Summary

“The first time I went inside, I was 14 years old. I was scared. I kept thinking what would happen to me if something went wrong.”

—Jacob, 17, Malaya, Camarines Norte, June 2015

Thousands of children in the Philippines risk their lives every day mining gold. Children work in unstable 25-meter-deep pits that could collapse at any moment. They mine gold underwater, along the shore, or in rivers, with oxygen tubes in their mouths. They also process gold with mercury, a toxic metal, risking irreversible health damage from mercury poisoning.

The children described how they were terrified when climbing down shafts or diving into pits. They complained about the health effects of the work, such as back pain, skin infections, and muscle spasms consistent with symptoms of mercury poisoning. Human Rights Watch also interviewed witnesses to a fatal mining accident, in which a 17-year-old boy and his adult brother were asphyxiated in a deep pit mine in September 2014.

The government of the Philippines has not done nearly enough to protect children from the hazards of child labor in small-scale gold mining. Although the government has ratified treaties and enacted laws to combat the worst forms of child labor, it has largely failed to implement them: the government barely monitors child labor in mining and does not penalize employers or withdraw children from these dangerous work environments.

While the government has taken some important steps to ensure education for all, the number of out-of-school children working in gold mines remains a concern. Mining and environmental regulations for small-scale mines—including a March 2015 ban on mercury use and underwater mining—have gone unenforced, despite the government’s promise to reduce mercury and to make mining beneficial for the population.

Furthermore, while the Philippines has signed the 2013 Minamata Convention on Mercury, it has not yet ratified the treaty.

The government’s lack of concrete action reflects not only insufficient staff and technical capacity, but also a lack of political will by national and local officials to take measures that will not be well-received by the local population in impoverished areas, or by mine owners and traders that rely on child labor.

The government should improve child labor monitoring and child protection systems, and do more to reach those who have dropped out of school. It should ensure that its programs to address the ill-effects of poverty, such as free school meals and social support programs, are reaching families in mining areas, who frequently depend on the labor of children for survival.

With regard to mining, the government should support the creation of a legal, regulated, child-labor-free, small-scale gold mining sector that helps rural families thrive. It should also ratify and implement the Minamata Convention, notably by introducing mercury-free processing methods and taking special steps to protect children from mercury.

Others, too, should act to end child labor in this sector. The country’s central bank, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, buys gold from local traders and exports it, but has no process in place to check the conditions in which the gold has been mined. The central bank, as well as international gold trading and refining companies, should put in place robust safeguards to trace the gold back to the mines of origin, oblige their suppliers to source only child-labor-free gold, and monitor child labor.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted field research for this report in November 2014 and June 2015 in the provinces of Camarines Norte and Masbate in the Bicol region of the Philippines.

uman Rights Watch researchers interviewed 135 people, including 65 children working in artisanal and small-scale mining: 44 boys and 21 girls. In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed four young miners, aged 18 and 19, who had started working as children. Human Rights Watch also interviewed government officials, including barangay (village and district) officials and representatives of relevant ministries, traders, teachers, health workers, mining experts, and representatives of international agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

When possible, Human Rights Watch carried out interviews with children in a private setting, without others present. Because of the difficulty of maintaining privacy on mining sites, some interviews were conducted in the presence of other children or a few adults. Interviews were conducted in Tagalog, with the help of an interpreter where necessary. Interviewees were not compensated for speaking to us.

The names of all children have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their privacy.

I. Child Labor in Small-Scale Gold Mines

“Small-scale gold mining” is defined under Philippine law as mining with either no or simple machinery and a large workforce.[1] Such small mines are also called artisanal mines. This report uses the term “small-scale gold mining” to encompass artisanal and small-scale mining more broadly.

