Summary

I don't like the idea that the international community only waits for bloodshed and open war to come with aid.

– A clergyman in Kumbo, North-West region, April 2018

Cameroon, a bilingual and multicultural country known for its stability and its strong alliances with France and the US, is slipping into a protracted human rights crisis in the largely Anglophone North-West and South-West regions that border Nigeria.

Since late 2016, Anglophone activists, who have long complained of their regions’ perceived marginalization by the Francophone majority, have mobilized significant segments of the Anglophone population to demand more political autonomy or secession.

Between October and December 2016, English-speaking lawyers, teachers, and students took to the streets to protest the perceived “francization” of the regions’ educational and judicial systems by the central government. In response, government security forces heavily clamped down on protests, arrested hundreds of demonstrators, including children, killed at least four, and wounded many.

In early 2017, the government negotiated with the lawyers and teachers’ unions. The government claimed to have agreed to their demands, including the creation of a National Commission for Bilingualism and Multiculturalism and the recruitment of bilingual magistrates and teachers by the government, but this did little to deescalate the crisis. The government’s repression and arrest of prominent Anglophone negotiators on January 17, 2017, emboldened more extremist leaders who began to demand, increasingly violently, independence for Cameroon’s Anglophone North-West and South-West regions – a territory they call “Ambazonia.”

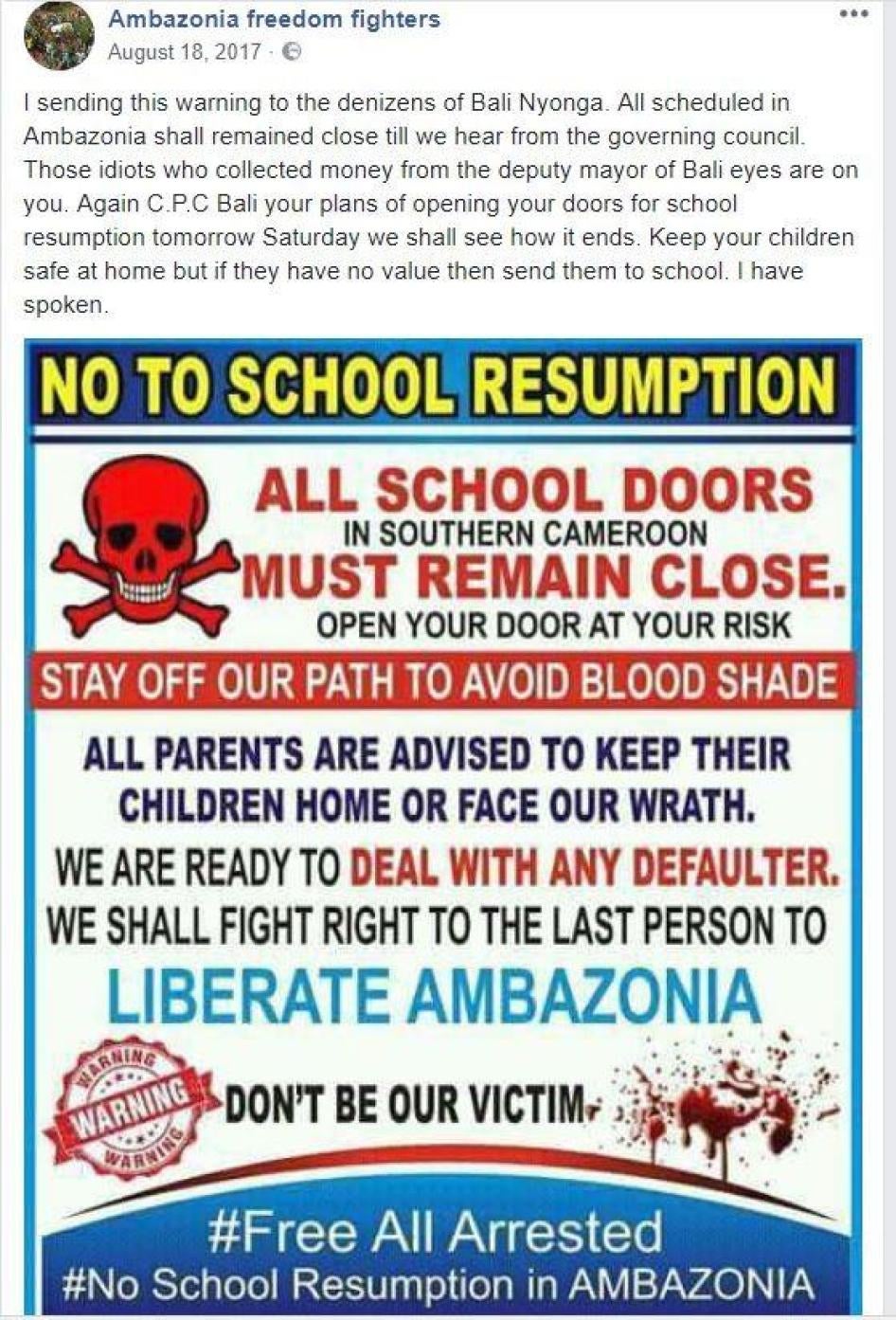

In 2017, separatist activists began to burn school buildings, threatening education officials with violence if they did not enforce a boycott of schools in the Anglophone regions. As of June 2018, UNICEF indicated that 58 schools had been damaged in the two regions. The separatists’ attacks on education, analyzed by many in the North-West and South-West as an attempt to render the regions ungovernable, have created an environment that has been preventing tens of thousands of children from attending classes over the past two school years. Around the same time, Anglophone diaspora groups in the US, Europe, and Nigeria agreed to form an interim government for the “Republic of Ambazonia” and called for mass demonstrations on September 22 and October 1, 2017 to celebrate their regions’ self-proclaimed independence.

Government security forces again responded abusively to the demonstrations in the larger cities of Buea, Kumba, and Bamenda, including with use of live ammunition against protesters, killing over 20 people, wounding scores of civilians, and arresting hundreds, according to witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch and credible reports by media and human rights organizations. There are indications that the repression contributed to the radicalization of the pro-independence discourse, and its supporters carried out more attacks on schools and, increasingly, on government outposts in the backcountry.

In early January 2018, Nigerian authorities arrested 47 Cameroonian Anglophone activists in Nigeria, including the “interim president” of the “Republic of Ambazonia” and members of his cabinet. Nigeria then handed them over to Cameroonian authorities. According to credible reports, which the Cameroonian government confirmed, the 47 were held incommunicado for six months. In June, the Cameroonian government allowed some of them to meet their lawyers and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) met them all for the first time.

Following the arrests in Nigeria, armed separatists mobilized more members and resources and began to ambush security forces or shoot at their bases in a more regular and organized fashion. In response, government security forces carried out abusive counterinsurgency operations that over a dozen of villagers consistently described in individual interviews as including wholesale attacks on villages, the burning and destruction of property, and the killing of civilians, including older persons and people with disabilities who were left behind when others fled.

Scores of civilians are believed to have been killed by both sides since 2016 when the crisis began. In a June report on the humanitarian crisis in the North-West and South-West, the government claimed that over 80 security force personnel have been killed by suspected armed separatists. Human rights organizations and the media reported that security forces have killed dozens of civilians in heavy-handed government security operations responding to the protests and growing insurgency.

This report, based on interviews with over 80 witnesses and victims of abuses during a Human Rights Watch research mission to the Anglophone regions of Cameroon in April 2018, documents abuses committed by both armed separatists and government forces since late 2016. These include extrajudicial executions, excessive use of force and the unjustifiable use of firearms against mostly unarmed demonstrators, torture and ill-treatment of suspected separatists and other detainees, and the burning of homes and property in several villages by government security forces. Abuses perpetrated by the separatists included threats against teachers and parents aimed at preventing them from sending their children to class, attacks on schools, killings, kidnappings, and extortion of civilians and state workers.

In June, Human Rights Watch representatives met with senior government ministers, including the top adviser to the president and the ministers of defence, the interior, foreign affairs, justice and communications to present the findings and sought the government’s perspective on the crisis.

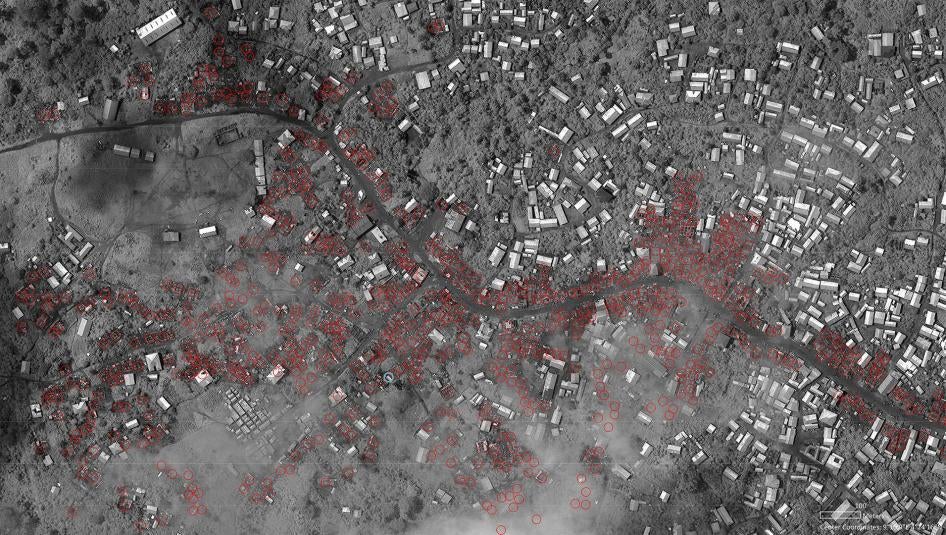

Through satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch assessed a total of 131 villages and was able to identify several hundred homes showing signs of destruction consistent with arson in 20 villages of the South-West region alone. Testimonies indicated that security forces were responsible for the burnings. Human Rights Watch interviewed villagers from five of the villages analyzed – Kwakwa, Kombone, Bole, Wone, and Mongo Ndor – who described fleeing as security forces entered the village, then watching smoke rise into the air. Attacks on seven more villages were documented in which burning either did not take place or could not be confirmed by satellite because of cloud coverage.

According to these same witnesses, four elderly women left behind during government operations in Kwakwa, Bole, and Mongo Ndor and were reported burnt alive in their homes. Security forces allegedly shot dead several others in Kwakwa, Wone, Bole, and Belo, including seven people with intellectual or developmental disabilities who had difficulty fleeing.

“They came to the house that I took 10 years to build. They came and burned our compound. Everything was burned,” a victim in North-West region told Human Rights Watch. “Now, I live in misery. I am lost. I have no job, no money, no house, no food, no clothing. I used to stand strong, but this one… I feel psychologically defeated. I don’t know where to start.”

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said that since December 2017, the violence has resulted in the internal displacement of over 160,000 people in the North-West and South-West regions, with many of them hiding in the forests. Between 20,000 and 50,000 more, according to UN Refugees Agency (UNHCR), fled across the border to Nigeria's Benue and Cross River states. But government figures put the number of internally displaced persons in the two regions at 75,000.

Faced with the prospect of intensification of the violence and human rights abuses, Cameroon should urgently convene a mediated dialogue with Anglophone civil society, diaspora groups, and armed separatists. International actors should back and support these efforts.

The government should immediately ensure that its security forces end their abusive counter-insurgency tactics, which have clearly aggravated the situation, impartially investigate allegations of abuses against civilians by its forces, and publicly hold those responsible to account.

The government should allow independent observers and aid organizations to access the region to monitor the situation and provide aid to the tens of thousands of internally displaced civilians. Government authorities and aid organizations should also respond to the education crisis by transporting students to schools in regions that are not affected by the crisis. In addition, the government should campaign for the tens of thousands of children who have been out of school for the past two years to return to school and promote alternative forms of education including teaching by radio, the internet, or television.

Leaders of armed separatist groups should ensure that their followers stop all abuses against civilians in the regions where they operate. Separatists should immediately end violent threats and attacks on schools and allow for the full and safe resumption of classes throughout the region.

As the situation continues to deteriorate, international actors including the African Union and the United Nations should closely monitor the evolution of the parties’ behavior and press the government and armed separatists to accept a third-party mediation led by an independent and trustworthy international actor.

Governments of countries hosting Anglophone diaspora populations, such as Canada, the US, United Kingdom, