Toxic Toil

Child Labor and Mercury Exposure in Tanzania’s Small-Scale Gold Mines

Map of Gold Mining in Tanzania

Key Terms

|

Amalgamation |

The process of mixing and merging ground gold ore and mercury |

|

Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining |

Small groups of people engaged in low-cost, low-tech, labor-intensive excavation and processing of gold |

|

Biomonitoring |

The process of measuring human exposure to chemicals |

|

Due diligence |

The process of evaluating details before making a business decision; the care a person or organization takes to avoid harm |

|

Formalization |

The licensing and regulation of small-scale gold mining |

|

Licensed mine |

A legal, formal, small-scale mine with an owner who holds a Primary Mining License |

|

Mercury abatement |

The process of reducing mercury use and exposure |

|

Mercury intoxication |

Poisoning caused by mercury |

|

Methylmercury |

A toxic compound of mercury that tends to accumulate in fish |

|

Ore |

A naturally occurring material from which a metal or other valuable mineral can be extracted |

|

Orphan |

A child that has lost one or both parents |

|

Primary Mining License |

A mining license authorizing Tanzanian citizens and specific corporations to mine an area of 10 hectares for 7 years |

|

Retort |

A device that captures harmful mercury vapor |

|

Unlicensed mine |

An illegal, informal, small-scale mine that operates without a Primary Mining License |

Summary

Rahim T. is a small, soft-spoken, 13-year-old boy who lives with his aunt in a village in Chunya district in southern Tanzania. His father died and his mother lives in a larger town in the same district. Rahim T. started to working on mining sites over the weekends and during the school holidays, around the age of 11, because he was sometimes left at home alone without enough money or food to eat. He told Human Rights Watch, “My parents were not present at home. I saw my friends going there. I was hungry and in need of money so I decided to go there.”

Rahim T. uses mercury, a highly toxic silvery liquid metal, to extract the gold at home. He mixes roughly half a tablespoon of mercury with ground gold ore. He then stands a few meters away from an open flame where he burns the gold-mercury amalgam on a soda cap for about 15 minutes, releasing dangerous mercury vapor into the environment. Until our interview, no one had ever told him mercury can cause serious ill-health, including brain damage, and even death.

Soon after Rahim T. started mining, he was involved in a pit accident:

I was digging with my colleague. I entered into a short pit. When I was digging he told me to come out, and when I was about to come out, the shaft collapsed on me, reaching the level of my chest … they started rescuing me by digging the pit and sent me to Chunya hospital.

The accident, Rahim T. told Human Rights Watch, knocked him unconscious and caused internal injuries. He remained in the hospital for about a week and still occasionally feels pain in his waist when he sits. After the accident, he was scared of returning to the pits, but he felt he had no choice, explaining: “Whenever my aunt travels is when I go, because I need something to sustain myself.”

*****

Mining, the type of work described by Rahim T., is one of the most hazardous forms of child labor. Thousands of children in Tanzania, some as young as eight years old, risk serious injury and even death from work in this industry. Many children, especially orphans, lack basic necessities such as food, clothing, and shelter, and seek employment to support themselves and their relatives.

This report examines child labor and exposure to mercury in small-scale gold mining in Tanzania, Africa’s fourth-largest gold producer. It documents the harmful effects of mining on children, including its impact on the enjoyment of their rights to health, education, and protection from violence and abuse. The report focuses on hard rock mining, whereby small-scale miners remove and process rocks from pits to extract the ore. Human Rights Watch conducted research in Chunya district (southern Tanzania), in Geita and Kahama districts (northwestern Tanzania), and in the cities of Dar es Salaam, Mwanza, and Mbeya.

Small-scale gold mining is labor-intensive and requires little technology. Mining operations in Tanzania typically involve people who control the mine, pit holders (who lease pits from the people who control the mine), and workers, including children.

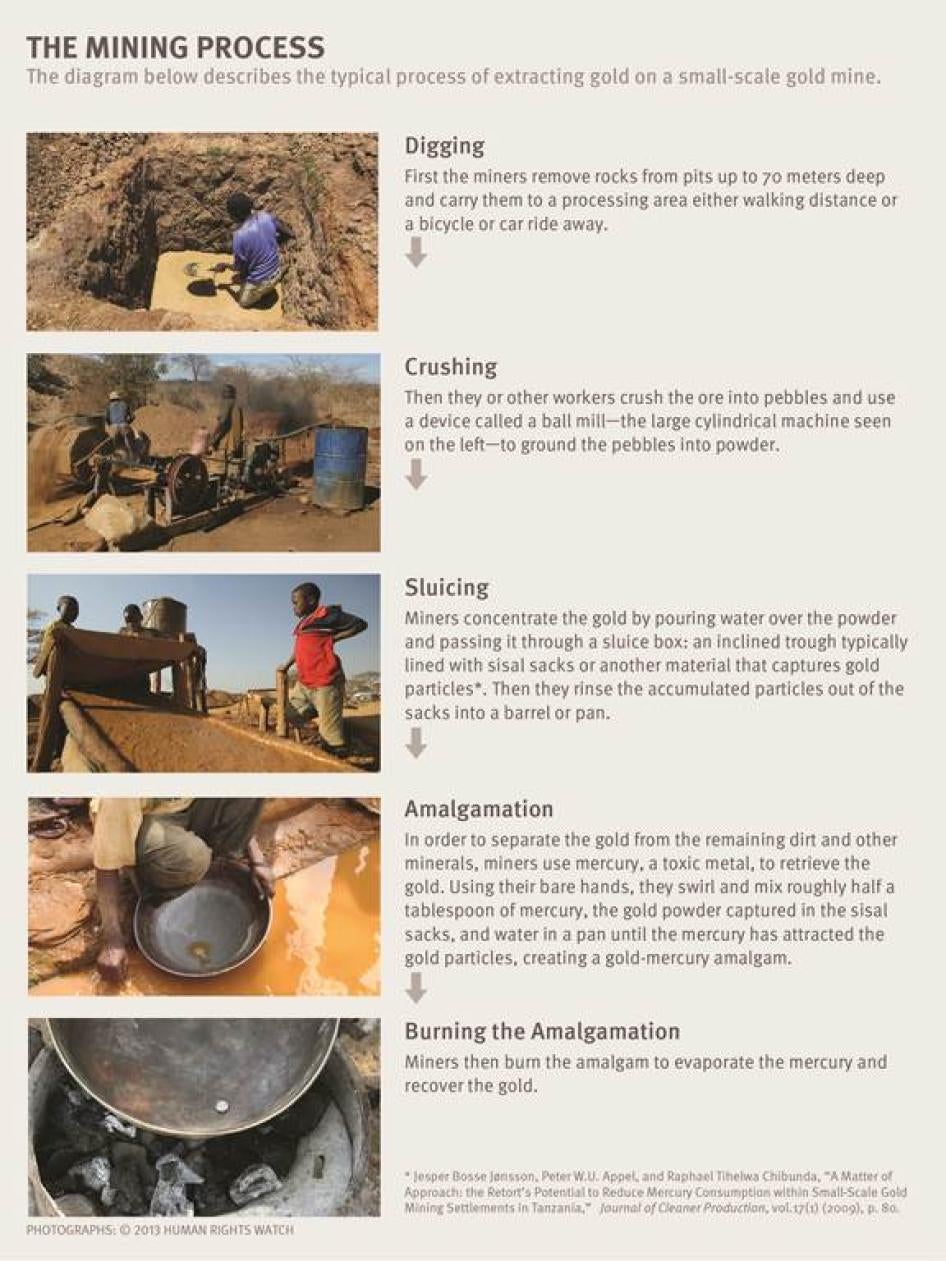

Children are involved in every phase of the mining process. They dig and drill in deep, unstable pits during shifts of up to 24 hours. They transport heavy bags of gold ore and crush the ore into powder. After concentrating the gold further, children mix the powder with mercury and water in a pan. The mercury attracts the gold particles, creating a gold-mercury amalgam. Children burn the amalgam to evaporate the mercury and recover the gold. Children who work in mining are exposed to serious health risks, including: accidents in deep pits, injuries from dangerous tools, respiratory diseases, and musculoskeletal problems.

Mercury poses a threat to children and adults who work in mining, as well as to surrounding communities. Miners, including children, risk mercury poisoning from touching the mercury and breathing the mercury vapor. People who live in mining areas may also be exposed to mercury when community or family members process the gold at home, or from eating mercury-contaminated fish from nearby rivers. Mercury attacks the central nervous system and can cause developmental and neurological problems. It is particularly dangerous to fetuses and infants, because their young bodies are still developing. Most adult and child miners are unaware of the grave health risks connected to the use of mercury.

