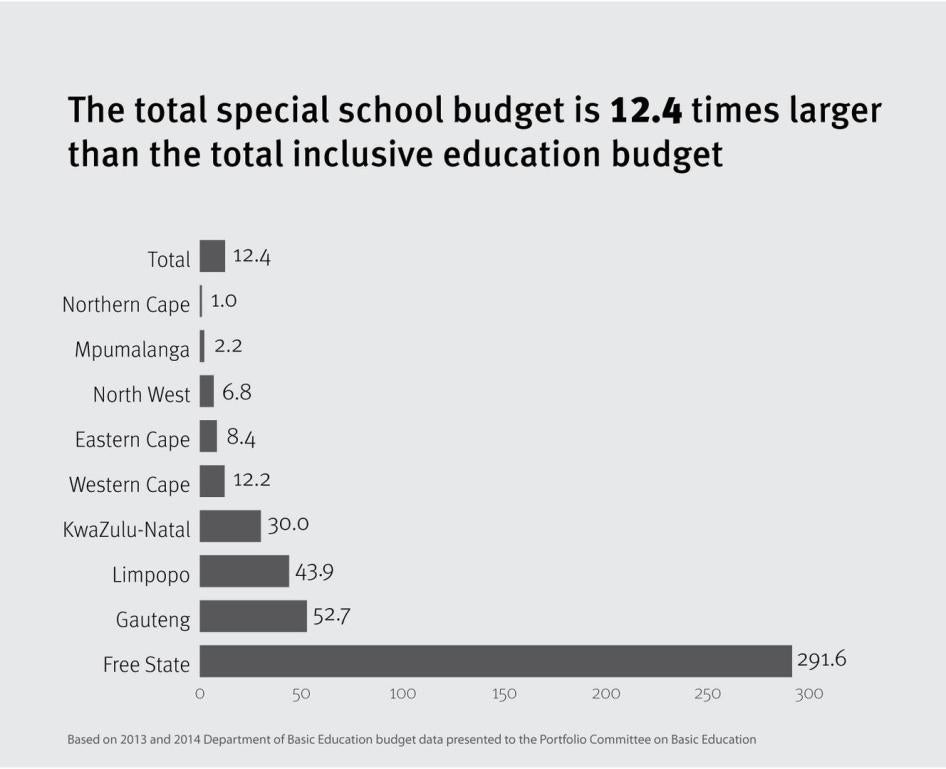

Several factors underpin these problems, including undercounting children with disabilities in governmental data, inadequate funding for inclusive education, and lack of adequate information and support services for parents, families, and children with disabilities. For example, Human Rights Watch found many parents faced uncertainty and navigated a complex system without information about their children’s disabilities, abilities, or the best type of education for them. In many cases, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) plug considerable gaps in the delivery of public services for children who have been left out of the education system.

Necessary Steps

Inclusive education focuses on ensuring the whole school environment is designed to foster inclusion, not segregation or integration. It benefits all children. Children with disabilities should be guaranteed equality in the entire process of their education, including by having meaningful choices and opportunities to be accommodated in mainstream schools if they choose, and to receive quality education on an equal basis with, and alongside, children without disabilities.

The government has accepted that progress has been slower than expected when it comes to implementing its policy on inclusive education—particularly for the poorest students with disabilities and children with multiple disabilities and high support needs—in large part because it has not been a key national priority, and provincial departments have not distinguished between “special needs education” and “inclusive education.”

The government should take immediate steps to turn its inclusive education policy commitments into legally binding obligations. These include ensuring:

- It honors a policy of inclusive education by making sure that children with disabilities have an equal opportunity and option to go to mainstream schools that are accessible, free of violence, and receive a quality education that addresses and accommodates their needs.

- All students with disabilities can complete basic education, at a minimum.

- All students with disabilities have equal opportunities to continue learning or enter vocational education and training.

- Adequate consultation with children and their families to determine a school placement that will maximize their academic and social development, consistent with the goal of full inclusion.

The government’s approach and shift towards a truly inclusive education system should also be both short and longer term.

Improving the quality of education in mainstream schools is a short-term imperative and a means to ensure all students benefit from education. In the short-term, the government should also improve the quality of education in special schools to ensure the current generation of children who want and need their services can benefit from education on an equal basis with students in mainstream schools.

The government should also immediately commence a transparent and frank process to review “Education White Paper 6” to ensure its education system is better able to respond to the needs of hundreds of thousands of children with disabilities.

In the medium to longer term, the government should ensure that students with disabilities can transition from special to mainstream and full-service schools. This should entail shifting investments now so that schools can accommodate children with disabilities, and teachers and support staff are adequately trained, empowered, and supported to teach children with disabilities in mainstream schools.

Creating new special schools for current and new generations of students with disabilities will not solve South Africa’s current challenges and may even exacerbate many violations of the right to education of children with disabilities outlined in this report. The government should now move beyond statements of commitment to real, inclusive implementation.

Key Recommendations

To the Government and National Assembly of South Africa

Guarantee Right to Inclusive Quality Education for Children and Adults with Disabilities

- Affirm commitments to guarantee the right to inclusive education for all children with disabilities;

- Require all public schools, as defined in the Schools Act, to ensure reasonable accommodation for all children with severe learning difficulties and multiple disabilities;

- Establish and define short-term goals and timeframes to ensure students with disabilities can transition from “special needs education” or special schools to inclusive mainstream schools;

- Amend the Schools Act to bring it fully in line with the country’s international obligations with the effect of explicitly making primary education in all public schools free and compulsory for all children, ensuring meaningful access to quality education for children with disabilities and enforcing the right to access Adult Basic Education and skills programs for people with disabilities who have not completed basic education;

- Collect and regularly publish lists of children with disabilities on waiting lists, those waiting to be referred to special schools, as well as out-of-school children with disabilities, in order to provide an accurate account of the status of enrollments;

- Ensure schools have taken all necessary steps to provide individual learning support and remedial education to leaners with disabilities who are lagging behind.

Comply with Existing National Laws and Political Commitments

- Deliver a government gazette, an official government communiqué, with compulsory school-going ages for children with disabilities, adapting it to accommodate students who enter school late, as well as reasonable accommodations;

- Publish Norms and Standards for funding of inclusive education to ensure public special schools can qualify as “no fee schools” and do not charge fees, and prohibit all public ordinary schools from imposing financial conditions on children with disabilities that children without disabilities would not incur;

- Finalize and publish the “National Learners Transport Policy,” guaranteeing inclusion and subsidized transportation for students with disabilities.

Adopt Stronger Policies and Laws on Inclusive Education

- Begin a transparent process to review “Education White Paper 6”—the government’s inclusive education policy—with a view to adopting a new policy on inclusive education to replace the existing policy;

- Translate “Education White Paper 6” into a comprehensive law binding national and provincial governments, ensuring it is in line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Increase Accountability in the Education System

- Invest necessary resources in improving data systems to ensure schools of all types account for numbers of children with disabilities in school, grade levels, progression and drop-outs;

- Urgently set up a centralized register of waiting lists and children waiting to be placed and improve data collection of out-of-school children in institutions or centers managed by the Department of Social Development. Ensure such lists are available to parents and civil society organizations upon request.