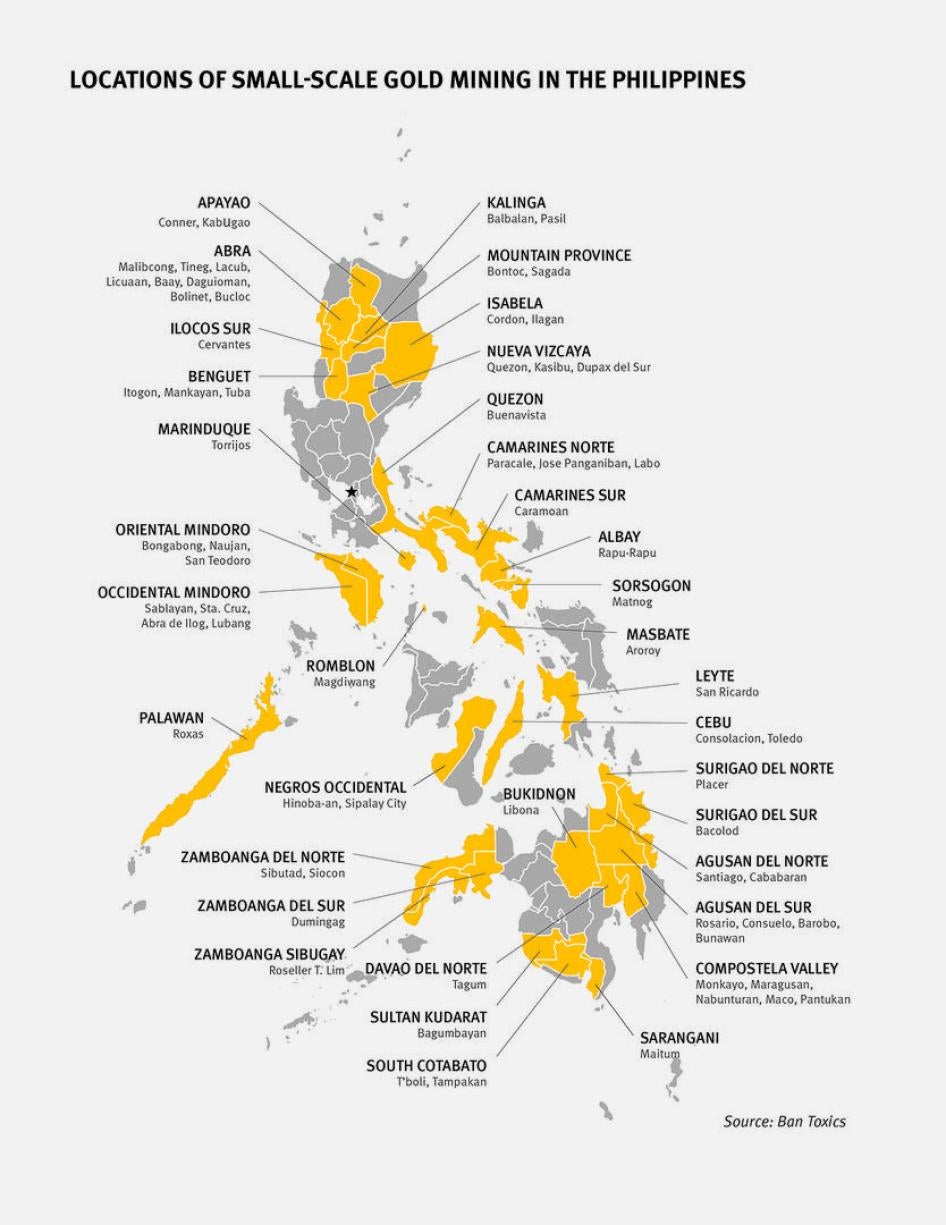

Small-scale gold mining occurs in more than 30 provinces of the Philippines, and is an important livelihood for many poor, rural communities.[2]Small-scale mines largely belong to the informal sector.

An estimated 200,000 to 300,000 people work in small-scale gold mining.[3]Large and small-scale mines produced about 18 tons of gold in 2014, at a market value of over US$700 million, according to official statistics.[4] There are no reliable figures on the production of gold from small-scale mining because an estimated 90 percent of the gold is smuggled out of the country and not traded at the government-controlled buying stations.[5] It has been estimated that 70 to 80 percent of gold in the Philippines originates from small-scale gold mining.[6]

Under Philippine law, the government can designate specific “people’s mining areas” (minahang bayan) where small-scale mining is permitted for miners holding a valid license.[7] In practice, there are only four such areas in the whole country, and almost all small-scale miners operate without a license outside such designated lands.[8]

Businessmen finance the mining operations and machines—such as air compressors, blowers, or ball mills to grind ore—and get a profit in return.[9]

In March 2015, the government revised the rules and regulations for small-scale mining. In order to increase the number of legal mining operations, the government simplified the process for obtaining licenses and declaring people’s mining areas.[10] The government also prohibited certain harmful mining practices, including the use of mercury and underwater (so-called compressor) mining.[11] However, it did not mention child labor or reiterate the prohibition on child labor.

Under Philippine law, the minimum age for work is 15, and hazardous work is prohibited for anyone under the age of 18.[12] The Philippines has ratified international laws on child labor, in particular the International Labour Organization (ILO) Minimum Age Convention and the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, which defines work underground, work underwater, and work with hazardous substances as hazardous and, therefore, among the worst forms of child labor.[13] In 2013, the Philippines also passed an Enhanced Basic Education Act, which mandates compulsory free education for all children in the Philippines until the age of 18.[14]

Despite this strong legal framework, child labor is common. According to a 2011 child labor survey, about 3 million children work in hazardous conditions in the Philippines.[15] The main underlying cause for this is family poverty. Many children who work do not attend school. An estimated 3.5 million children are out of school.[16]

A recent study by a Philippine nongovernmental organization (NGO) found that 14 percent of children who live in mining areas work in mining.[17] The majority of child laborers were between the ages of 11 and 17, but younger children were found to be working in mining too. According to a 2009 statement by the ILO, over 18,000 girls and boys work in mining in the Philippines.[18] Much of the children’s work in the Philippines mines is hazardous and falls under the worst forms of child labor.

Underwater Mining

In the Philippines, many of the gold deposits are beneath the water table. A unique practice, known as compressor mining, has developed in coastal areas along the shore, in rivers, and in swampy areas. Diving underwater for several hours in 10-meter-deep shafts, miners receive air from a tube attached to a diesel-run air compressor at the surface. This extremely dangerous work is mostly carried out by adult men, but sometimes also boys.