Girls on and around mining sites in Chunya and Kahama districts face sexual harassment, including pressure to engage in sex work. As a result, some girls become victims of commercial sexual exploitation and risk contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Children who work in mining sometimes miss out on important educational opportunities and experiences. In some cases, mining causes children to skip classes or drop out of school. It can also impact students’ time and motivation for study.

This report also examines how gold traders may contribute to child labor in mining. Small traders purchase gold directly at the mines or in mining towns—including from children—and sell it to larger traders. Sometimes the gold passes through several intermediaries before reaching the largest traders who export gold. The top destination for artisanal gold from Tanzania is the United Arab Emirates (UAE); gold is also exported to Switzerland, South Africa, China, and the United Kingdom.

Under international and domestic law, the Tanzanian government is obligated to protect children from violations of their rights, including the worst forms of child labor such as mining and commercial sexual exploitation. Tanzania should provide free primary education and make secondary education, including vocational training, available and accessible. The government should also take measures to avoid occupational accidents and diseases, and reduce the population’s exposure to harmful substances. Scientific evidence shows that mercury is a harmful substance.

While the Tanzanian government has taken some important steps to reduce child labor and mercury exposure in gold mining, it has failed to adequately enforce its child labor laws and address some of the socioeconomic problems contributing to child labor.

In June 2009, the Tanzanian government launched the National Action Plan for the Elimination of Child Labour. Under its mining, child protection, and employment laws, the government also prohibits children under the age of 18 from engaging in hazardous work, including mining. Occasionally government officials inspect mines for child labor.

Despite these positive actions, the government’s 2009 child labor action plan remains unimplemented, its child labor inspection process is flawed, and key ministries are failing to prioritize and devote resources to enforce child labor laws.

The Ministry of Labour and Employment is the lead ministry on child labor, but it has taken limited action to counter child labor in mining. Its labor officers rarely, if ever, visit licensed small-scale mines for child labor inspections, and virtually never conduct child labor inspections on unlicensed, informal mines—the majority of sites. The Ministry of Energy and Minerals is also failing to carry out its responsibilities under the mining regulations, which authorize mining officials to order mining license holders who have hired children to pay a fine or take remedial action. Both ministries lack adequate staff and means to visit remote mining areas. When labor or mining officials did carry out child labor inspections, they sent younger-looking children away from the mines, but did not properly assess the ages of older children or follow up to support the children’s transition out of child labor. Mining officials often prioritized revenue collection and other health and safety issues over child labor when visiting licensed and unlicensed mines. Both ministries seldom penalized employers who hired children.

The government has also failed to adequately address some of the underlying socioeconomic causes of child labor. In particular, the government provides too little support to orphans and other vulnerable children, many of whom seek employment in mining to cover their basic needs. Moreover, weaknesses in the education system indirectly contribute to child labor. In particular, despite the official abolition of school fees through the 2002-2006 Education Development Plan, schools sometimes request illegal financial contributions, prompting students whose parents are unable to pay such expenses to either seek additional income on the mines or to drop out of school. Also, many children across Tanzania do no transition from primary to secondary or vocational school and start full-time work in sectors such as mining. This is partly because of the cost of attending secondary school and limited vocational training opportunities.

The threat of mercury is recognized by Tanzania, but its use in small-scale mining continues unabated. Tanzania has laws and institutions in place to regulate the mercury trade and promote safer mercury use in mining. In 2009 the government developed a National Strategic Plan for Mercury Management, which includes strategies to raise awareness on the hazards of mercury and introduce mercury-free technology to extract gold. Under the mining regulations, an owner of a licensed mine must use a retort—a device that captures harmful mercury vapor—and provide employees with protective gear. The government also requires those who intend to import, export, transport, store, and deal in chemicals to register specified quantities of mercury with the Chief Government Chemist. By controlling the flow and use of mercury in the country, the government can incentivize miners to explore alternative gold extraction methods.

However, the government has done little to put these laws and policies into action. It almost never enforces the regulations that require the registration of mercury for small-scale gold mining or the use of retorts and protective gear on mining sites. It has also failed to launch the Mercury Management Plan and to devise a health sector response to mercury poisoning.

Donors, United Nations agencies, international financial institutions, and civil society organizations play an important role in assisting poorer nations to fulfill their obligations under international law. These groups have taken some steps to support initiatives on child labor, mercury use, and mining generally, but only a handful of donor initiatives specifically address child labor or mercury use in small-scale gold mining. Some programs, such as the World Bank’s Sustainable Management of Mineral Resources Project (SMMRP), which supports Tanzania’s small-scale miners, could potentially do more to target child labor in small-scale gold mining.

Businesses, under international law and other norms, also have a responsibility to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for the impact of their activities on human rights, and to adequately address abuses connected to their operations. Gold traders in Tanzania who were interviewed for this report lacked specific due diligence procedures to avoid supporting unlawful child labor. Meanwhile, international standards for human rights due diligence have largely focused on due diligence for “conflict gold”—gold which benefits conflict parties and hence contributes to armed conflict. As a result, companies have done less to prevent supply chains from becoming entangled with suppliers who exploit unlawful child labor.

Ending child labor in gold mining requires the government, UN agencies, donors, artisanal miners, gold traders, and companies to prioritize and fully support its elimination. Failure to act places children at risk of serious injury or death and may destroy their educational opportunities. Additionally, failure to limit the use of mercury may cause devastating health and environmental effects for both children and adults.

Key Recommendations

To the Tanzanian Government

Child Labor

- Instruct mining and labor officials to regularly inspect and withdraw children from mining work on licensed mines and impose penalties on those who employ child labor. Government measures must respect human rights and should not lead to retribution or severe punishments;

- Instruct labor officers to inspect unlicensed mines. If mining officials informally visit an unlicensed mine, they should remind employers of child labor laws, encourage them to comply, and request the Ministry of Labour and Employment to conduct further inspections and, where necessary, impose penalties;

- Instruct labor officers, social welfare officers, and parasocial workers to identify and protect girls who work in mining from sexual abuse;

- Conduct awareness-raising and outreach activities on the hazards of child labor in mining;

- Support orphans and other vulnerable children by, for example, implementing the National Costed Action Plan on the Most Vulnerable Children and expanding the Tanzania Social Action Fund which provides grants and conditional cash transfers to vulnerable populations;

- Instruct district officers to investigate and eliminate illegal primary school fees to ensure they do not thwart access to education in mining areas;

- Increase access to post-primary education in mining areas by allowing children to retake the Primary School Leaving Examination and compete for a place at a secondary school and by increasing opportunities for vocational training;

- Strengthen and intensify efforts to formalize the artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector without engaging in a mass clampdown on unlicensed mining activity;

- Explicitly address child labor and mercury exposure in current efforts to promote the development and professionalization of artisanal mining, including through the government-led Strategy to Support Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Development and the Multi-Stakeholder Partnership between the government, World Bank, Anglo-Gold Ashanti, and African Barrick Gold.

Mercury Exposure

- Urge an immediate end to mercury use by anyone under age 18 as part of broader efforts to raise awareness and enforce safe mining practices and to promote mercury-free alternatives;

- Develop a health response to address mercury exposure and poisoning in artisanal mining communities, with a focus on child health, including by revising and launching the National Strategic Plan on Mercury Management.

To Donor Countries, the World Bank, and Relevant UN Agencies

- Provide financial, political, and technical assistance to address child labor and mercury exposure in mining, including through programs on artisanal mining.

To Tanzanian and International Companies Trading in Artisanal Gold

- National and international companies buying gold from Tanzania’s small-scale gold mines should have due diligence procedures in place to ensure that their supply chains are free from child labor. If child labor is found, companies should work with their suppliers to end child labor in the supply chain within a defined timeframe and cease working with suppliers who are unable or unwilling to comply.

Methodology

This report examines child labor and mercury exposure in small-scale gold mining in Tanzania. It documents the harmful effects of mining on children, including its impact on the enjoyment of their rights to health, education, and protection from violence and abuse. It focuses on hard rock mining, whereby small-scale miners remove and process rocks from pits to extract the ore.

Human Rights Watch chose to focus on Tanzania because it is one of Africa’s largest gold producers and it has a substantial small-scale gold mining community. Despite previous interventions by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), child labor and mercury use are still prevalent in small-scale gold mining in Tanzania.

Human Rights Watch conducted research in October and December 2012 in mining areas in northwestern and southern Tanzania, and in the cities of Dar es Salaam, Mwanza, and Mbeya. Tanzania has roughly 12 gold mining regions and researchers visited 11 mining sites in 3 of these areas: Geita district (Geita region), Kahama district (Shinyanga region), and Chunya district (Mbeya region) (see map). Human Rights Watch focused on these areas because of their geographic diversity and large artisanal gold mining communities.