Allocate Resources and Safeguards to Guarantee Inclusive Education

- Deliver a national conditional grant to implement inclusive education goals and pay for non-personnel funding, including accessible infrastructure, assistive devices, and material resources to reasonably accommodate all children, among others;

- Develop an adequately resourced implementation plan to ensure all public ordinary schools accommodate children with high levels of support needs in line with the commitments made in “Education White Paper 6”;

- Mobilize inclusive education funding into mainstream and full-service schools to meet the milestones laid out in “Education White Paper 6,” and invest existing resources to more effectively promote inclusion and enhance quality in mainstream schools.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in October and November 2014 in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Northern Cape, and Western Cape provinces. Human Rights Watch selected these provinces to document disparities in access to education for students with disabilities in historically disadvantaged provinces, remote or rural provinces, as well as provinces with greater resources and greater provision of services for people with disabilities. We documented cases in townships and both urban and remote, rural settings.

Researchers conducted 135 interviews in person and by phone. Evidence used in this report is based on interviews with 70 parents on the experiences of 55 children with disabilities and 15 young adults with disabilities.

Disabilities included physical, sensory (blind, low-vision, deaf, or hard of hearing), intellectual disabilities, including cerebral palsy and Down Syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, and fetal alcohol syndrome disorders. Eight children had multiple disabilities. Nine children had epilepsy. Ten children and young adults were specifically referred to as “slow learners,” a term used to label persons with intellectual or learning disabilities.

Whenever possible, Human Rights Watch spoke directly with children and young adults, except where they had disabilities that impeded their ability to participate comfortably or they had not learned sign language. Seven separate interviews were conducted with children ranging from 9 to 17 years old. Sixteen young adults ranging from 18 to 30 years old were also interviewed, separately or with their parents.

Interviews took place in English, or were translated into English by members of organizations of persons with disabilities or other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). In each case, Human Rights Watch explained the purpose of the interview, how it would be used and distributed, and sought the participant’s permission to include their experiences and recommendations in this report.

Participants were told they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any question. Some parents received a small reimbursement for travel expenses if they traveled long and costly distances to meet researchers.

Human Rights Watch took great care to interview children, young adults, and their families in an appropriate and sensitive manner. Interviewees are identified by their real names, or first names in the case of children, except when they requested otherwise. Foreign national parents, concerned about the impact on their immigration status, requested anonymity.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 18 representatives of NGOs, including members of organizations of persons with disabilities, and education, human rights, and advocacy organizations and self-advocates; 10 experts and practitioners, including teachers, social workers, educational psychologists, doctors, occupational therapists, assistants, and caregivers who have direct experience with children with disabilities; 12 service providers ranging from NGOs providing an essential service to a social enterprise selling affordable wheelchairs to the government; as well as leading academics and journalists involved in education or disability rights. Some parents have a dual role as parents of children or young adults with disabilities and as former or current teachers, or education experts in NGOs, service providers, or schools.

Human Rights Watch visited four government special schools, two nongovernmental special schools, six formal and informal day care centers (or crèches) and one skills center for adults with intellectual disabilities. Interviews took place inside and outside schools with 14 school staff members and social workers from nongovernmental schools, government special and mainstream schools, care and stimulation centers, skills centers/protective workshops, and informal stimulation centers and crèches. We requested but were not granted permission to visit five additional special, or special boarding, schools. We also interviewed representatives of the National Professional Teachers Organization of South Africa. South Africa’s Democratic Teachers Union did not respond to numerous requests for an interview or comment.

Human Rights Watch interviewed six government officials at the National Department of Basic Education, and communicated by email and telephone with various provincial education officials. The Disability Rights Unit was in the process of moving from the now defunct Ministry of Women, Children and People with Disabilities to the Department of Social Development during the research. A senior representative of this Unit declined a meeting with Human Rights Watch due to the transfer of this unit’s functions and the absence of internal protocols. We interviewed two commissioners at South Africa’s Human Rights Commission and consulted a number of international disability experts during research and writing.

We also reviewed case studies, National Assembly archives and briefings, government documents, statements and progress reports, government submissions to United Nations (UN) bodies, UN reports, NGO reports, academic articles, newspaper articles, and South African case law on the right to education, among others. Four NGOs shared data, case studies, and evaluations based on their programs and outreach activities with children with disabilities.

The exchange rate at the time of the research was approximately US$1 = R11 South African Rand; this rate has been used for conversions in the text, which have generally been rounded to the nearest dollar.

Glossary

Autism spectrum disorder: A lifelong, complex condition that occurs due to disordered brain growth, structure and development. Autism is believed to stem from a genetic predisposition triggered by environmental factors and affects four to five times more boys than girls. Since a person can manifest their autism in a vast number of ways, this condition is now often referred to as "Autism Spectrum Disorders."

Cerebral palsy: A condition that affects movement, posture, and coordination. These problems may be seen at or around birth and mean part of the brain is either not working properly or has not developed normally. This may be due to problems during the first weeks of development in the womb (such as an infection) or the result of a difficult or premature birth. Sometimes there is no obvious cause.

Developmental disability: An umbrella term that refers to any disability starting before the age of 22 and continuing indefinitely (likely lifelong). It limits one or more major life activities such as self-care, language, learning, mobility, self-direction, independent living, or economic self-sufficiency. While this includes intellectual disabilities such as Down Syndrome, it also includes conditions that do not necessarily have a cognitive impairment component, such as cerebral palsy, autism, epilepsy, and other seizure disorders.

Epilepsy: The most common neurological condition, impacting on the body’s nervous system, characterized by unusual electrical activity in the brain, causing unprovoked seizures and sudden, uncontrolled movements. Epilepsy, however, is not a psychological disorder, disease, or illness, and not all cases of epilepsy are lifelong. About 80 percent of people can effectively control their seizures with medication and a healthy lifestyle.

Fetal alcohol syndrome disorder: A group of conditions that can occur in a person whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. Fetal alcohol syndrome causes brain damage and growth problems. These effects can include physical problems, behavior and learning problems, or an intellectual disability. Often, a person with this disorder has a combination of these problems.

Intellectual disability: Characterized by significant limitations in intellectual functioning (reasoning, learning, problem solving) and adaptive behavior, covering a range of everyday social and practical skills. “Intellectual disability” forms a subset of “developmental disability,” but the boundaries are often blurred as many individuals fall into both categories to differing degrees and for different reasons.

Learning disability: Difficulties in learning specific skills, such as reading, language, or math. They affect people's ability to either interpret what they see and hear, or to link information. Children with learning disabilities may also have trouble paying attention and getting along with peers. Learning disabilities are not related to intelligence or educational opportunity.

Public school: South Africa’s Schools Act regulates public schools and lists three types: public ordinary schools, referred to as “mainstream schools” in the report, schools for students with special education needs, referred to as “special schools” in the report, and schools focused on music and the creative arts, among others. Public schools are not automatically free of charge. School-governing bodies and provincial governments have discretion to charge fees.

Severe and profound disability: A range of intellectual functioning extending from partial self-maintenance under close supervision and limited self-protection skills in a controlled environment, to limited self-care and requiring constant aid and supervision, to severely restricted sensory and motor functioning and requiring nursing care. Children with an intelligence quotient (IQ) of less than 35 are considered to be severely (IQ levels of 20-35) or profoundly (IQ levels of less than 20) intellectually disabled.