Human Rights Watch interviewed seven boys working in compressor mining and three young adults who started this work as children. They described their moments of fear when they dived for the first time. Dennis, 14, said: “I was 13 the first time [I dived]. I felt scared because it’s dark and deep, and it was my first time…. Now I’m used to it.”[19]

A boy who pulled sacks of ore up at a compressor mining site had, on the day he spoke with Human Rights Watch, made his first attempt to dive for gold: “I tried today to go inside but I could only last one minute. It was cold. It was very dark and when I came up I was really cold.”[20]

The divers usually enter a narrow wooden shaft (approximately 70 x 70 centimeters) that has been dug into the bottom of the ocean or river. Some stay for an hour, others remain three hours under water, sometimes longer. Several boys told Human Rights Watch how they got extremely cold because of the long time spent under water.

Seventeen-year-old Samuel said: “It is very cold inside and it’s so dark. The scary part is when you just start to build [dig a tunnel in the riverbed] and all of it is mud.”[21]

Those who dive for gold risk drowning from lack of oxygen or mudslides. In some cases, the compressor tubes providing divers with oxygen stopped working and forced them to come up for air quickly. One diver, Joseph, 16, said:

Sometimes you have to make it up fast, especially if you have no air in your hose if the machine stops working. It’s a normal thing. It’s happened to me.[22]

However, coming up fast from diving deep in the water is also dangerous. Small nitrogen bubbles can build in the person’s blood and cause “the bends,” or decompression sickness. This can result in pain in the joints, shortness of breath, brain disorders, or an embolism.[23]

Compressor mining also carries other health risks. Children working for extended periods in water often suffer itchy and infected skin, a condition locally called romborombo.[24] Such infections can be caused by bacteria in the water.[25] In addition, children are exposed to carbon monoxide from the diesel compressors, increasing the long-term risk of lung cancer.[26]

In March 2015, the government of the Philippines prohibited compressor mining.[27] Prior to that, some barangays had already passed ordinances banning the practice locally.[28] While compressor mining appears to have reduced in recent years, it remains an important livelihood in Camarines Norte and continues, despite the ban.

Mining in Underground Pits

Boys also work alongside adult miners in dry underground pits that are up to 25 meters deep. They are usually lowered into the pit on a rope and work there for several hours. If the pits are deep, oxygen is pumped in with a blower. If the pits are not so deep, miners work without a blower, but often find it difficult to breathe.

The risks of underground mining became apparent when two brothers—Nel Pernecita, 17, and Joven Pernecita, 31—died in a pit in Malaya, a mining village near Labo, Camarines Norte, in September 2014. Local officials and their relatives concluded that the boy and his older brother, who had come to rescue him, died of asphyxiation.[29] The brothers had entered the pit on their own initiative, after having done some other mining work. The owner of the mine was present and did not stop them, saying that he accepts children as workers because, “I don’t meddle in what they do.”[30] When a third brother entered the mine to check on the other two, he found them dead. The deaths deeply affected the community, yet boys and men continued to work underground.[31]

Human Rights Watch spoke to several boys working underground. Andres, 14, had worked underground, but, at the time of the interview, was doing other mining work. He worked 12 hours a day with one lunch break above ground around noon.[32] He said:

Sometimes I would accidentally drop the sack of ore on my toes. It’s 30 kilos…. It’s tough, carrying the ore and pulling it. It’s so heavy that when I take a rest, I feel weak…. I didn’t like being there. It’s tough being there. It’s frightening because it might collapse.[33]

Some boys even work 24-hour shifts: They enter the pit in the morning and work one full day and night, only exiting for short breaks to eat.[34]

Child laborers spoke of accidents they suffered in underground pits, caused by falling rocks or wooden beams, by falls, or from the tools they were using. Andrew, 14, who works near the large-scale Filminera mine in Masbate, explained:

I’ve been working in the mines a long time. I would go along with my father. He goes to the mountains and the tunnels. I go inside too. The tunnels are deep. My father and I would get ore and bring them to the surface. The ore is in sacks… Oftentimes we would spend the whole night in the mines and go home at 4 in the morning….

I fell down the tunnel in 2011 when I slipped and a wire injured my arm. This was operated on. I spent a day in the hospital….

I also saw an incident of bardown [mine collapse]. One of the panners was crushed to death, his eyes bulged out of their sockets. Bardowns are common in our area and it happens when there’s blasting by Filminera. It feels like an earthquake each time.[35]

Edwin, 17, told Human Rights Watch:

One time, when we were down in the pit, my companions were bringing down lumber. The rope around the wood loosened and the lumber fell down on us. Fortunately, we managed to evade it. If not, we would have died there.[36]

Carrying Heavy Loads

Child laborers—even very young children—often carry heavy loads, both when working undergroundand above ground. Several children interviewed complained about pain in their back, shoulders, sides, or hands, from lifting and carrying heavy sacks of ore.

One of them was 9-year-old David, who carries rocks at the Boston mine in barangay Capsay, Masbate province, along with many other small children.[37] He told Human Rights Watch that his back and feet hurt from carrying the heavy ore from the tunnel to the ball mill.[38]Girls also described pain from carrying heavy loads.[39]

Richard, who is about 10, described his work:

I get the stones and crush them with a hammer. I do this every day. I also put the stones into the ball mill and later pan them…. When I carry the sacks of ore, my sides hurt….[Two days ago], when I carried the rocks, one rock fell down and hurt my leg. It was bleeding. I put [a healing grass]. I continued working.[40]

In the long term, carrying heavy loads is harmful for children because it can cause spinal damage.[41]

Processing Gold with Mercury

Many miners who work in artisanal and small-scale gold mining pan for gold and process it with mercury—a liquid, toxic metal that attracts the gold particles and forms an amalgam with the gold. It is affordable and easy to use. Processing with mercury is often done by children, including many girls.

Due to the common use of mercury in artisanal and small-scale gold mining, the Philippines discharges about 70 tons of mercury into the environment each year.[42] Only in the northern province of Benguet do miners process gold without mercury, by concentrating the ore first and then smelting it (also called the “direct smelting” or “borax method”).[43]

Mercury attacks the central nervous system and can cause lifelong disability, including brain damage, and even death. Mercury is particularly harmful to children, as their systems are still developing; the younger the child, the more serious the risk.[44] It is a threat to all who are exposed to it, not only those working with it. Numerous studies indicate that artisanal and small-scale gold miners in the Philippines have a significantly higher mercury burden than residents who do not live or work in mining areas.[45]

Because mercury accumulates in fish, fish near mining areas—such as, for example, in Mt. Dilwalwal in Mindanao—is heavily contaminated with mercury. This poses health risks for local communities that eat fish.[46] One study also found elevated mercury levels among schoolchildren located near a small-scale mining area.[47]According to the Department of Health, 10 adults and 2 children were diagnosed with mercury poisoning from small-scale gold mining in Romblon in 2012 alone.[48]

Miners use two methods of gold processing. In one method, the gold is concentrated by swirling the mixture in a round pan, a process called panning. Afterwards, mercury is added to attract the gold particles. The amalgam is separated from other soil and burned with a blowtorch, causing the mercury to evaporate as poisonous gas, and leaving behind raw gold.

A second method of mercury use is called “whole ore amalgamation” and is particularly harmful: large amounts of mercury are dumped directly into ball mills filled with the whole (unconcentrated) ore, and mixed in the running ball mill for a period of time, for example, 20 minutes. After this, the mercury-gold amalgam is retrieved and burned over a fire to obtain the gold. Tailings are washed away.[49] Human Rights Watch researchers observed the unrestricted flow of such light-grey, mercury-contaminated tailings in several mining areas. In Malaya, the mercury-contaminated tailings flowed straight into the Bosigon River, where children play, swim, and pan for gold.

Most of the child laborers interviewed by Human Rights Watch were working with mercury. The youngest child interviewed who burned the mercury-gold amalgam was 9 years old.[50]The children usually obtained the mercury from local traders. They mixed it into the ore with their bare hands and often also burned the amalgam, with nothing to protect them from the toxic fumes. Human Rights Watch observed children burning the amalgam in various settings, including indoors and inside homes, where young children and pregnant women were being exposed to the fumes.

One of the children working with mercury was 13-year-old Ruth. She told Human Rights Watch that she processes gold to ensure her family can buy food. She started working at the age of 9 and also dropped out of school at that age. She told Human Rights Watch researchers:

[When you arrived] I was panning the ore. I put mercury [in] and get gold from it… I also amalgamate and burn. I do that at the torch at the plant…. I give what I earn to my mother, who pays the owner of the ball mill 100 pesos (US$2.23) per cycle of processing…. [But] there are times when we got nothing for the bag.[51]

Ruth had not heard about the harmful effects of mercury. Most child laborers have limited, and sometimes false, information about mercury, and usually do not know its risks or how to protect themselves properly from this toxic metal. Some cover their mouths with their shirts when burning the amalgam—a measure that does not reduce the risk.

Human Rights Watch interviewed several adult and child miners who were suffering from tremors and spasms—symptoms that are consistent with mercury poisoning.[52]One of them was Aileen, who had started working in mining at the age of 8 and has been handling mercury since that age. She is now 15 and told Human Rights Watch about her work in a group of child miners:

I get the pan and the shovel and go to the creek, and I use the pan there. I scoop the rocks and sand from the water in the pan. We shake the pan for two minutes, and you get the fine sand…. Some would put the mercury in the pan in the river and others do it at the store, like me. We put the refined sand in the pot, then we add the mercury. We burn it off using the torch. We burn the amalgam in a clay pot…. I mix the mercury with my bare hands. It is fine sand and we mix with our hands until it's a paste-like consistency….

Nobody has ever told us how to handle mercury. Everything we do now we just copy from those who did it before…. I live with my parents. I have siblings. There are 12 of us. Four of us work in the creek. They are 11, 12, 14, and then I'm 15. I have an 18-year-old brother who goes to the pits and in the tunnels….

I just recovered from a fever because we still work, even in the rain. Panning is really hard because my body aches and my hands get blisters. I get spasms in my hands and my legs. Sometimes my hands feel like they are swollen…. There were times I would think about slashing my wrists because I couldn't take the hardship.[53]

Spasms, tremors, and skin conditions can be symptoms of mercury poisoning—but those interviewed had not been tested for mercury exposure, and Human Rights Watch could not determine the cause of the symptoms children reported. Local health centers cannot test for mercury poisoning, and often lack training on the effects of mercury poisoning.[54]

Panning in Water

Many children who pan for gold stand in water or are in contact with mud or water continuously, and sometimes suffer from skin conditions as a result.[55]Roy, 14, who pans for gold at a compressor mining site in Paracale, said he had romborombo: “It’s itchy and it burns, especially when it gets wet. I put ointment on it. I haven’t seen a doctor. It lasts four to five days.”[56]

Edgardo, 15, pans gold at a compressor mining site. He started working in small-scale mining when he was 10. He described his skin condition: “I have scars on my legs from a rash. It’s from the water here. It swells first, like chicken pox, and when I scratch it, it gets infected. I’ve had it ever since I started working.”[57]

Impact on Schooling

Work in small-scale gold mining causes children to skip school and sometimes drop out altogether. Nearly a third of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not go to school at all. One of them, Richard, dropped out in second grade. He said:

I ended school in Grade 2. I started panning after I dropped out, around the age of 8…. I dropped out of school because my father died. We are three siblings working here… The school did not follow up when I left. [58]

Teachers in mining areas stated that child labor in mining causes children to drop out or attend school irregularly. The head teacher of the primary school in Panique, Masbate, said: “Child labor in mining is one of the causes for drop-outs here.”[59]

Some child laborers attend school, but skip classes on a regular basis to work at the mines. For example, 13-year-old Anna said that she always skips school on Tuesdays to work with her mother.[60]A teacher in Malaya said that, “In extreme cases, we only see them [children working in mining] during exams. They’re absent the rest of the year.”[61]

Because children lack time to rest and study, their performance in school may suffer when they start working in mining. Children themselves, as well as teachers, noted that they are tired, slow, and unfocused due to their work in the mines.[62]Andrew, 14, who works underground, explained: “In school, I was often tired so that I often doze off. My seatmates would wake me up.”[63]

The main reason put forward by the children as to why they dropped out of school or skipped days was to help out their parents financially. In addition, several children said they went to work at the mines to earn money for school supplies.[64]

II. Government Response

Despite a strong legal and policy framework, the government of the Philippines has not done nearly enough to protect children against the harmful impact of child labor in mining. The government has done virtually nothing to monitor child labor in mining or withdraw children from work in the mines. It has also largely failed to implement its laws and regulations on small-scale gold mining, tolerating the social and environmental damage it causes.

The Philippines is a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The covenant protects, among other things, the rights to safe and healthy working conditions, education, and the highest available standard of health.[65]A state has an obligation to take steps by itself and with international assistance and co-operation “to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights” in the covenant.[66] The Philippines has also ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which provides a range of protections for children.[67]

Child Labor and Education

The Philippines has an ambitious legal and policy framework to eliminate child labor, but enforcement remains weak due to a lack of staff and technical capacity, a lack of political will by elected barangay officials to take unpopular measures, and a disconnect between the capital and decentralized local authorities.

Under Philippines law, the minimum age for work is 15, and hazardous work—including mining underground and underwater—is prohibited for anyone under 18.[68]Under the Philippine Program Against Child Labor (2007-2015) and the Convergence Program Against Child Labor, the country has set the goal of reducing the worst forms of child labor by 75 percent by 2015.[69]

For example, the government’s conditional cash transfer program for impoverished families specifically targets households of child laborers, and is complemented by other livelihood assistance programs.[70]The Campaign for Child-Labor Free Barangays seeks to assist local governments in creating child-labor free communities.[71]Local authorities also sometimes pass ordinances prohibiting child labor to reinforce national law.[72]

Under the leadership of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), various government agencies—such as the Department for Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and the Department of Education—work on child labor issues, and coordinate in the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC).

International donors view the efforts of the Philippines mostly positively. For example, the United States Department of Labor considers that the country has made “a significant advancement” in addressing child labor—an assessment that may be overly positive.[73]

However, practical action on the ground falls short of the government’s ambitious goals. Inspections do not occur systematically and are rare in the mining sector. While the number of labor inspectors has been increased by over 300 in recent years,[74]inspections still function poorly. According to the DOLE, barangays have to do the monitoring themselves as the department is not present on the ground (but based in regional and provincial capitals).[75]

The child-labor free barangay program only reaches a fraction of all barangays, and even those involved in the program have not been declared child-labor free.[76] Child protection and police capacity is also limited at barangay level.[77]With regard to child labor in mines, officials in Camarines Norte and Masbate told Human Rights Watch that labor inspectors had done no inspections.[78] The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has been invited to join the NCLC, but has not done so.[79]

Even when child labor is identified by other actors, government authorities do not always act swiftly. When a local newspaper reported about child labor in Masbate, the DSWD acknowledged that “no one was sanctioned nor held accountable.”[80]It described its awareness-raising activities on child labor, but also minimized the problem, stating that the children were not employed by anyone, but “working on their own.”[81]

With regard to education, the government has made important gains. In the Enhanced Basic Education Act, compulsory free education has been extended up to age 18, and various measures have been taken to increase school enrollment and make education more adapted to children’s needs.[82]For example, under the Alternative Learning System, the government sends mobile teachers to bring schooling to far-flung areas.[83]But, while primary school net enrollment is now at 89 percent, enrollment rates are far lower in high school.[84]According to the undersecretary in the Department of Education: “Our problem now is [that] enrollment in high school has been going down…. Either they don’t enroll or they just drop out.”[85]

About one in ten children between the ages of 6 and 14 is not attending school—in absolute numbers, the figure is at about 3.5 million children.[86]When children in primary or high school start to attend classes irregularly or drop out altogether, the government does not have a clear protocol in place to ensure steps are taken to bring the child back to school.[87] The government also does not have programs targeting mining areas specifically.[88]

Mining and Mercury Exposure

The Philippine government has largely failed to enforce its laws, regulations, and policies on small-scale mining and mercury. The main causes for this appear to be a lack of capacity, a disconnect between the central, regional, and local levels, and a lack of political will by local officials—some of whom have themselves invested in small-scale mining.

Almost all small-scale gold mining in the Philippines takes place outside the government-assigned minahang bayan areas and is de facto illegal. Mining inspectors, who are based in regional capitals, rarely inspect small-scale gold mines and have failed to enforce mining and environmental laws and regulations. But even when officials attempt to enforce the rules, they encounter problems. Officials of the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), which is part of the DENR, told Human Rights Watch that “our problem is that… the PNP [the Philippine National Police] should be the one to enforce it.”[89]

Government officials have commented that politicians and local authorities themselves are often involved in mining operations.[90]As a result, they have little interest in regulation.

For example, in September 2014, the Mines and Geosciences Bureau issued an order for small-scale gold mining operations in Malaya, Camarines Norte, to stop. The main reasons cited were environmental and work hazards.[91]But local authorities and the police took no steps to enforce the ban.[92]

The government’s actions on mercury have also been insufficient, despite its commitment to protect people and the environment from this toxic substance. The Philippines strongly supported the development of a new United Nations treaty on mercury, and signed the Minamata Convention on Mercury upon its adoption in 2013.[93] It is currently undertaking an assessment of the legislative framework and mercury emission, funded by the United Nations Environment Programme, but has not yet ratified the convention.[94]

The government has developed a National Strategic Plan for the Phase-Out of Mercury in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining 2011-2021, whose goals largely coincide with those of the Minamata Convention.[95]The plan has set a target to reduce mercury emissions by 25 percent in 2014 and 45 percent in 2017, eliminate harmful practices such as whole ore amalgamation and burning of amalgam in residential areas, and introduce mercury-free alternatives.[96] While the government has been involved in some implementation activities, a local nongovernmental group, Ban Toxics, has taken the lead, with the financial support of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO).[97] For example, Ban Toxics and the Department of Health have started to conduct health worker trainings on mercury.[98] However, four years after being launched, there is no clear mechanism to monitor implementation of the action plan. The government has also failed to assess whether the 2014 target, the reduction of mercury use by 25 percent, has been met.[99]

To gain more control over small-scale gold mining, the government has prohibited harmful mining practices and, simultaneously, sped up the process of formalization. In March 2015, the government adopted an administrative order that overhauls and clarifies the process for obtaining licenses and declaring people’s mining areas.[100]The administrative order also prohibits the use of mercury and compressor mining.[101] Before this order, mercury use had been allowed for mining, and compressor mining had only been banned through local ordinances.[102]

If these measures help increase government regulation and adherence to environmental and mining laws, they are a step in the right direction. However, by June 2015, three months after the adoption of the measure, illegal mining with mercury and underwater operations continued unabated.[103] Government officials in the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), part of the DENR, whom Human Rights Watch contacted about the administrative order, were unaware of its existence, and subsequently informed Human Rights Watch that the MGB is in charge of implementation.

Responsibilities of Gold Trading Companies

Under Philippine law, traders sell their gold to buying stations established by the Philippine central bank for that purpose.[104] Buying stations are located in the main mining areas of the country.[105] However, the bank has no safeguards in place to ensure that it does not benefit from child labor. An official of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas told Human Rights Watch:

We do not ask questions about how the gold is mined. No questions asked - it's part of our agreement. We do not have rules about child labor. It's up to the Department of Labor to address child labor.[106]

As set out in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, all companies have a responsibility to respect human rights. This means avoiding causing or contributing to human rights abuses through their own activities, and addressing abuses that occur. It also means preventing or mitigating adverse human rights abuses directly linked to their operations, even if they have not contributed to those abuses.[107]

For companies involved in gold mining in the Philippines, this responsibility means ensuring their operations do not contribute to child labor, including by allowing child labor to creep into their supply chains. Companies have a responsibility to put in place effective human rights due diligence mechanisms to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for companies’ negative impacts on human rights.[108]The Philippines’ central bank, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, as a government entity, has a particular responsibility not to contribute to human rights violations, and should be directed to undertake human rights due diligence, including specifically child rights due diligence.[109]

Recommendations

To the Government of the Philippines

- Develop a strategy to tackle child labor in mining and spell it out in the new child labor program, which will succeed the Philippines Program against Child Labor. As part of this strategy:

- Investigate and monitor child labor in small-scale gold mining, placing labor and mining inspectors closer to mining areas and providing them with the mandate and resources to conduct regular inspections;

- Improve the availability of social workers who are equipped to guide and support children’s transition out of child labor;

- Instruct the Department of Environment and Natural Resources to join the National Child Labor Committee and become directly involved in addressing child labor;

- Improve access to education for children working in small-scale mining, including by following up on students who are frequently absent from school or who drop out, offering bridging programs to get back into school, and using social protection measures to assist vulnerable children in mining areas;

- Offer appropriate part-time youth employment opportunities for adolescents between the ages of 15 and 17, that do not interfere with the compulsory schooling requirement for these children.

- Develop a comprehensive strategy for a responsible and safe small-scale mining sector. As part of this strategy:

- Enforce the March 2015 administrative order to ban mercury use and compressor mining;

- Implement the National Strategic Plan for the Phase-Out of Mercury in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining, including by introducing mercury-free gold processing methods and by ending the use of mercury by children;

- Ratify the Minamata Convention on Mercury and implement its provisions;

- Conduct biomonitoring in small-scale mining areas to assess levels of mercury exposure among local communities and provide treatment to those in need;

- Improve access to health care for children working in mines for mining-related health conditions, including mercury exposure.