Human Rights Watch interviewed over 200 people, including 80 children between the ages of 8 and 17 working in artisanal gold mining areas. Of these 80 children, 61 were directly involved in the gold mining process (48 boys and 13 girls). Another 13 (7 boys and 6 girls) did other jobs on the mines such as selling wood, food, water, and coal; and six girls engaged in sex work near the mines. Researchers also spoke to four young adults between the ages of 18 and 20 who were working in gold mining. At least 20 of the children interviewed were orphans. Human Rights Watch selected the children who work in mining randomly on the mining site or at a nearby school. A nongovernmental organization (NGO) helped researchers to identify children engaged in sex work near the mines.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a wide range of other individuals in mining areas, including parents and guardians of child laborers, adult miners, representatives of regional miners’ associations, teachers and principals, health workers and health experts, village authorities, local government officials, NGO activists, and gold traders. In addition, Human Rights Watch researchers met with representatives of United Nations agencies, donor governments, and a large-scale mining company.

Researchers interviewed representatives of the Ministry of Labour and Employment, the Ministry of Energy and Minerals, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (specifically the Social Welfare Department and the Government Chemist Laboratory Agency),the Ministry of Community Development, Gender, and Children, and the Environmental Division of the Vice President’s Office. Outside of Tanzania, Human Rights Watch interviewed several international experts on small-scale gold mining, mercury use, and the health effects of mercury. Researchers also met with gold trading and refining companies in Switzerland and Dubai. No inducement was offered to or solicited by the interviewees.

Where possible, Human Rights Watch carried out interviews with children in a quiet setting, somewhere near the mining site or in a school classroom, without others present. All children were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways the information would be used. Each orally consented to the interview. Because of the difficulty of maintaining privacy on large mining sites, some interviews were conducted in the presence of a few adult miners and other children. Researchers interviewed the girls engaged in sex work in small focus groups in Mbeya and Chunya town. Human Rights Watch adapted the length of the interview and complexity of the questions to the age and maturity of each child. Interviews with children under the age of 10 did not last longer than 20 minutes, while those with older children took up to 90 minutes. The interviews were semi-structured, and not all children were asked the same questions.

In addition to these interviews, Human Rights Watch carried out desk research, consulting a wide array of written documents from the Tanzanian government, UN agencies, NGOs, media, academia, privately owned international companies, and other sources.

In this report, “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law. The names of all children have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their privacy and to preclude any potential retaliation. In several instances Human Rights Watch has also withheld the name of some adult interviewees for security reasons.

Most interviews were conducted in Swahili, the main language of Tanzania, through the help of an interpreter. Some of the interviews in Kahama district were conducted in Sukuma.

One challenge during this research was the assessment of children’s ages. Some children did not know their exact age. Researchers only classified interviewees as children when this was clearly indicated by the interviewees’ own assessment and physical appearance.

I. Background: Artisanal Gold Mining, Mercury Use, and Child Labor in Tanzania

Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in Tanzania

“Artisanal” and “small-scale” gold mining refers to small groups engaged in low-cost, low-tech, labor-intensive excavation and processing of gold.[1] According to the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), the global artisanal gold mining sector produces an estimated 15 percent of the world’s gold (approximately 400 tonnes) and employs 90 percent of the global gold mining workforce—around 10 to 15 million miners, including children.[2]

In 2011, Tanzania was the fourth largest gold producer in Africa.[3] Roughly 5 percent of Tanzania’s gross domestic product and one-third of its exports come from mining.[4] Experts estimate that around 10 percent of the country’s gold comes from small-scale mining, a number which continues to grow in response to rising gold prices and limited alternative sources of income.[5] The remainder of the gold is produced by medium and large-scale mining companies. In 2011, Tanzania earned US$2.1 billion in mineral exports, of which more than 95 percent came from six gold mines.[6] According to government figures, there are more than 800,000 small-scale gold miners,[7] thousands of whom are children.[8]

Despite Tanzania’s gold wealth, the country is poor. The 2011 Human Development Index, which measures health, education, and income, ranked Tanzania as 152ND out of 187 countries.[9] About 67.9 percent of the population lives below the international poverty line of US$1.25 per day.[10]

The Mining Process

In hard rock mining, the focus of this report, small-scale miners remove the rocks from pits and process them on the mining site, in processing areas, or at home, to extract the ore.[11]

Small-scale gold mining occurs both illegally and with government sanction in Tanzania. To mine legally, Tanzanian citizens must apply for a renewable Primary Mining License (PML) authorizing them to mine an area of 10 hectares for 7 years.[12] Citizens can apply for multiple licenses. The mining regulations, Law of the Child Act, and Employment and Labour Relations Act prohibit license holders from employing anyone under the age of 18.[13] Once the PML is issued, the owner is legally responsible for activities on the site, including compliance with mining, environmental, and safety regulations.[14]

However, the majority of small-scale mining takes place on unlicensed, unauthorized mines.[15] Some unlicensed mines exist for many years and are usually controlled by the land owner or a prominent community member.[16] Other “gold rushes” spring up quickly and exist for a few months, typically on land owned by another individual or mining company.[17] Communities rush to these areas when there is news of someone striking gold and settle there until the deposit depletes or until they are evicted by local authorities.[18]

Currently, few individuals are able to apply for a PML because large mining companies hold prospecting and mining licenses over much of Tanzania’s mineral-rich areas.[19] Additionally, applying for a PML may require overcoming significant costs and bureaucratic hurdles. At present a PML costs 20,000 Tanzanian Shillings (T Sh) (US$12.28).[20] According to one researcher, miners may also have to pay other hidden expenses such as the cost of finding the coordinates of a mining area or a $50 fee to access information from a database at the Zonal Mines Office about the location of other mining licenses.[21] Small-scale miners may also lack knowledge of the legal requirements and institutional procedures to apply for a PML.[22]

The government recently commenced a process to make licenses more accessible to small-scale miners by negotiating for land with large-scale mining companies and by cordoning off some relinquished land from prospective license holders.[23]

There are up to three hierarchical categories of labor on small-scale gold mines: the person who controls the mine (a PML holder, land owner, or prominent community member, who is commonly called the “owner”), pit holders (who lease pits from the person who controls the mine) and workers (who dig in the pits, and who may also engage in other processing activities).[24] Most mines operate using a production-sharing model, meaning the owner, pit holder, and workers each take a percentage of the ore or gold produced.[25] Typically the owner claims between 20 and 50 percent of the gold production.[26] Once the miners dig up the ore from the pits, specialized workers sometimes process the gold. Their activities include ore transportation and crushing, as well as separation of the gold through mixing with mercury.[27] They typically receive payment in the form of a fixed amount of cash or ore.[28]Children are involved in both digging in the pits as well as processing activities.

Mercury Use in Gold Mining

The use of mercury to extract gold in hard rock mining is widespread. While large mining operations have the capacity to use cyanide for more complex and efficient processing, poorer small-scale miners in some 70 countries, including Tanzania, rely on mercury to extract the gold.[29] They mix the crushed gold ore with the mercury and heat the amalgam to evaporate the mercury, leaving gold behind. Evaporated mercury can travel long distances, even between continents, and can impact areas far away from small-scale mines.[30] According to the expert database Mercury Watch, Tanzania is the third highest mercury emitter in Africa after Ghana and Sudan, releasing an average of 45 tonnes of mercury in 2010.[31]

Small-scale miners favor mercury over other forms of extraction because of its ease, affordability and accessibility.[32] It allows miners to work efficiently and independently.[33] Current mercury-free extraction alternatives are more difficult to introduce because of their cost, training, and organizational requirements.[34]

Child Labor in Tanzania

Child labor is a problem in mining and across many other sectors in Tanzania, including in agriculture, domestic work, and fishing. Agriculture employs close to 80 percent of Tanzania’s rural labor force and the greatest number of children.[35] According to a 2006 government survey, about 20 percent of children between the ages of 5 and 17 are engaged in some form of child labor in Tanzania, though this number may be higher, because of the definition of child labor used in the research.[36]

The International Labour Organization (ILO) considers mining among the most hazardous sectors and occupations, because of the rates of death, injury and disease in the sector.[37] Although the Law of the Child Act, Employment and Labour Relations Act, and the mining regulations prohibit mine owners from employing children, the United Nations and NGOs have documented the use of child labor in tanzanite gem mines and in small-scale gold mining.[38] Thousands of children are likely to be involved in this sector.[39] The government has also adopted a list of hazardous work, under the regulations of the Law of the Child Act, which names and prohibits many forms of labor including small-scale mining and commercial sexual exploitation.[40]

Poverty drives many children to seek employment in mining.[41] Most of the child laborers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they used their earnings for basic necessities such as food, rent, clothes, and school supplies such as exercise books, pens, and uniforms.