I. Overview: Inclusive Education

After the formal end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa’s government faced an urgent need to focus on the right to education of millions of children who had faced racism, exclusion, and discrimination accessing education, as well as children who had been subjected to an inferior quality education.[1] Children with disabilities were recognized as deserving particularly urgent attention.[2]

In the more than two decades since, the government has adopted steps to democratize education by guaranteeing an equal right to basic education in law, policy, and practice. Its constitution protects the right to a basic education,[3] and protects individuals from any discrimination, including on the grounds of race and disability.[4]

Schools Act, 1996

The 1996 Schools Act guides the government’s obligations related to basic education and stipulates the compulsory nature of basic education for all students aged 7 to 15. All children should be in school by 5 to 6 years old for grade R or pre-school.[5]

All public schools must admit students and “serve their educational requirements without unfairly discriminating in any way.”[6] All of South Africa’s nine provinces must also “ensure that there are enough school places so that every child who lives in his or her province can attend school.”[7] The government must undertake “all reasonable measures to ensure that the physical facilities at public schools are accessible to disabled persons.”[8]

When determining the admission of a learner with disabilities in a public school, education officials must take into account “the rights and wishes of learners with special education needs,”[9] as well as “the rights and wishes of the parents of such learner.”[10] The Schools Act also mandates that people with disabilities and experts on “special education needs of learners” be represented in governing bodies of ordinary public schools.[11]

Education White Paper 6, 2001

In 2001, the government gave itself 20 years to realize the right to inclusive education across the country, via a national policy known as “Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education.” [12]

At the time, the government estimated that more than 280,000 children and youth with disabilities were not in school, although most nongovernmental accounts put the number much higher.[13] It pledged to run awareness and enrollment campaigns to boost enrollment of out-of-school children and youth with disabilities of school-going age.[14]

The policy recognizes that “all children and youth can learn” and outlines key steps to ensure educational opportunities for students who experience or have experienced learning and development barriers, or who have dropped out of learning because of “the inability of the education and training system to accommodate their learning needs.”[15]

Although the white paper’s subtitle indicates a focus on “Special Needs Education,” the government’s policy made an attempt to move away from a special education and disability-focused model to a system that focused primarily on securing access to education for all children and respecting the importance of inclusion, thereby placing children in three types of “public ordinary schools,” according to their level of needs.

Contradictorily, the policy retained a strong focus on special needs education. To address parents’ and special needs practitioners’ concerns, the government clarified it would strengthen, rather than abolish, special schools for children needing more support.[16] The policy reinforced that:

Following the completion of our audit of special schools, we will develop investment plans to improve the quality of education across all of them… learners with severe disabilities will be accommodated in these vastly improved special schools, as part of an inclusive system.[17]

On paper, all government schools would offer children the same curriculum, while guaranteeing individual learners adequate assessments and support to ensure their “maximum participation in the education system as a whole.”[18] The three types of public schools are:

- Mainstream:[19] Meant to accommodate students with mild to moderate disabilities who require limited support, where the priority should focus on multi-level classroom instructions to respond to individual learner needs.[20] “Education White Paper 6” assumes that mainstream schools would be unable to provide for students requiring intense levels of support, who would need to be accommodated in special schools.[21] In 2013, 76,993 students with disabilities were registered in 3,884 mainstream schools.[22]

- Full-service: Introduced as a new form of ‘neighborhood’ mainstream schools, promoted as schools that would be adapted or built to accommodate children with disabilities and provide children with specialized services and attention in a mainstream environment. According to governmental policy, every district should have at least one full-service school. To cater to children with disabilities, these schools would receive support and expertise from special schools. In 2014, 793 schools were designated as full-service schools, with 24,724 “learners with special needs” enrolled.[23]

- Special schools: Meant to accommodate children with high levels of support and needs; many existed prior to the government adopting an inclusive education policy. According to the government’s policy, most of these schools would turn into “resource centers” to provide assistance and expertise to full-service schools.[24] In 2012, the government reported strengthening 295 special schools, converting 98 special schools into resource centers, and building 25 new special schools.[25] In 2014, 117,477 students, out of the 231,521[26] enrolled in public schools, were enrolled in 453 special schools.[27]

Within the special schools model, the government introduced a weighting system to respond to the diversity of disabilities in a classroom. The government introduced a method to calculate a maximum student-to-teacher ratio per classroom, weighted according to the type of disability.[28] To date, there is no equivalent weighting in mainstream schools. This means mainstream schools do not have applicable regulations to adjust their student-to-teacher ratio to accommodate children with disabilities’ needs in larger classrooms.[29]

In 2015, the Department of Basic Education admitted it faces very significant challenges in implementing an inclusive education system, particularly ensuring provincial governments comply with Education White Paper 6. In its progress report, released in May 2015, the Department of Basic Education advised the government to take “urgent and radical steps” to ensure it is able to reach some of the policy’s milestones by 2019.[30]

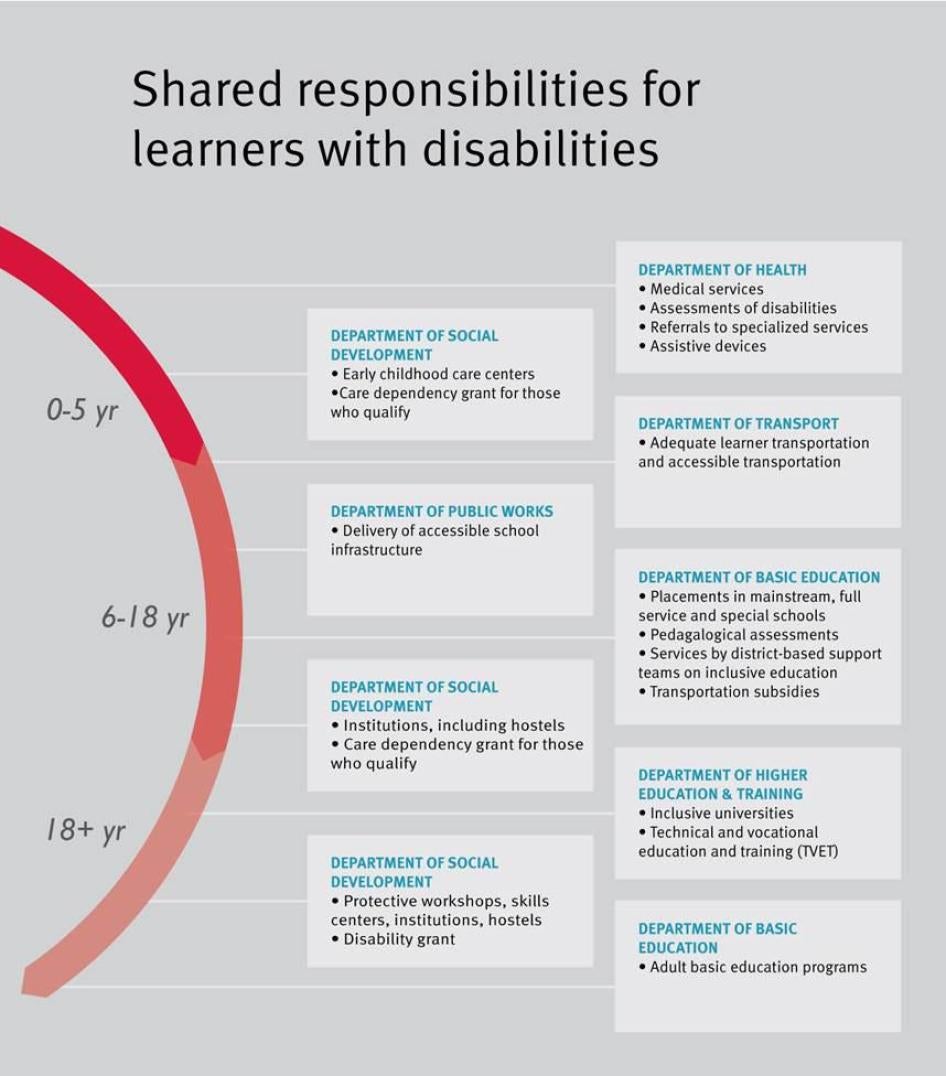

Inter-Departmental Obligations

While the Department of Basic Education is responsible for delivering inclusive education in schools, other departments play a key role in implementing this policy.