- Direct the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, the Philippines’ central bank, to have thorough due diligence procedures in place to identify child labor and other human rights risks in the gold supply chain, including through a human rights policy, full chain-of-custody documentation, regular monitoring and inspections, contracts with suppliers prohibiting child labor, qualified third-party monitoring for child labor, and public reporting.

To Donors and UN Agencies

- Provide support to the government of the Philippines to implement the above recommendations, in particular in the areas of :

- child labor monitoring and support ton transition out of child labor;

- outreach to out-of-school children;

- appropriate youth employment;

- biomonitoring of children’s mercury levels in mining areas and;

- the introduction of mercury-free gold processing methods.

To International Gold Traders and Refiners

- Put in place thorough due diligence procedures to identify child labor and other human rights risks in gold supply chain, including through a human rights policy, full chain-of-custody documentation, regular monitoring and inspections, contracts with suppliers prohibiting child labor, qualified third-party monitoring for child labor, and public reporting.

Personal Stories

“Dennis,” age 14

I started [mining] when I was 12. I do the panning, but I also go underwater…. I was 13 the first time [I dove]. I felt scared because it’s dark and deep, and it was my first time. Now I’m used to it….

I go underwater using the compressor for air. You have to feel your surroundings to tell if the walls of your pit are going to collapse or not. Whenever I’m underwater, I am collecting a mixture of mud and stones that probably has gold in it. You cannot see anything underwater, so you have to use your sense of touch to recognize the stones you have to shovel. I wear a mask, and I put cotton into my ears. And I take a shovel down with me….

Sometimes, it feels like your eardrum is going to explode. I stay underwater for one to two hours. [Once] the man above me gave me the warning that something was wrong with the compressor, so I could immediately go up. Before it [the air] runs out, I have to go up….

Sometimes if the machine leaks, I smell the fumes. Sometimes I feel dizzy because it’s oil….

Sometimes I get romborombo [a skin condition]. It burns. Sometimes you can’t work. Sometimes you can’t walk. You can’t even sit. You get it on your butt. I treat it with ointments.

I’m in the first year of high school. Sometimes I have absences. Sometimes twice a week if I have no money for food for school. I live here with my family. I have a few siblings. We’re 11…. My mother and father are separated, so I need to work. My siblings do different work. … [In the future] I want to be a policeman so that I can help people.[110]

“Reynaldo,” age 15

I go inside the tunnel. I do the hammering of the gold. Sometimes I do errands like collecting firewood, water, etc. I also dig the muckup [soil] for a new tunnel. … We use tools, like hammer, chisel, shovels…

The pit is about 20 people deep. Sometimes I feel afraid because I may get hit by falling rocks…. Down there is a blower that provides air. I stay 12 hours down. I go down at 6 a.m. and stay till 12 noon. Then I go up for lunch, after lunch, I go down again until 6 in the evening. I do this three times a week, Monday to Wednesday. Thursday to Sunday I go to the Ecumenical Institute for Labor and Educational Research (EILER) school [an NGO-run bridging program].

Five months ago, there were two cases of air poisoning. Two brothers were killed. There was no air inside the tunnel. At the moment the two brothers entered the tunnel the blowers were not in operation. They did not know.… Now, my sister is worried that I might get trapped inside if the pit collapses. [111]

“Michelle,” age 15

I live in Malaya with my family. I live with my grandmother. My father is already dead. I have a brother in Manila. My mother works in a garment store in another city. She doesn't live here….

I go to the creek and pan for gold all day. In the creek, I take a shovel, get the dirt, and put it in the pan and I repeat the process.

EILER school [a bridging program for children who have dropped out of school] opens Thursday to Sunday. Monday to Wednesday, I go to the mine. I go at 7 or 8 a.m. to 4 in the afternoon. We don't usually take breaks because, if you don't work hard, you get nothing from this. But we do take a lunch break. I often work with my friends, sometimes with my grandmother. My friends are my age, 15.

We earn 300 to 500 pesos (US$7-11) every day. It's good pay. We sell the gold at the stores, and they buy it. I go individually to sell it [not in a group]…. We would pan and pan and put in the mercury at some point. We put the mercury in the pan and squeeze out the water, and what comes out is the amalgam.... We cook the amalgam. They have a blowtorch and we give air to the fire. And we hold the torch and direct it at the amalgam in the pot, and give it more air by pumping with my foot…. I'm the one who does the cooking. I do this three times a week. At the end of the day, we sell it. But, sometimes, we don't have enough gold so we wait until the next day.

I get the mercury at the store. I pay 25 pesos ($0.56) for the mercury…. The buyer gives us the mercury to use, and then subtracts the 25 pesos from the gold at the end…. Some of us, especially when it rains, we turn pale and we shake. It's been happening for quite some time. It happens to me and also to my friends. It may be from the cold. We call it "pasma" - it's like a spasm….

Mostly it's my hands, but sometimes it's my legs. And sometimes my whole body. It happens two days out of the three days I work at the mine. I feel like this a lot when we're at the site in the creek and we're wet. Often I get a fever from the work because I get tired…. Often I will just lie down. I can't stand up….

Each time that happens, I just tell myself I have to do this work to support my family because my grandmother can't work. I started working with mercury when I was 8 years old. The spasms started when I was 9 and have gone on until now….

I don't particularly like the work, but I have no choice. Our daily living depends on it. [112]

“Albert,” 16

I started at the mine when I was 12. I detach the box, the wooden box, from the pit for us to be able to transfer it to another pit. I also break piles of mud, sand, and rocks using my feet. Sometimes I do the compressor mining underwater…. I’m the one to shovel rocks and sand underwater for us to detach the wooden box and transfer it to another pit. I also go underwater to get gold. [I breathe] using the air compressor. I bite the hose and breathe from it. It’s the same as when you’re breathing above the water…. I go nine feet [nearly three meters] deep. I stay under about an hour….

Two people already died because of an accident. They got trapped. The pit collapsed. It’s dangerous in the pit.… It was in 2013. They were adults.[113] One was from Paracale. They were working here in the pond. I wasn’t there but I heard about it….

I go to work every day. It depends, but usually it starts at 7 a.m. and ends at 4 p.m. I rest on Sundays. During the day, I rest during mealtimes….

I use mercury. I actually cook the gold here before selling it to the trader…. I don’t go to school anymore. I studied until 6th grade but I didn’t finish. I’d like to go back…. I get romborombo [a skin condition]. It’s from the mud and the dirt. It lasts about three days. It’s itchy and it burns. I don’t go to the doctor. I treat it with tetracycline [an antibiotic].[114]

“Joseph,” 16

I started working when I was 12. Sometimes I help pull out the bags, and sometimes I go underwater. It’s just like digging with a shovel, and putting it in a sand bag.

[To breathe] I use the compressor. Just like what the others do. I bite the hose and release it whenever I need air, inhale, and exhale through my nose. It’s not hard to breathe…. At first, it was hard to think about going down… I don’t use goggles. I basically don’t use my eyes. I use my hands to look for the passage, the canal….

You don’t necessarily have to come up slowly. Sometimes you need to go up slowly, but not always. Sometimes you have to make it up fast, especially if you have no air in your hose if the machine stops working. It’s a normal thing [for the compressor to stop working]. It’s happened to me.

It [underwater mining] takes me one to three hours. I was 14 the first time I went under. Nobody taught me how to do it.

I go here at 7 a.m. and go back home about 3 or 4 in the afternoon. I work if there’s no classes. I work on Saturday and Sunday. Today [Friday] because it’s raining, I didn’t go to school…. I’m in my 4th year of high school. In a week, I skip one or a couple of days of school.

This particular site is owned by the barangay. It’s an old fish pond converted to a mining site. Everyone can come and work here as long as you are a resident.…

I get a skin disease. It’s not itchy, and it doesn’t hurt. But the color of the skin changes. It gets red. I get it on my face….

I can smell [the fumes from the compressor] when they are transferring fuel. I can smell it because it travels down the hose…. If I work so hard underwater, I get tired.[115]

“Jacob,” age 17

When I wake up in the morning at 7.30 I take my breakfast, then come here to start work in the tunnel. I go in the tunnel to take out the ore…. I climb out at noon to have lunch and back again at 1 p.m. At around 6 p.m., we get out to have dinner at 7 p.m., go back, and out again at midnight to have snacks, then afterward go back down again. We end our work in the morning. We rest 24 hours after we get off in the morning. Then we go back to work again doing the same thing after 24 hours of rest….

I am anemic now. When you’re anemic, you’re not supposed to miss sleep…. I often couldn’t take the sleeplessness. I would doze off even while working…. It’s hot inside, especially if the blower is turned off…. When there’s no blower, that’s when what we call “poison” happens, when we don’t have enough oxygen. If it’s turned off, we catch our breath all the time. Even when you sit there doing nothing, you will sweat profusely.

Also, inside, you can’t help thinking what if this collapses? It can be scary. Down there, you should be mindful of the rocks on the walls of the tunnel and you should check the timber support closely….

The first time I went inside, I was 14 years old. I was scared. I kept thinking what would happen to me if something went wrong. I would freak out each time, for example, a small stone hit me. When I used the hammer the first time to loosen the ore, I hit my arm. I often suffered cuts…. It swelled. It was a big hammer. I rested for a week after that.[116]

“Hernando,” 9

I am in grade 3 in Panique elementary school…. I get stones at the tunnel and then carry them to the ball mill…. I am coming on weekends and during holidays. I work with my older brother. My mum sells food here…. I earn about 900 pesos ($20) a month, someone at the ball mill gives me this money.[117]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched by Juliane Kippenberg, associate director in the Children’s Rights division of Human Rights Watch, Margaret Wurth, researcher in the Children’s Rights division, and Carlos Conde, researcher in the Asia division. It was written by Juliane Kippenberg.

The report was reviewed by Carlos Conde; Margaret Wurth; Jane Cohen, senior researcher in the Health and Human Rights division; and Chris Albin-Lackey, associate director in the Business and Human Rights division. Bede Sheppard, deputy director in the Children’s Rights division, edited the report. James Ross, legal and policy director, provided legal review. Danielle Haas, senior program editor, provided program review.

Production assistance was provided by Helen Griffiths, associate in the Children’s Rights division; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

We would like to thank the many organizations and individuals that provided input and support, in particular the Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research (EILER).