Children who have lost one or both of their parents—orphans—are particularly likely to be involved in the worst forms of child labor.[42] Tanzania has an estimated 3 million orphans, of whom roughly 1.3 million have lost a parent due to AIDS.[43] Many of these children lack financial and other support from their guardians or extended families.[44] Other factors, such as the gender, health status, and remarriage of the surviving parent or caregiver, may also contribute to orphans’ vulnerability to child labor.[45] A 2002 ILO study found that roughly 53.8 percent of children engaged in fulltime work in Tanzania were either orphans or came from families where the father was absent or had died.[46]

II. “I Fear a Lot”: Child Labor and Exposure to Mercury in Small-Scale Gold Mines

The Hazards of Mining Gold

Children work long hours, in hazardous conditions, on unlicensed and licensed small-scale gold mines, despite the prohibition of this type of work in Tanzania’s employment, mining, and child protection laws. Mining activities, such as digging and drilling in pits, working underground, crushing ore, and using mercury to extract the gold, expose children to many physical dangers, including dangerous tools, unstable pits, and toxic gases.

Interviewees suffered from fatigue, headaches, muscular pain, blistering, and swelling. Research suggests that long-term problems might include respiratory diseases, musculoskeletal problems, and mercury poisoning. Children often contributed some or all of their earnings to their families or relatives. Human Rights Watch interviewed girls who work on or near mining sites and found they sometimes became victims of sexual exploitation and abuse. Child labor in artisanal mining also affects school attendance and performance, and can cause children to drop out of school entirely.

Physical Dangers of Mining Gold

Digging and Drilling Pits

The first phase of small-scale gold mining involves manually digging pits ranging from a few meters to up to 70 meters deep.[47] Human Rights Watch interviewed 18 children (14 boys and 4 girls) in Geita, Kahama, and Chunya districts, who dug in pits—a task that is especially common on new sites. For example, Issa M., about 12 years old, told Human Rights Watch that he dug the rocks with a pick, adding “It’s hard work. It’s hard rock. It’s hard to break. Yesterday was the first day I did it. My hands are aching.”[48] An 11-year-old boy, Jalil H. said, “When I was digging one of the rocks, the rock hit [my hand]. There is a scar. I found a piece of cloth to cover it and continued. My hand is aching.”[49]

While most children dug with shovels, hammers, and picks, a few said they used drills. This tool is particularly dangerous because it is heavy and flings stones into the surrounding area. Thirteen-year-old Michael H. described losing control of the drill for a moment:

I was hurt from the instrument I use to dig. I was drilling. I was sent to hospital. I hurt a toe. The whole nail was peeled off. I took medicine. When I was drilling I drilled on the stone and then the instrument lost direction and landed on my foot…. I was 12 [when the accident happened].[50]

Prolonged exposure to dust from drilling operations and handling and crushing ore may cause lung diseases such as silicosis.[51] Miners with silicosis are at a high risk of developing tuberculosis (TB).[52] The severity of childhood pulmonary TB is not well understood because it is difficult to diagnose and limited information is known about the outcomes of children with TB.[53]

Working Underground

Work underground in unstable pits is one of the most hazardous aspects of mining. The Mining Regulations require adult miners to ascend and descend on a ladder on one side of the pit and to hoist the minerals retrieved in the mine on the other side.[54] However, children use a range of dangerous techniques to climb down deep pits to dig and collect ore, risking injury and even death from falling. Several boys told Human Rights Watch that they climbed down the pits by either holding onto the sides of the pit or onto a rope. Fumo D., who was 15 years old, stated:

We go down the pit by holding onto the sides [with the right and left foot]. The pits are 8 to 10 meters deep, even 15 meters…. Several people go down to different levels. We hoist the ore up, passing the sacks from person to person…. Sometimes we use ropes, tied to a tree.[55]

These dangerous climbing techniques have sometimes resulted in children falling. Fumo D. also told Human Rights Watch: “One of the students, Anthony D., slipped and had a fracture. He was treated in Geita. He was in class 4, 11 or 12 years old.”[56] Bakari J., a 16-year-old boy, said: “Last week I slipped in the pit when I was climbing up. I fell. I hurt my elbow.”[57]

Two children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were involved in accidents where the pits collapsed. Adam K., a 17-year-old boy shared his harrowing experience:

One time the pit collapsed. It was September last year. I thought I was dead, I was so frightened. I was digging down and I went horizontally and then the rest of the land slid. I was just behind the landslide, not inside. Two of my friends [both adults] who were on the other side died. I was so scared. I just cried and despaired.[58]

A pit also collapsed on 13-year-old Rahim T. in Chunya district. Fellow miners nearby had to dig him out of the pit and he spent about a week in the hospital.[59]

Medical officials in Geita and Chunya districts described attending to fractures, broken bones, and cuts from mining accidents, particularly from collapsed pits.[60]

Children who work in deep pits may be exposed to dangerous and sometimes deadly gases that may be released during the mining process.[61] This includes gas from pumps, which the government prohibits underground, but which miners often use to remove water from the pits.[62] In order to mitigate the dangerous effects of the gas, 15-year-old Fumo D., who mined in Geita district explained, “We throw branches when there is gas [to increase the oxygen levels in the pits]. We sense this when we are going down into the pit. Near the ground, you feel how your chest tightens.”[63]

Medical officials in Matundasi Ward in Chunya district and one child miner reported seeing a total of five adult deaths caused by gas from the mines.[64] A medical official working near the mines in Chunya told Human Rights Watch:

We see that the most dangerous are gas accidents because when they [the miners] are drilling they use those chemicals and gases to drill … When they feel like the gold is already maybe near, they just go down before the gases are finished [have escaped into the atmosphere].[65]

Carrying and Crushing Gold Ore

After miners retrieve gold ore from the pits, they carry the rocks to a processing area where they or other workers crush the ore into powder. Transport of ore is a common form of work for boys and girls on the artisanal gold mines.

Sacks of ore can weigh up to 60 kilograms and can cause potentially serious injuries.[66]

Abasi L., who worked in Geita district, said he transported ore for the first time at age 16. Once he carried a load that was too heavy for him over a distance of roughly 15 meters. He started feeling pain in his chest and had to be hospitalized. It took him three days to recover.[67] Even small children haul heavy loads. Faraji J., a boy about 8 years old, told Human Rights Watch: “I help my mum by collecting stones [ore]. I carry the stones in bags on a bicycle. I bring them to the crusher. I don’t like the work.”[68] Lifting and carrying heavy ore can lead to skeletal deformation and accelerated joint deterioration.[69]

Miners first crush the ore manually using hammers, stones, and other metallic objects. Eight children we spoke to said they had accidentally hit their hands while crushing the ore and two had lost fingernails. Akilah O., a 10-year-old girl, explained:

[I] once knocked till my nail was removed. I was taken to a hospital and they put a bandage…. I was seven years old. It was a hammer that hit me…. [I am] scared a lot, nowadays I do not prefer crushing, I do other processes.[70]

The miners also crush or further process the gold ore using a type of grinder called a ball mill—a large, cylindrical machine. One child laborer complained that sometimes the belt from the ball mill would hit his hands.[71]

After crushing the gold ore into dust, miners often concentrate the gold by pouring water over the ore and passing it through a sluice. They then rinse the accumulated particles and remaining dust out of the sacks in a barrel or pan.[72]

Mixing and Burning Mercury-Gold Amalgam

In order to separate the gold from the remaining dirt and other minerals, miners use mercury to retrieve the gold. Using roughly half a tablespoon of mercury for a pan of water and ground ore, miners mix the solution with their bare hands until the mercury has attracted the gold particles, creating a gold-mercury amalgam. They then burn the amalgam to evaporate the mercury and recover the gold. During this process, children may have direct contact with mercury by touching it with their bare hands and by breathing in fumes as the mercury is burned away, both of which places them at risk of mercury poisoning. Mercury can cause irreversible damage to a child’s development and a wide range of serious conditions.[73]

Michael H., a 13-year-old boy, described the amalgamation process to Human Rights Watch:

I take the ground sand and put it in a basin and I pour in water and put in a small amount of mercury.... Then I start mixing the sand with the mercury. When l finish, I take a piece of cloth [to squeeze the amalgam in the cloth to get rid of the water]…. When I finish filtering, I take the cloth out and … I find gold [the mercury-gold amalgam] … I take a certain bowl made of metal and I burn [the amalgam] … and it turns to gold. Sometimes I do it by myself. Sometimes I do it with my friends. After I burn, I take the gold when it cools.[74]

Nineteen children (seventeen boys and two girls) interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had used mercury on the mines. The youngest was 12 years old. He told us he accompanied his mother to the mine daily where he sometimes mixed the mercury and gold and burned the amalgam. He complained that he experienced dizziness and pain in his head every day.[75]

The most serious health hazard comes from exposure to mercury vapor.[76] After amalgamation, gold miners burn the amalgam on a small fire to recover the gold. Some children do this a few times per week. During the school holidays, 13-year-old Zaki S. said he mixed and burned the mercury gold amalgam up to twice a day; 13-year-old Rahim T. said he processed gold with mercury about three times per week.[77] Most children we interviewed said that they stood between one and three meters way from the amalgam as it burned. The length of time for burning is usually a few minutes, but it varies, depending on the quantity of gold.[78]

Exposure to mercury vapor occurs even when children do not burn the amalgam themselves. Some children, like 14-year-old Taji J., said they handed the amalgam to an adult who specialized in amalgamation—an “amalgamator”—or a trader, and watched it burn, adding: “The one who buys the gold is the one who burns it. I am always there when they burn it.”[79] The evaporated mercury can travel long distances, potentially impacting children near the burning site and many kilometers away.[80]

Despite widespread knowledge that mercury is dangerous, many interviewees did not know how it could affect their own health and had limited information about how they could protect themselves.[81] Some adult and child miners said they tried to avoid exposure to the mercury vapor by covering their noses, and by standing far away from the burning amalgam or in the opposite direction of the wind.[82] One adult interviewee told Human Rights Watch, “People drink tea with lots of milk to protect themselves.”[83]

Working Hours and Remuneration

Children described working long hours and earning money either through selling the gold they extracted or for discrete tasks on the mine. They often used their earnings to contribute to their family or other adults they lived with.

Working Hours

Most of the children we interviewed said they worked for long hours. Almost half were not enrolled in school and said they came to the mine several days per week, sometimes daily.[84] Their shifts on the mine lasted between 6 and 24 hours. Six said they worked late at night or early in the morning, in violation of the Law of the Child Act, which prohibits children from working between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m.[85] Asani A., a 17-year-old boy, described how he worked underground through the night, with a group of five to ten people in Geita district: “You enter in the morning and stay for around 24 hours, then you have a day of rest. Yesterday I was in the mine from 1 p.m. to 6 a.m.”[86] Musa N., a 15-year-old boy, also told Human Rights Watch about his 24 hour shift: “Some days I work day and night. I start my duty at 11 p.m. until 11 p.m. [the next day]. We divide into two groups so I can rest when the others are working.”[87]

Other children in Geita, Kahama and Chunya districts said they attended school but worked after school, over the weekend, and during the school holidays. Combining school and mining work may affect children’s education as it limits their time for study, reduces their eagerness to learn, and may impact their performance.[88]

Remuneration

Some child laborers said they earned money by processing and selling the gold they had extracted to traders; others said they were paid cash for specific tasks. The pay was not regular, as gold mining is unpredictable. Children reported selling 1 gram of gold for 50,000 to 70,000 Tanzanian Shillings (TSh) (US$30.70 - $42.98). Child laborers involved in processing earned between 1,000 and 5,000 TSh (about $0.61 - $3.07) for crushing a pile of rocks, 2,000 TSh (about $1.23) for mixing a basin of mercury and gold, and 1,000 to 20,000 TSh ($0.61 - $12.28) for a day’s work. Like adults, children who mined in a group normally shared the proceeds with their team and sometimes had to pay the owners of the mine or pit a portion of the gold or a percentage of the sale.[89] Children often used the income they earned to help to support their families or relatives they lived with.

Sexual Exploitation

Small-scale gold mining communities are largely made up of makeshift settlements of single, male migrants with some disposable income, contributing to high levels of sexual exploitation of children and adult sex work. Some girls on and around mining sites, including those working in small restaurants preparing food for the miners (a common job for girls at mines), reported sexual harassment, being pressured into having sex, and commercial sexual exploitation.[90] This places girls at heightened risk of sexual violence and transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Yasmin D, a 15-year-old girl who extracted and processed her own gold in Chunya, described the practice of men approaching girls on the site for sex:

A lot of men approach me … always showing me money…. Sex work is very common. [There are] many women coming from town…. I had a friend who is doing that. Most of those are working in the bar. Sometimes they stay here [on the mine] … they sacrifice themselves in the forest. They create a hut and stay.[91]

Two cousins, both girls, Eidi B., age 16, and Farida C., age 15, sold food on a gold rush site in Kahama district with their grandmother. They also described men harassing them on the site. Both girls were living on the mine with no running water to bathe or go to the toilet. Eidi B., told Human Rights Watch:

It’s a bad situation here. There are no latrines and no water for bathing…. I do not like it here. Men want to have relationships…. A guy came to the restaurant and said I want you to be my girlfriend and to make you laugh, because I love you … Later when I refused, he said I was foolish. There have been many other cases like this. Some come to buy you food or soft drinks…. I would like to go to Mwanza [the capital of the region] and get tuition to go to school there again.[92]

Six girls interviewed in Mbeya region had engaged in sex work near the mines. Some came to stay in guesthouses in mining towns for brief periods of time.[93] Others worked as barmaids in Chunya district in Mbeya region. The barmaids said they had no option but to engage in sex work because they did not receive regular pay.[94] Wanda S., age 14, explained, “Some bosses don’t give money for food [to eat]. If they don’t provide money for food, [you have to do sex work]…. I want to stop it…. I am regretting doing it [sex work].”[95]

Girls are also at risk of sexual violence. Medical officials at Chunya District Hospital said that they treated one victim of rape per month, including girls, mostly from small-scale gold mining areas in the district.[96] A 2013 baseline survey, conducted by Plan International on the eradication of the worst forms of child labor in eight mining districts, found that 19.2 percent of the working children surveyed were sexually abused.[97] Girls who are victims of commercial sexual exploitation are particularly vulnerable to rape and other forms of sexual violence, as are adult sex workers.[98] In Itumbi village in Chunya district, one sex worker complained they did not have an official place to report abuse from their clients.[99]

Girls who are sexually exploited are at risk of getting infected with HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. HIV prevalence among sex workers in Tanzania is significantly higher than the prevalence in the general population between ages 15 and 49, which is at 5.6 percent.[100] A 2003 study conducted in the mining regions of Geita and Shinyanga found that 41.8 percent of female food and recreational workers were infected with HIV or another sexually transmitted infection.[101] A study of female bar workers in Mbeya region found an even higher HIV prevalence rate of 68 percent.[102] Although condoms are sometimes sold in the bars in mining areas, some of the girls never used them. Ituri K., a 16-year-old girl engaged in sex work, told Human Rights Watch that she did not know about HIV and that she had never used a condom with any of the men she had sex with.[103] Some of the girls who used condoms with their clients still feared contracting sexually transmitted infections.[104]

Harm to Education

In some cases, child labor in mining affects children’s school performance and attendance and can cause them to drop out of school entirely.

Children told us they sometimes missed school to work in mining. Lila A., a 12-year old girl who lived in Kahama district explained, “When I come to the mine I never go to school on that day.”[105] Dahlia A., a 10-year-old orphan who lived with her grandparents, said her grandmother sometimes encouraged her to skip school so she could transport ore at the mine.[106] Teachers in mining towns complained of low attendance during mining season. A deputy head teacher from a primary school in Kahama district stated, “The children who work in the mine are not attending classes. Before mining started [in July], attendance was so high. Since mining started, attendance has been poor.”[107] Another teacher in Kahama district told Human Rights Watch that during a gold rush period in his town, he could see a visible difference in attendance.[108] Teachers in mining areas described incidents of students being absent for two days per week and sometimes even a month or two.[109]

Mining can also hurt children’s performance by limiting their time for study and by making them sick. Fumo D., a 15-year-old boy, stated:

It is difficult to combine mining and school. I don’t get time to go through tutoring [which takes places on the weekends]. It [mining] hampers my schooling because sometimes it makes me less good at school. I wonder about the mine, it distracts me…. One day I did not take the bath [after mining] and then I fell sick [and missed classes]. I had pain all over my body.[110]

Loss of motivation and time for studies can cause children to fall behind in school. One child laborer described how he thought he had failed an exam because he was mining.[111] A teacher in a mining village stated that students that missed school lagged behind academically.[112] A 2013 baseline survey conducted by Plan International for their project on the eradication of the worst forms of child labor in eight mining wards in Geita district similarly found that fatigue and sickness caused by work in various sectors contributed to absenteeism and reduced the children’s rates of concentration in class.[113]

Some government and education officials stated that small-scale mining contributed to dropouts. The district commissioner of Geita stated, “Boys leave schools and prefer going to the mine.... Children’s dropout [rate] is on the increase because of their involvement in mining.”[114] In a group interview, three teachers who work in Geita district explained that children are tempted to go to the mines when they see former classmates with cellphones and that mining is the main reason children drop out.[115]

Mercury Exposure and Effects on Children’s Health

Mercury use on small-scale gold mines poses a threat to artisanal miners as well as to surrounding communities.

The previous section describes how children who work in mining inhale toxic mercury vapor when burning the mercury-gold amalgam. They mix mercury and ground ore with their bare hands, creating a gold-mercury amalgam. They then burn the amalgam on a small fire to evaporate the mercury and recover the gold. The most serious health hazard comes from exposure to mercury vapor.[116] Some children in Chunya district processed the gold and mercury multiple times a week.

This section shows that even children who are not working with mercury are at risk of exposure. They may inhale mercury vapor or ingest mercury-contaminated dust when family or community members process gold at home. Also, mercury from mining sites can enter the environment and be transformed into a compound called methylmercury which may make its way into fish, posing risks to all fish-eating populations in the affected region. As a result, more children may be exposed to mercury in the home than through work in mining.

Mercury poisoning can cause a wide range of serious health effects for children. It attacks the central nervous system and can cause developmental and neurological problems. Mercury is particularly dangerous to fetuses and infants.

Mercury Exposure around Small-Scale Gold Mines

Burning Amalgam in Residential Areas

Miners sometimes process gold ore at home because of security concerns and scarcity of water on the mine. A study conducted by a local nongovernmental organization (NGO) on the impact of mercury use by small-scale gold miners found that “[d]ecomposition of gold-mercury amalgam is either done at home, in the bush, mining sites, processing sites or anywhere the miners feel that they are safe.”[117] This practice exposes children in these areas to toxic mercury vapor.

Human Rights Watch interviewed seven individuals who processed gold in their homes. Three were adult miners who regularly brought gold home. One of the miners lived with his wife and 4 children, ages 14, 12, 5, and 1, in a village in Chunya district.[118] He had a small outdoor area in the center of his compound where he had processed crushed gold daily since 2007. He kept some of the mercury-contaminated sandy remains in the center of the compound after amalgamation. Human Rights Watch found his one-year-old daughter playing in these remains. When the miner finished amalgamating the gold ore and mercury, he burned it in a spoon or bowl about two meters away from the entrance to the kitchen and a sleeping area. When asked whether he was ever afraid of his children inhaling the mercury vapor, he responded, “[There is] no way out … that is how we survive.”[119]

Human Rights Watch also visited a trader’s home in Chunya district where miners processed the gold they extracted, in an area outside of the house, about five times a day.[120] One child explained that it was common for gold traders to have an amalgamation area in their homes: “Most buyers have [an amalgamation area]. They live there. I mix and burn … [the gold and mercury] there.”[121]

Three children told Human Rights Watch that they used mercury at home.[122] Faiza J., a 13-year-old girl, said: “I burn it [the amalgam] on a cooking stove at home…. In the house, not outside … near the dining place.”[123]

Mercury Contamination of Water and Fish

In addition to children being directly exposed through breathing mercury vapor in their homes, they may also be exposed through eating contaminated fish. The use of mercury in mining can contaminate the surrounding environment, including water sources. Bacteria in water can convert mercury into a compound called methylmercury, which collects in fish and puts communities that eat fish at risk of mercury poisoning.

A study by a Tanzanian NGO noted that people build gold processing areas close to wetlands and rivers because water is important for gold extraction.[124] Mining regulations require Primary Mining License holders to construct washing and settling ponds 50 meters away from a water source.[125] However, miners do not always adhere to these standards. Human Rights Watch visited two mines in Chunya district that were located approximately 40 meters away from the Chunya River.

A teacher at one of the schools in the area complained that people were scared to drink the water in Chunya River because of possible contamination from the mines.[126] A representative from the Environmental Sanitation and Hygiene section of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare stated that he had seen a small-scale gold mine in Sinjilili village in Chunya district about 10 meters away from the Sinjilili River.[127] He had also visited a mine in Manyanya village in Chunya district located on the edge of the river.[128]

Moreover, even if washing and settling ponds are more than 50 meters away from water sources, mercury from the mine may still end up in nearby rivers. This can occur if contaminated water overflows from the mine, or through the erosion of contaminated soil or tailings into the river.[129] A 2002 International Labour Organization (ILO) report on child labor in mining stated that in Mlimanjiwa village in Chunya district, “soil erosion is a common phenomenon and rivers are contaminated with mercury.”[130]

Studies have found unsafe levels of mercury in fish adjacent to some gold mining sites in Tanzania. For example, a 2004 United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) study showed that the mercury levels in some fish in the immediate Rwamgasa mining area exceeded international quality guidelines.[131]

Levels of Mercury Exposure in Small-Scale Mining Areas

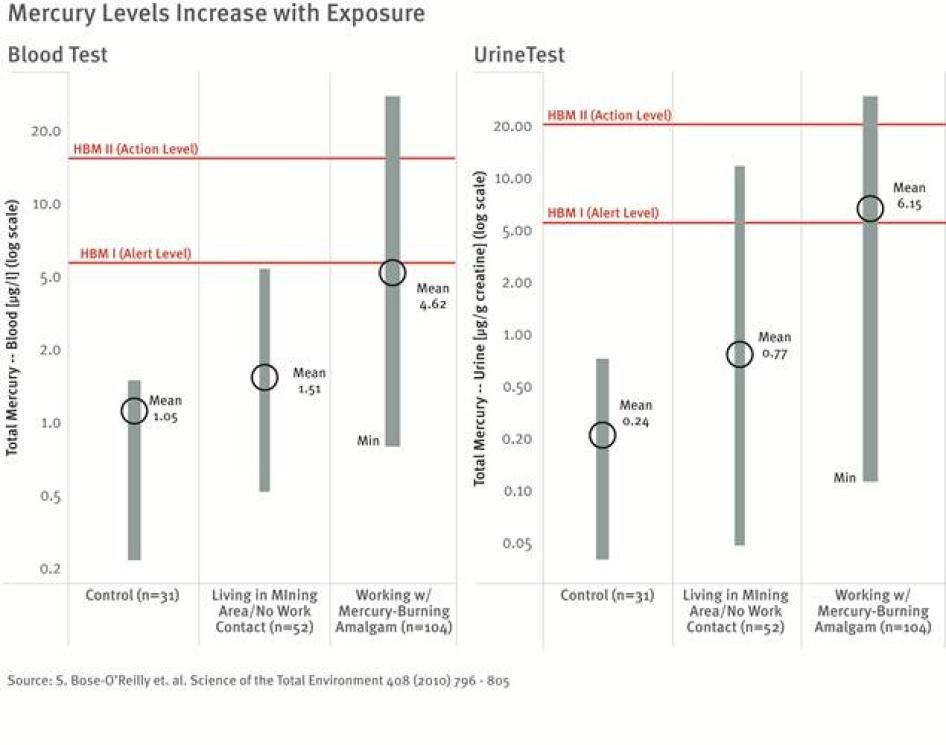

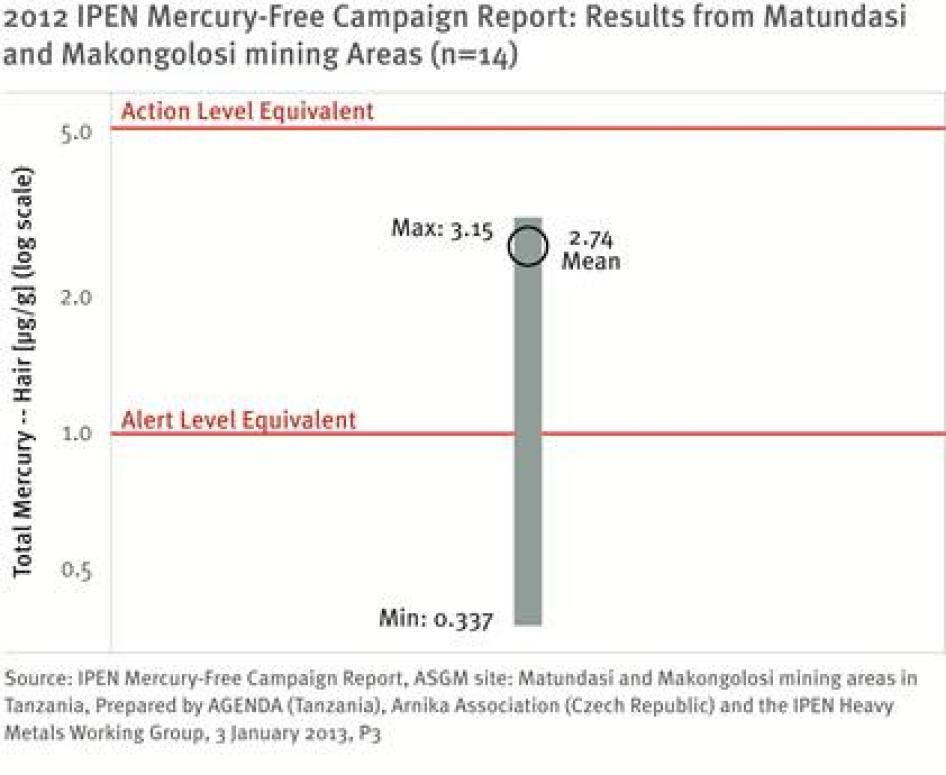

Scientific studies show that people who work or live in Tanzanian mining areas have a higher mercury burden than people living elsewhere in the country. These mercury levels sometimes exceed international safety standards.

For example, as illustrated in the graphs below, a study of adults in Rwamgasa in Geita district showed that the levels of mercury in participants living in Rwamgasa, a small-scale mining area, were higher than the levels of mercury in participants in the control area located 30 kilometers away.[132] Mercury exposure was even higher among miners who burned the mercury-gold amalgam— demonstrating the seriousness of inhaling mercury vapor.

The graphs below also show two threshold values (called Human Biomonitoring levels, HBM) developed by the German Human Biomonitoring Commission to describe the health risk from mercury found in blood and urine.[133] Any results below HBM I are considered “safe” levels of mercury exposure.[134] Results between HBM I and HBM II are “alert” levels where people may suffer from adverse health effects and should take steps to reduce exposure.[135] Mercury levels above HBM II are “action” levels associated with negative health effects where exposure reduction is critical.[136] As seen below, mercury levels in some of the people in the Rwamgasa study who either lived in Rwamgasa or worked in mining, exceeded HBM I and HBM II.

More recent studies continue to show high mercury levels in communities near small-scale gold mines. In a 2012 study, about nine out of fourteen people had mercury levels in their hair that exceeded levels comparable to the HBM I “alert” and HBM II “action levels”.[137] Some of the data for the study was collected in Matundasi in Chunya district, an area visited by Human Rights Watch.

The Health Effects of Mercury Exposure

The inhalation of mercury can lead to a number of harmful health effects. Acute mercury exposure (occurring suddenly) can affect the central nervous system and kidneys and, at higher concentrations, may also impact the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, gastrointestinal tract, and the skin.[138] Chronic mercury exposure (occurring over a long period of time) may affect the central nervous system, gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts, kidneys, oral cavity, lungs, eyes, and skin.[139] Symptoms of mercury intoxication in children include memory and coordination (ataxia) problems and tremors.[140]

Mercury is particularly harmful to fetuses and infants. It can be transmitted in utero and through breast milk.[141] It is highly toxic to the developing brains of infants.[142]

III. Government Efforts to Reduce Child Labor and Mercury Exposure in Gold Mining

Child Labor in Gold Mining

The Tanzanian government has taken some steps to address child labor in mining through the adoption of laws on child labor in hazardous work and through occasional child labor inspections on licensed, small-scale mines. However these initiatives have failed to end child labor in mining, largely because the government is not prioritizing and devoting enough resources to enforce child labor laws in this sector. Officials from the Ministry of Labour and Employment are also failing to conduct child labor inspections on unlicensed mines—the majority of sites—and mining officials rarely check for children during informal visits to these mines. On the few occasions that officials act on child labor, they do not properly assess the age of children and only send younger-looking children away. They also fail to support children’s transition out of child labor through, for example, reporting the children who work in mining to a social welfare officer or re-enrolling them in school.

The government has also failed to adequately address some of the underlying socioeconomic causes of child labor. In particular, the government has not provided adequate support to orphans and other vulnerable children. It also needs to strengthen efforts to eliminate illegal school contributions and to increase the number of children in Tanzania who can continue with their education after primary school.

Child Labor Inspections in Small-Scale Mining: Few and Far Between

Government Officers Failing to Implement and Enforce Child Labor Laws

Despite strong laws and regulations for monitoring child labor, key government institutions are failing to carry out their responsibilities and enforce child labor laws.

Tanzania’s Law of the Child Act, Employment and Labour Relations Act, and the Mining Regulations prohibit children under the age of 18 from engaging in hazardous work, including mining.[143] The government has also adopted a list of hazardous work, under the regulations of the Law of the Child Act, which names and prohibits many forms of labor, including small-scale mining and commercial sexual exploitation.[144]

In June 2009, the Tanzanian government launched a National Action Plan for the Elimination of Child Labor.[145] Under the leadership of the Ministry of Labour and Employment, this ambitious plan aims to reduce the worst forms of child labor in all sectors in the short term, and to eliminate all child labor in the long-term.[146] However, four years later, the government has yet to adequately implement the plan.

A number of government actors are tasked with monitoring and withdrawing children from hazardous labor, but have taken limited action to enforce the laws and policies described above.

At the national level, the Regional Administration and Local Government in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMORALG) chairs the National Intersectoral Coordination Committee on Child Labour, which brings together government ministries, social partners, and civil society organizations to highlight child labor issues and strengthen structures to eliminate child labor.[147] The committee meets twice a year and held its last meeting in December, 2012.[148] The Ministry of Energy and Minerals is not a member of the committee, potentially limiting the flow of information to other groups about children involved in mining.[149]

At the district level, the Ministry of Labour and Employment is the lead ministry for enforcing child labor laws, but it rarely conducts child labor inspections on the mines or enforces penalties on employers who hire children. Seventy-one labor officers are supposed to conduct inspections of all formal businesses across the country.[150] During an inspection, a labor officer may withdraw the child from the activity and serve the employer with a compliance order, which stipulates specific steps and timeframes for remedial action.[151] The officer should also report the matter to a social welfare officer and the police.[152] It is an offense to employ or procure a child for employment in a mine and labor officers may initiate proceedings in the Resident’s or District Court and prosecute the violator in the name of the labour commissioner.[153] Employers who are found guilty may receive a fine, imprisonment, or both.[154]

Although the Ministry of Labour and Employment appears to have had some success in addressing child labor, labor officers rarely conduct inspections for child labor in small-scale gold mining. During the 2011-2012 reporting period, the Ministry of Labour and Employment only conducted 2,401 inspections in all workplaces, which is 38.7 percent of its target of 6,200 inspections.[155] The Ministry stated that it withdrew 17,243 children and prevented 5,073 children from engaging in the worst forms of child labor during this period.[156] Tanzania has 12 main mining regions, but children were only withdrawn or prevented from entering into the worst forms of child labor in five of these areas.[157] Roughly 91 percent of the children withdrawn from the worst forms of child labor came from Tabora, a gold mining region, but most of them worked in agriculture.[158]

The labor offices visited by Human Rights Watch lacked sufficient staff and resources to conduct inspections in mining areas. The Mbeya regional office has only two officers and operates on a limited budget.[159] It only conducts approximately 20 to 25 inspections annually in all sectors, not just mining.[160] In the last two years, Mbeya labor officers only conducted two inspections of artisanal mines in Chunya—these were prompted by complaints of workers about pay, not about child labor.[161] A labor office in Mwanza, with three labor officers, similarly suffered from resource constraints and lacked fuel for transportation to the mining areas in Geita district.[162] A labor officer from Mwanza recalled only visiting small-scale gold mines in Geita district once, as part of a donor-supported child labor project in March 2012.[163]

Labor officers are also failing to take strong action against employers who violate child labor laws. One regional office stated that it had not yet issued a compliance order for child labor.[164] During the 2011-2012 period, only two compliance orders were issued in mining—one in Mwanza and the other in Shinyanga.[165] There have also been very few, if any, recent prosecutions for child labor.[166] According to labor officers, they primarily educate people who employ children about the labor laws and advise them to take remedial action.[167]

Another important entity tasked with monitoring child labor in mining is the Ministry of Energy and Minerals. Mining officials may request a Primary Mining License holder that has hired children to take remedial action or pay a fine.[168]

However, mining offices lack sufficient staff to carry out regular inspections of small-scale mines.[169] One mining official described the shortage of workers as one of the biggest challenges faced by the ministry.[170] Because the Ministry of Energy and Minerals does not have a presence in every district, it has limited monitoring capacity and must sometimes rely on the district commissioner and district executive director, who lead and manage the local government.[171] In particular, the district commissioner and the district executive director play a substantial role in helping to remove miners from large, illegal, gold rush sites.