Western Cape Ruling, 2010

In 2011, disability associations representing children with severe and profound intellectual disabilities[31] in the Western Cape brought a case against the national and provincial Department of Basic Education for failing to accommodate these children in public schools. Members of the Western Cape Forum for Intellectual Disability had advocated for the right to education of over 1,000 children in their care for over 13 years, to no avail.[32]

The presiding judge of the High Court of the Western Cape, the superior judicial body in the province, concluded that the government was “infringing the rights of the affected children” by failing to provide them with a basic education and “by not admitting the children concerned to special or other schools.…”[33]

Moreover, the judge declared that the Western Cape’s Department of Basic Education had failed to “take reasonable measures to make provision for the educational needs of severely and profoundly intellectually disabled children in the Western Cape,” thus breaching their constitutional rights to a basic education, protection from neglect or degradation, equality, and human dignity.[34]

The court directed South Africa’s government to ensure that every child with severe or profound intellectual disabilities in Western Cape “has affordable access to a basic education of an adequate quality.”[35]

II. International Standards

a. Right to Free and Compulsory Primary Education

International human rights law makes clear that all children have a right to free, compulsory primary education, free from discrimination.[36]

South Africa has ratified six key human rights treaties applicable to children, education, and persons with disabilities.[37] The government has agreed to respect and fulfill international and regional obligations to provide free, compulsory primary education available to all children,[38] ensure different forms of secondary education are available and accessible to every child, and take appropriate measures, such as the progressive introduction of free education[39] and offering financial assistance in case of need.[40]

In January 2015, South Africa ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which came into effect in April 2015. Upon ratification, South Africa included a declaration that the government “will give progressive effect to the right to education … within the framework of its National Education Policy and available resources.”[41]

According to leading South African human rights organizations, such a declaration represents a “worrying discrepancy,” particularly as it contradicts current practice and national interpretation and jurisprudence of key international obligations on the right to education; notably the obligation to guarantee the right to free and compulsory primary education to all children. [42]

In particular, the government’s declaration is incompatible with binding decisions by South Africa’s Constitutional Court, which has previously ruled that there is an immediate obligation to fulfill this right, and that education is not subject to the progressive realization provisions associated with some other economic and social rights protected under the Constitution.[43]

As a party to the ICESCR, South Africa must submit an action plan on how it will guarantee free and compulsory primary education to all children.[44]

b. Right to Access Inclusive, Quality Education

Inclusive education is an evolving educational approach, widely interpreted across countries.[45] The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines inclusive education as:

A process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all learners through inclusive practices in learning, cultures and communities and reducing exclusion within and from education. It involves changes and modifications in content approaches structures and strategies, with a common vision which covers all children of the appropriate age range and a conviction that it is the responsibility of the regular system to educate all children.[46]

At root, inclusive education focuses on the importance of ensuring that “the whole environment … [is] designed in a way that fosters inclusion and guarantees their [children with disabilities] equality in the entire process of their education.”[47] This includes the right to access quality learning, which focuses and builds children’s abilities, and for children to be provided with the level of support and effective individualized measures required to “facilitate their effective education.”[48]

Moreover, inclusive education takes into account the mutual benefits of bringing together all children. “The most powerful experience is that peers become disability advocates,” Edward Ndopu, an activist, told Human Rights Watch, “They become champions of accessibility and inclusion in the classroom.”[49]

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) promotes “the goal of full inclusion”[50] while at the same time considering “the best interests of the child.”[51] The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the United Nations human rights agency, states that:

The right of persons with disabilities to receive education in mainstream schools is included in article 24 (2) (a), which states that no student can be rejected from general education on the basis of disability. As an anti-discrimination measure, the “no-rejection clause” has immediate effect and is reinforced by reasonable accommodation[52] … forbidding the denial of admission into mainstream schools and guaranteeing continuity in education. Impairment based assessment to assign schools should be discontinued and support needs for effective participation in mainstream schools assessed…. The legal framework for education should require every measure possible to avoid exclusion.[53]

c. Right to Education on an Equal Basis

International law provides that persons with disabilities should access inclusive education on “an equal basis with others in the communities where they live,” and governments must provide reasonable accommodation of the individual’s requirements, as well as “effective individualized support measures in environments that maximize academic and social development.”[54] The government must ensure that children are not excluded from the education system on the basis of their disability.[55]

The Convention against Discrimination in Education, to which the government is bound since 2000, provides strong obligations on the government to eliminate any form of discrimination, whether in law, policy or practice, which could affect the realization of the right to education.[56]

According to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, “Every child has the right to receive an education of good quality which in turn requires a focus on the quality of the learning environment, of teaching and learning processes and materials, and of learning outputs.”[57] Under the Convention Against Discrimination in Education, states must “ensure that the standards of education are equivalent in all public educational institutions of the same level, and that the conditions relating to the quality of the education provided are also equivalent.”[58]

Moreover, the CRPD specifies that persons with disabilities have the right to access education “on an equal basis with others in the communities in which they live.”[59] Children should also enjoy “active participation in the community,” according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).[60]

While the Schools Act guarantees the right of children to access schools within their province,[61] the government’s inclusive education strategy set out to “expand provision and access to disabled learners within neighborhood schools alongside their non-disabled peers.”[62]

To ensure governments understand the difference between meaningful ‘inclusion’ over simply ‘integrating’ children with disabilities in an education system,[63] the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recommends that “the entire process of inclusive education” is accessible, including buildings, information and communication; “the whole environment of students with disabilities must be designed in a way that fosters inclusion and guarantees their equality in the entire process of their education.”[64]

d. Duty to Ensure Reasonable Accommodation

The CRPD places an onus on governments to ensure that “reasonable accommodation of the individual’s requirements is provided” and that “persons with disabilities receive the support required, within the general education system, to facilitate their effective education.”[65]

The CRPD defines “reasonable accommodation” as any “means necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with other of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[66]

According to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a government’s duty to provide reasonable accommodation is “enforceable from the moment an individual with an impairment needs it in a given situation … in order to enjoy her or his rights on an equal basis in a particular context.”[67]

In assessing “available resources” to guarantee “reasonable accommodation,” governments should recognize that inclusive education is a necessary investment in education systems and does not have to be costly or involve extensive changes to infrastructure.[68]

“Education White Paper 6” refers to broad approaches to accommodate learners’ needs and sets out ways the government should accommodate children and young people with disabilities. Schools “are encouraged to make the necessary arrangements, as far as practically possible, to make their facilities accessible to such learners [with special education needs].”[69]

In 2014, the government finalized the “National Uniform Minimum Norms and Standards for Public School Infrastructure,” applicable to all mainstream schools.[70] These outline the requirements for schools to function properly and to progressively provide high quality infrastructure. While some measures need to be put in place urgently, other crucial standards exclusively applicable to learners with disabilities are subject to a progressive approach. For example, while the government outlined the need to comply with “universal design measures” for schools catering to learners with disabilities, provisions must only be complied with by 2030.[71]

Since ratifying the CRPD in 2007, South Africa has not adopted a clear, binding definition of “reasonable accommodation” in its education guidelines.[72] Embedding this key principle in South African law and policy would assist in increasing the understanding by education officials at national, provincial and district level of their obligation to accommodate the needs and requirements of children with disabilities within the education system, and would create legally binding measures to ensure compliance at the school level.

III. Discriminatory Fees and Expenses

When my daughter turned six, I cried for her. Puseletso is the only child who hasn’t been to school…. Her brothers go to school nearby. But most schools for my daughter are very far. I don’t want my child to go to a school far from me.

—Dimakatso, mother of an 8-year-old girl with an intellectual disability, Johannesburg, October 2014

Among the factors that impede the ability of children with disabilities to access education are prohibitive costs associated, in particular, with school fees, transport, and special assistants.

Fees

The only one school that can offer a placement [for my son] is the one I can’t pay for.

—Reneilwe, mother of a 10-year-old boy with autism, Limpopo, October 2014

Primary education is not automatically free in South Africa.

In 2000, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which oversees the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child to which South Africa acceded in 1995, expressed concern that South Africa did not guarantee free primary education, and recommended that the government “take effective measures to ensure that primary education is available free to all.”[73]

In addition to breaching the government’s international obligation to guarantee primary education free of charge for all children, the current fee-based system particularly discriminates against children with disabilities who attend public special schools. This results in many children with disabilities paying school fees[74] that many children without disabilities do not, in addition to additional costs, such as uniforms, food, and transport.[75]

The Schools Act mandates that the state fund public schools on an equitable basis.[76] The government in turn requires that the governing bodies of public schools, made up of teachers, parents, and other community representatives, adopt a resolution for a school to charge fees, and supplement a school’s funding “by charging school fees and doing other reasonable forms of fund-raising.”[77]

Public schools may be classified as “no-fee” schools, a status granted to public schools by provincial governments, which means that those schools should not charge fees. Today, around 80 percent of schools benefit from a “no-fee” policy across the country,[78] and approximately 60 percent of the current school population accesses “no-fee” schools.[79]

Human Rights Watch found that no special schools are currently listed in any “no-fee” schools list produced by the government.[80]

The “no-fee” designation is based on the “economic level of the community around the school,” and on a quintile system from poorest to richest, whereby the lowest three quintiles do not pay fees in designated public schools.[81]

Although a significantly high number of students in special schools come from townships and predominantly poor areas of towns,[82] many public special schools in urban areas are located in wealthier suburbs previously inaccessible to the majority of children under apartheid.[83] The income level of surrounding communities and locations means many special schools fail the “needs” or “poverty” test used to assess a school’s access to recurrent public funding or to qualify as a “no-fee” school.[84]

School fees in special schools visited by Human Rights Watch ranged from R350-R750 (US$32-$68) per each of the year’s four terms. Some parents calculated paying as much as R5,000 ($454) per year in school fees alone. One parent in Cape Town described fees of R380 ($35) per month as “expensive,” while another in Zwelethemba township, Worcester, said fees of R200 ($18) per month were “difficult to pay.”[85] Parents with children who are referred to special schools which are far away from their families also pay for boarding or housing fees and transport for their children to travel long distances to school.[86]

The father of an 8-year-old boy with autism in Johannesburg struggles to pay the fees at his son’s special school in Johannesburg:

Most [students at] mainstream schools don’t have to pay. But for us, we have to pay school fees. Lots of parents who have children with disabilities can’t work—we have to take care of them 24 hours. Schools write to ask why we haven’t paid but they don’t understand our situation. The schools are away from our locations. All the [care dependency] grant is going towards the fees, so there’s no money for transport… and our children have equal rights?[87]

Albertina Sisulu Resource Centre, a public special school in Soweto, charges R300 ($27) per year for fees, according to the school’s principal. However, out of 250 students, only 75 can afford to pay the fees.[88] The principal said the money supplements funding from the government’s National School Nutrition Programme[89] and is used to buy groceries so that all students can eat the same food.[90]

Human Rights Watch also visited informal centers set up by parents from the most socially disadvantaged backgrounds to respond to the education needs of children not accommodated in formal care centers or special schools. Centers in Cape Town and Kimberley charged R250 ($23),[91] and R150 ($14)[92] per month respectively—an economically significant fee for single-parent households, as well as for parents who are unemployed or earn very low wages, whose living is often dependent on their child’s care dependency grant.

The “National Norms and Standards for School Funding,” the government’s guiding policy on school fees, and accompanying regulations, includes fee exemptions for families that cannot afford education.[93] However, some parents were unaware of such exemptions, had only partial information about them, or said they were not always easy to obtain because schools often required documents, such as affidavits from a police station, that were difficult for foreign national parents to obtain.[94] In some cases, schools waived fees based on parents’ individual circumstances.[95]

Despite having a fee waiver, Maria Mashimbaye, whose 11-year-old son attends a special school, struggles with additional costs:

I was [paying] R400 ($43) per month [for nappies] plus R150 ($14) for school fees. The school had a lot of food he was allergic to so they also asked me to prepare his food. I spoke to the school and said, ‘The grant doesn’t cover all this. My husband doesn’t support me.’ So they waived the fees. Still, now I pay R400 for transport plus R400 for nappies. But he is outgrowing kid nappies and adult nappies are even more expensive.[96]

Although government policy on school fee exemptions states that children who are beneficiaries of a child dependency grant, a social development grant given to families with children with severe disabilities who are in need of full-time support and special care, are automatically exempt from paying fees,[97] six parents reported paying for school fees and additional expenses with their grant.[98] One of them was the mother of Akani, a 9-year-old boy with Down Syndrome, who now attends a special school with boarding facilities 100 kilometers from his home, who was not offered a fee waiver: “The [care dependency] grant is R1350 ($145) per month – when I checked, money [from the grant] will be able to maintain his school fees. He needs to pay R750 ($68) per term.”[99]

Transport

Adequate transportation is crucial in enabling children with disabilities to go to school.[100]

Human Rights Watch met children who had to travel 30 to 100 kilometers to access the nearest school that would accommodate them.[101] The lack of inclusion or discrimination in nearby mainstream schools means some children with disabilities have no choice but to move to neighboring provinces and travel to bigger cities if they have been referred to special schools.[102]

Human Rights Watch found that transport fees represented an additional barrier for children with disabilities across the country and none of the students interviewed received government support or financial subsidies to get to schools.

Transport fees ranged from R150 ($14) to R580 ($53) per month in urban areas. However, in the remote and rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo provinces, there was no transport for schools that were up to 100 kilometers away. Parents in this position had to pay for one-way trips that cost around R150 ($14) to R300 ($27).

The CRPD protects the right to personal mobility of persons with disabilities, including their access to school.[103] The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has urged states to:

Set out appropriate policies and procedures to make public transportation safe [and] easily accessible to children with disabilities, and free of charge, whenever possible, taking into account the financial resources of the parents or others caring for the child.[104]

The Department of Basic Education and Department of Transport have not yet adopted a national learner transport policy, which has been in draft form or under discussion since 2009.[105] The absence of such a policy has left many gaps in the provision of adequate transportation for children with disabilities at the provincial level, where there is limited accommodation of students with disabilities in provincial policy and practice.[106] This results in unequal access to transportation or transport subsidies.[107]

While some special schools that Human Rights Watch visited organize transport for students,[108] parents have to pay a monthly fee for transport. Albertina Sisulu Resource Centre, for example, charges R300 ($27) per month. Bernard Lushozi, the school principal, said that if a parent had a child who was qualified to use the bus but could not afford to pay for it, they could “come twice a week to clean or supervise sports and help in the school.”[109]

Where schools have insufficient transportation or only cover a certain distance from the school, parents pay private drivers to take their children to school. In several cases, parents said it was difficult to cover such costs. For example, Mpotse Mofokeng said she could not afford to pay to send Katlego, her 7-year-old son, to a special school in Johannesburg approximately 30 kilometers from their township:

One boarding school said they could take him, but not to board. They could only board children with physical disabilities. So, he didn’t go… I could not afford transport. There was no direct transport and it was at least one hour’s trip, one way.[110]

Ten parents said they could not pay private drivers. A father told Human Rights Watch that “the school can understand [when you don’t pay] but if you don’t pay for [private] transport, then they’re not going to take your child. Schools should provide transport.”[111]

Moreover, private drivers often charged children with disabilities and parents an extra or double fee, particularly for transporting assistive devices such as wheelchairs or strollers.[112] Human Rights Watch also heard experiences of private taxi or “cabbie” drivers refusing to stop whenever they saw a child or a person in a wheelchair.[113] “Some drivers don’t want to stop to put a wheelchair in the back so children don’t even have access to transport,” Brian Tigere, a social worker in Polokwane, said.[114]

|

Bongiwe, a 17-year-old girl with severe physical disabilities in Kwa-Ngwanase (Manguzi), uses a wheelchair. A private driver charged her R260 ($24) per month—an amount he doubled to pick her up by her doorstep rather than by the nearby tarmac road that she could only get to if her mother carried her.[115] Bongiwe’s mother hired several drivers throughout the school year; none fulfilled their jobs consistently. One driver was consistently late and often dropped Bongiwe last, after assembly time. Bongiwe’s mom complained numerous times, because “when she’s late the children are in the assembly. No one can help her into the school. There are no ramps in the school so she can’t get in.” Bongiwe’s last driver stopped picking her up altogether, causing her to drop out of school in the middle of the 2014-2015 academic year. Although her principal was told about the situation, the school took no further action to support Bongiwe: “I feel pain because I can’t take my exams like everyone else … I have lost a year.”[116] |

Special Assistants

A number of NGOs and experts told Human Rights Watch that, throughout the country, parents of children with disabilities are asked to hire and pay for private special care assistants as a pre-condition to enroll in a mainstream classroom.[117] Three children with physical disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch who attended mainstream and full-service schools also said they were asked to hire and pay for private special or class assistants as a pre-condition to enroll in their schools.[118] In one case, the mother of a 10-year-old boy with cerebral palsy was told she would have to move to the special school 100 kilometers away from their village to help her son eat and move around school.[119]

Privately hired class assistants often help children move around schools. They may carry children around because schools have inadequate access for wheelchairs or lack ramps, help them to use textbooks or materials in class, feed them, or take them to the toilet.[120]

Such conditions in schools discriminate against children with disabilities, who would otherwise not be able to participate and learn on an equal basis with all children in mainstream environments. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommends that governments provide personal assistance, among other necessary tools, so that children can fully exercise their right to education.[121] Currently, the Department of Basic Education or school-governing bodies are not required to pay for private facilitators or class assistants.[122]

IV. Discrimination in Access to Education

We don’t mainstream, we are dumping [children].

—Basie Jahnig, principal, Boitumelo Special School, Kimberley, November 2014[123]

If the children are old and out of school, it’s not their fault, it’s the government’s fault.

—Kululiwe, member of Siphilisa Isizwe disability organization, Kwa-Ngwanase, November 2014[124]

Several factors impede the ability of children with disabilities to access education at an appropriate age, including problematic referrals and too-long waiting lists.

Basic education is compulsory in South Africa: all children should be in school by the age of compulsory education, mandated as 5 to 6 years for grade R or pre-school, and 7 to 15 years for basic education.[125] In 1996, the Schools Act directed the minister of Basic Education to publish a government gazette with the compulsory age requirements for “learners with special education needs.”[126] As of May 2015, this document had not been published.[127]

Human Rights Watch found that many children with disabilities are denied an education because of their disability, or the needs and support they may need to learn on an equal basis in schools.

Sandile, a 10-year-old boy who is deaf and has partial sight, has never been to school. His mother, Nomsa, said she had never tried to register him in the mainstream school nearby, where his twin sister is enrolled. “I wish it could be like that but because he’s blind he can’t go to that school,” she said. Instead, doctors first referred him to a special school in Durban but told them to wait. Sandile was later placed on a waiting list for a special school for children with intellectual and physical disabilities that many children in Kwa-Ngwanase are referred to, but “they don’t accept the blind kids,” said Nomsa.[128]

Many children with disabilities who do access the education system do so when they are much older than students without disabilities. Thirteen children, ranging from 8 to 16 years old, and four young adults with disabilities interviewed by Human Rights Watch had not entered school at the age stipulated in South African law, as a result of long waiting lists and referrals to different special schools. Eight children with disabilities, ranging from 7 years to 15 years old, were registered in day care centers or crèches, waiting for school placements.

Problematic Referrals

The way that school officials make referrals and decisions about enrollment—specifically, failing to include children with disabilities in mainstream settings in the early years of education, and referring those who are already in mainstream schools to special schools—often compromises the experiences of children and young adults with disabilities, and their lifelong education opportunities.

Academic research and reports by national NGOs have confirmed the widespread practice of placing children with disabilities in special schools, based on an assessment of their disability rather than on their abilities and the level of need and support needed to ensure they can learn in a local mainstream school.[129]

Human Rights Watch found that 10 of the 70 children interviewed who attended mainstream or full-service schools, were waiting for a referral to a special school because their current schools could or would no longer accommodate them.

Such practices contradict the government’s broader aim of achieving inclusive education by ensuring children with disabilities can attend nearby mainstream schools, while being guaranteed adequate support through reasonable accommodations.[130]

The UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has repeatedly called on states party to the CRPD to end the segregation of children with disabilities, and to “take necessary steps to ensure that pupils who attend special schools are enrolled in inclusive schools,”[131] “establish and define goals and timeframes to ensure students with disabilities transition from special needs education to inclusive schools,”[132] and “reallocate resources from the special education system to promote inclusive education in mainstream schools.”[133]

Historically, children with intellectual or multiple disabilities, and children with autism spectrum disorder, have not been able to access public schools of any type, because of the limited availability of schools tailored to their needs, as well as discriminatory attitudes about the value of education for children with their needs.[134]

Members of the Campaign to Promote the Right to Education for Children with Disabilities, as well as service providers and experts across the country, told Human Rights Watch that, while some progress has been made at a provincial level to address the issue,[135] children with “severe and profound” disabilities across the country are still affected in their access to any public school.[136]

Arbitrary and Unchecked School Decision-Making

There is a problem with gate-keeping in schools. Schools are not admitting children in the first place to avoid predictable drop-outs.

—Henry Hendricks, general secretary, NAPTOSA, January 2015[137]

Robyn Beere, director of Inclusive Education South Africa, an organization that provides support and advice on inclusive education to parents of children with disabilities, warned that the government needs to think carefully about what type of school children with disabilities are placed in, particularly closely examining and vetting referrals to special schools, for “[they] are fundamentally changing a child’s life and placing limitations on the child.”[138]

Mainstream Schools

At a special needs day care center in Zwelethemba, near Worcester, only two out of nineteen children proceeded on to a mainstream school in 2013, according to the center’s director.[139] One was a girl with Down Syndrome. The center’s director, told Human Rights Watch:

We noticed she was very bright. The educational psychologist said she should be at the mainstream school. She went there [from the early childhood center], but she would often leave the classroom and wander around the class. She was then sent [by the mainstream school] to a special school.[140]

Inclusive education experts strongly believe that children with Down Syndrome, as many other children with disabilities, thrive and benefit the most when they learn in mainstream environments and should be accommodated in mainstream schools with the right level of support.[141] Various practitioners pointed out many cases where schools have done this successfully.[142]

Yet, inclusive education organizations following and monitoring individual children’s cases told Human Rights Watch that a large number of children with Down Syndrome continue to be referred to special schools, especially in rural areas.[143]

In Kwa-Ngwanase, Thandi told Human Rights Watch that Qinisela, her 8-year-old son with Down Syndrome, has never been in school. She said:

We tried to put him in a [mainstream] school but they said they couldn’t put him in that school because he has disabilities. The school said that he was naughty. Because of Down Syndrome he isn’t like other children so they [said they] can’t teach him. At the therapy they promised to phone if there’s a space in a special school. I’ve been waiting since last year.[144]

Similarly, the mother of Akani, a 9-year-old boy with Down Syndrome, who now attends a boarding special school, said:

He was in that [mainstream] primary school for three months. After they explained my child wasn’t coping, he stayed with me at home. I registered him in a special school. There was no other school where he would be admitted. I phoned the school and asked if they could make arrangements and was told that I would have to wait until next year. I went to other schools. In another primary school, they said they couldn’t accommodate him. They never recommended another school, they first said ‘no.’[145]

As a consequence of exclusion, small nongovernmental schools are being established to enroll children with various types of disabilities who were often turned down in public schools.[146]

In the Western Cape alone, between 70 and 80 out of 1,000 babies are born with fetal alcohol syndrome.[147] Yet, according to practitioners, because fetal alcohol syndrome is not a visible disability and mainstream schools do not address the particular learning and behavioral challenges faced by many children with the syndrome, children drop out of mainstream schools or become absent for long periods.[148]

Human Rights Watch visited the Home of Hope school, outside Cape Town, which focused on children with fetal alcohol syndrome disorder living in foster care who had dropped out or been forced out of mainstream schools due to behavioral and learning issues.[149] Children with this syndrome often manifest deep behavioral issues.[150]

Aisling Foley, an education manager at Home of Hope, told Human Rights Watch that it is difficult to find adequate placements for children with this syndrome who have dropped out of school because they do not meet the necessary intelligence quotient (IQ) levels to enter special schools and are often not accepted in mainstream schools due to behavioral issues.[151]

Human Rights Watch met Anne-Marie, a 15-year-old girl with fetal alcohol syndrome disorder manifested in an intellectual disability. According to her teacher at Home of Hope, she was deemed uneducable in her previous mainstream school and dropped out. Through individualized learning geared at her level of need, teachers have been able to ensure she is able to reach a basic level of understanding and gain basic skills.[152]

But experts maintain that most mainstream schools will not give children with fetal alcohol syndrome the same level of dedicated attention and they will drop out as a result.[153]

Parents of children with autism and NGOs supporting their families told Human Rights Watch that there is not enough specialized attention in all types of public schools.[154]

Autism experts told Human Rights Watch that “highly functioning” children with autism, such as children with Asperger’s Syndrome, currently do not receive adequate support in mainstream schools but could be accommodated with the right level of support and dedicated attention to avoid them being left unaccompanied, which increases the risk of bullying and anxiety. [155]

Children with physical disabilities also face exclusion in mainstream schools.[156] Edward Ndopu, an activist with skeletal muscular atrophy, who studied in mainstream schools, told Human Rights Watch that “schools are complicit in [the] exclusion. There isn’t really a culture of accessibility institutionalized in the school because we have to make it work.” Being the only learner in a wheelchair requiring special assistance in a mainstream environment meant that he “was there but operating on someone else’s standards.”[157]

Special Schools

Although the Schools Act prohibits schools from using assessments to prevent a student enrolling,[158] Human Rights Watch was regularly told that some special schools carry out their own assessments prior to admitting children conditionally.[159]

Human Rights Watch read email exchanges between the father of a 10-year-old boy with autism and a special school and resource center that caters to children with intellectual disabilities. Only after considerable discussions with the Western Cape Department of Basic Education[160] did the school agree to assess the child, who had been on a waiting list for two years. School officials informed the father that his son could join the school for a six-month observation period, but did not guarantee him a full-time place in the school.[161]

Children with autism spectrum disorder are most often misplaced or excluded from schools due to misunderstanding regarding their needs and behaviors.[162] Despite rising numbers of children diagnosed with autism in South Africa every year,[163] the government reported in 2012 that only 2,753 such children were enrolled in special schools, and 1,209 enrolled in mainstream schools.[164]

Nerina Nel, from the Children’s DisABILITY Training Centre, a nongovernmental organization focused on building capacity of teachers working with children with autism spectrum disorder, told Human Rights Watch: “It is typical that special schools don’t take children with autism or they’re kicked out. A child gets a place, but a week later, parents are called back and asked to take the child back.”[165]

Lebohang, a 13-year-old boy with autism was given little choice but to leave his special school. His mother told Human Rights Watch:

The principal asked me to choose between leaving him in the [special] school and pay for whatever he had damaged at school or take him out. I don’t work so I can’t pay for things, so I took him out. In the school they didn’t know about autism. Now the school says they don’t want autistic children. They made an example out of him.[166]

Similarly, while the government has officially acknowledged the major challenges experienced by incontinent children when accessing education,[167] children who cannot use or access toilets independently, or those who use diapers, often face very significant, discriminatory, barriers when accessing special schools.[168]

One principal told Human Rights Watch that her special school cannot take students with toilet needs because they cannot provide teachers or assistants to handle them.[169] Such decisions and limitations at a school level left children like Lesley, a 10-year-old boy with spina bifida and whose legs are paralyzed, out of school for over three years. Lesley was turned down by four out of nine special schools because of his toilet requirements.[170]

Waiting Lists

The government’s admissions policy states that a referral of a learner with special needs “should be handled as a matter of urgency to facilitate the admission of a learner as soon as possible to ensure that the learner is not prejudiced in receiving appropriate education.”[171]

In 2015, the government estimated that 5,552 learners with disabilities were on waiting lists.[172]

Evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch suggests that a lack of governmental oversight of waiting lists and placements leaves schools with the last word on enrolling students, further delaying children’s entry into schools beyond the age of compulsory enrollment.