When the inspectors from the Ministry of Energy and Minerals do visit licensed mines, they tend to prioritize revenue collection and other health and safety issues over the problem of child labor. They visit large and small-scale mines to check for compliance with safety, environmental and other regulations, as well as collect royalties on a regular basis. One mining officer explained:

If someone is given a work to inspect and make sure that there is … compliance … that means he must be a law enforcer. At the same time you are given the task to collect revenue. And the prime objective of the government at the end of the day… [is] whether you have attained the target of the collection…. [The government will] judge you according to what you have collected.[172]

In one case, a representative of the Ministry of Energy and Minerals believed that village authorities were responsible for acting on child labor, not mining officials.[173]The government has acknowledged that lack of understanding of child labor laws is a common problem among many government departments.[174]

When mining officials act on child labor, they rarely impose fines on employers. Like labor officers, mine inspectors usually raise awareness about child labor laws with employers or in some cases, issue warnings if they find children on a mining site.[175]

Government actors from the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, and the Ministry of Community Development, Gender and Children, oversee community development officers and social welfare officers who should raise awareness of child labor issues in mining villages, monitor child labor at the district and village level, and report their findings to the prime minister’s office.[176]However, community development officers in two of the district offices visited by Human Rights Watch were severely short-staffed and often lacked adequate resources to carry out their work.[177]

Finally, at the village level, village authorities have no responsibility to enforce child labor laws, but can adopt legally enforceable bylaws to help to discourage child labor. None of the villages visited by Human Rights Watch had such bylaws in place. Also, according to village authorities in Kahama district, it is difficult to impose village laws on migrant populations in the area.[178]

Unchecked Unlicensed Mines

Mining and labor officials also seldom conduct child labor inspections on unlicensed gold mines. Twenty-eight of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch worked on unlicensed gold rush sites, suggesting they are significant sources of child labor.

Labor officers are authorized to enter any “premises” for inspection—which could theoretically include businesses in the informal sector.[179] However, labor officers infrequently inspect informal businesses.[180]

Mining officials sometimes visit unlicensed sites to address legal, security, and safety concerns, and to collect taxes– but generally not to look for children.[181] A mining official in Chunya district explained, “Sometimes we do go there [to unlicensed mines] and find out … where they are actually working illegally, to inform the owner … If we find that the situation is somehow serious and might cause a risk and death to them, we might tell them to stop.”[182] Mining officials are sometimes wary of visiting unlicensed mines because they do not want to appear to provide the site official recognition and legitimacy.[183]

The Tanzanian government recognizes the need to formalize and professionalize the artisanal mining sector and has embarked on a formalization program. This includes efforts to free up land for unlicensed miners, because there are currently few areas remaining where miners can apply for a mining license.[184] But formalization is a long process. In the interim, the Ministry of Labour and Employment should exercise some oversight over unlicensed mines and, during informal visits, officials from the Ministry of Energy and Minerals should check unlicensed sites for children engaged in unlawful child labor.

Flawed Government Inspections

On the few occasions that government officials conduct child labor inspections, they often fail to stop child labor. Human Rights Watch found evidence of at least one government intervention in Kahama district that prompted children to leave the mine and return to school, but others overlooked older adolescents and did not stop children from returning to the mine.

Human Rights Watch visited a gold rush site in Kahama district where, even though they were not required to act under the law, ward and village authorities enforced child labor laws.[185] Enos F., a 13-year-old child working in mining, explained that towards the end of the school holidays, the village government told children to vacate the mines so they could attend classes.[186] Several children returned to school. This intervention may have been successful because village authorities were present to enforce the ban on children in mining.

However, in a number of other cases in Chunya district, government officials failed to identify older children working on the mines and take adequate action to prevent children from returning to the mines. Human Rights Watch interviewed inspectors who said they determined the age of a child by looking at the child’s appearance. An official from the Ministry of Energy and Minerals said that inspectors “just look” at the child to determine his or her age, and a labor officer said he interviewed children to determine their ages.[187] Many children’s births are not registered so officials should conduct rigorous interviews with various people on the mine to determine children’s ages. If they do not, children like Rashid A., a 17-year old boy, will work on the mines unnoticed. He explained, “They [officials] are not bothered with me, they think I am big.”[188]

Two child laborers told Human Rights Watch that they returned to the mines after a government official inspecting the mines sent them away.[189] In one case, a child identified the official as an inspector from the Ministry of Energy and Minerals.[190] None mentioned receiving assistance to transition out of child labor into school or vocational training. Thirteen-year-old Rahim T. explained, “They chased us and said ‘don’t come again.’ I went again. I work at that particular mine and other places…. If we are chased we go to search for other areas.”[191]

Inadequate Support for Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children

Orphans are particularly likely to be involved in the worst forms of child labor, because of inadequate support from guardians or extended family members, and other factors which contribute to their vulnerability such as gender, health status, and remarriage of the surviving parent or caregiver.[192] Like many children, some orphans seek employment in mining to cover their needs. The government should provide greater economic and psychosocial support to orphans and other vulnerable children to curb child labor.

Few orphans and other vulnerable children receive direct assistance from the government. Unable to survive, some seek employment in mining. Each village is supposed to have a committee to identify vulnerable children.[193] Local government is responsible for addressing community needs but because of the gap in resources, officials often look to local NGOs for assistance.[194] However, even with outside help, demand for support remains high. A 2008 government study found that only 7 percent of orphans and vulnerable children received at least one type of external support, most of which came in the form of school-related assistance.[195] Some of the orphans interviewed by Human Rights Watch used their money to purchase basic necessities such as food, clothing, shelter, and provisions for going to school, such as uniforms and other fees.[196] Joana S., a 15-year-old girl whose parents died when she was very young, said she lived with her older sister and received some support from a local NGO, but still complained of experiencing hunger. She explained that the reason she first went to the mine was “due to the situation at home I had no option. The conditions I was living in … my sister told me to go.”[197]

The government should support orphans and vulnerable children, and address child labor, by committing adequate resources to social protection strategies, such as income or in-kind support for very poor households, and programs to increase access to services such as healthcare, nutrition and education.[198] In a promising step, the government recently adopted its National Costed Plan of Action for Most Vulnerable Children for 2013 to 2017, led by the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, in conjunction with other ministries, development partners and stakeholders.[199] This plan is targeted at children living with severe deprivations such as orphans and children engaged in the worst forms of child labor. Some of its key objectives include strengthening the capacity of households and communities to protect, care, and support the most vulnerable children, providing a regulatory framework for a child protection system, expanding access to health and education, and strengthening coordination, leadership, policy and service delivery.[200] However, at the time of writing, the government had yet to provide funding to implement the plan.

Although limited in scope, another promising initiative is the third Tanzania Social Action Fund (TASAF III) which provides grants and conditional cash transfers to vulnerable populations. President Kikwete launched TASAF III, supported by the World Bank, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in August 2012. TASAF III was designed to provide a community-based cash transfer to certain families living under the poverty line who are able to comply with conditions such as “school attendance for children, regular health check-ups for under-five children and the elderly, incentives for girls to remain in school, incentives for pregnant women to deliver at health facilities, ensuring nutrition for children through information on meal preparation, and micro-nutrient initiative supplements.”[201] The program targets 275,000 households—a small fraction of the Tanzanians who live below the poverty line.[202] During the current phase of TASAF III, the government will provide infrastructure such as schools to support the project.[203] Other aid agencies should commit resources to scale up the program and ensure greater support for orphans and other vulnerable children.

Weaknesses in Education Policies

Weaknesses in the education system contribute to child labor in Tanzania. In particular, the government has failed to abolish unlawful financial contributions at the primary school level and ensure access to post-primary educational opportunities.

Failure to Eliminate Primary School Contributions and Expenses

Even though the National Education Act and the 2002-2006 Education Development Plan have secured children’s rights to a free and compulsory primary education, in practice children must pay a range of illegal contributions and other expenses.[204] With roughly 67.9 percent of the population living below the international poverty line of US$1.25 per day, many parents may struggle with even small school-related expenses.[205] These costs can cause children to seek additional income from the mines and can contribute to their dropping out of school.