Human Rights Watch met 21 children of varying ages and disabilities who were not in school, but waiting for a placement in a special school. Long waiting lists mean that admission can be delayed year after year. “They showed me three [registration] books full of names and said there are really no chances; but they asked me to go back in January,” said Marrieta, the mother of Bulelani, a 7-year-old boy with speech and physical disabilities who was out of school at time of writing.[173]

Nonkululeko, mother of Nkosiyazi, a 12-year-old boy with cerebral palsy, who is waiting for a referral to a special school, said she had “given up” trying. “Therapists, doctors called the school,” she said. “They said he’s on a waiting list and when I go to ask [the school] they say it’s full. 2013, 2014. They [doctors] never talk about it anymore.” Her son has repeated Grade 3 three times at the district’s only full-service school.[174]

Government policy on admissions states that students can only be removed from an attendance list once a transfer to another school has come into effect.[175] Matilda described what happened after a special school told her it would accept her daughter, a 10-year-old with an intellectual disability and epilepsy, who has been out of school for over two years.

I had bought the school uniform and everything. Then they told me my daughter had to wait. When I went to re-register her in the full-service school she was in originally, they said that she was already registered in the special school and they couldn’t take her back.[176]

Nongovernmental representatives told Human Rights Watch that it is hard for NGOs to get up-to-date or transparent information from many special schools.[177] “Schools duck and dive when you ask them for the waiting list,” Mary Moeketsi, an autism expert, said. “Some don’t want to show it.”[178]

Jean Elphick, program manager at Afrika Tikkun, an NGO providing assistance and empowerment programs for mothers of children with disabilities, said that some waiting lists in special schools around Johannesburg are 200 to 400 students long.[179] Two special centers and special school managers or principals told Human Rights Watch they no longer tell parents there is a waiting list. If they have reached maximum intake capacity, they ensure parents turn to other centers to seek placements for their children.[180]

Marie Schoeman, chief education specialist at the government’s inclusive education unit, believes the new “Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support” policy, published in December 2014, would help to alleviate delays in placements and waiting lists by ensuring young children go through an adequate screening to assess the most adequate learning environment for them.[181]

V. Discrimination due to Lack of Reasonable Accommodation in School

It is about tackling the fundamental issues: not just things that need improvement. We come up with a complete lack of [basic] implementation.

—Commissioner Lindiwe Mokate, South African Human Rights Commission, February 2015

Children with disabilities also face discrimination due to a lack of support in their schools. This also includes a lack of appropriate learning materials and subjects.

Evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch and nongovernmental organizations working with children with disabilities, as well as investigations carried out by the South African Human Rights Commission, suggest the government has not provided sufficient reasonable accommodation—or support—to ensure children with disabilities can access education on an equal basis as other children.

Lack of reasonable accommodation impacts children with various types of disabilities attending all types of public schools.[182]Many of the physical and attitudinal barriers documented fail to respect accessibility requirements in the CRPD.[183]

These students confronted the challenges of having no ramps to access classrooms or toilets.[184] Makhosi, a 23-year-old woman with severe physical disabilities, said: “I still have the same problems with access and ramps. I need to be carried everywhere … there were no ramps to go to the toilet. I wasn’t happy at school and wanted to move.”[185]

The lack of reasonable accommodation also translated into children being treated differently when they needed extra time to reach their often inaccessible classrooms[186] or take exams.[187] Michaela wrote:

The stairs are always an issue. The boys who help me are fine. I don’t think they mind but there are others who run away when they see that I need help… I feel like I am a burden to the people who help me … The teachers, not mine, teachers who don’t know me, make me feel like I’m just taking up space in the passages and that I waste their time because sometimes I need people out of their class to help me open a door.[188]

Makhosi shared that her “first problem was when we were writing exams … I was not finishing the exam on time because I write slowly … the teachers don’t give me enough time, they aren’t patient with me. The school said I should write to Pretoria to ask for more time for my exams for the next academic year.”[189]

Lack of Appropriate Learning Material and Subjects

The CRPD states that people who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind, or have low vision have the right to access “the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual, and in environments which maximize academic and social development.”[190]

Advocate Bokankatla Joseph Malatji, disabilities commissioner at South Africa’s Human Rights Commission, told Human Rights Watch that children with sensory disabilities face exclusion across the education system due to the lack of materials in Braille and sign language in mainstream and special schools.[191]

Despite President Jakob Zuma’s official announcement that sign language would become an official language in South Africa’s schools,[192] children who are deaf or hard of hearing face barriers learning sign language, particularly given the limited availability of specialized centers that teach sign language,[193] and the lack of teachers who can teach sign language to an adequate standard.[194] Phelele, 9, from Manguzi, was only taught sign language by his speech therapist, outside school. His parents told Human Rights Watch that teachers were not trained to sign in his mainstream school.[195]

In addition, serious systemic and administrative failures continue to mean there is a lack of appropriate textbooks for children who are blind or have low vision.[196] Cathy Donaldson, president of Blind SA, told Human Rights Watch that many children have been waiting for textbooks for the last three academic years due to delays in printing.[197] The government reported in 2015 that it has slowly increased the provision of Braille textbooks and sign language in schools.[198]

To cover this gap, teachers at Prinshof School for the Blind and Visually Impaired translate textbooks and classroom materials into Braille every evening of term. Yet, according to the school, Prinshof has the resources and staff to compensate for the lack of textbooks compared to other blind schools across the country.[199] Schools may incur enormous expense to buy their own materials.

Karin Swarz, Prinshof’s principal, told Human Rights Watch that the Braille master copy of one textbook is R24,000 ($2,170). According to the principal, the school bears the financial brunt of purchasing the original material, despite it being a clear obligation for the Department of Basic Education to ensure students who are blind have the necessary materials in order to learn the curriculum.[200]

Cathy Donaldson, the president of Blind SA, said other schools may not be able to cover the gap, resulting in students not using appropriate material[201] Moreover, translating textbooks takes time and resources—particularly where ordinary textbooks contain visuals that are hard to adapt for children with visual impairments.

Human Rights Watch was told that the government’s shift to a new “highly visual” curriculum in 2012, known as the “Curriculum Policy Assessment Statements,” made it more complex to ‘translate’ this into appropriate material for students who are blind or have low vision.[202]

Karin Swarz, for example, told Human Rights Watch that her school is one of the few special schools for children who are blind or have low vision which teaches mathematics, yet faces very significant challenges to do so.[203]

Tim Fish-Hodgson, a researcher at Section 27, a leading national litigation public interest law center, told Human Rights Watch that the lack of resources and appropriate material in many special schools have led them to phase out mathematics, literacy and application, for older students.[204] This may stop children who are blind or have low vision from studying mathematics, geography, sciences, business, economics or history.[205]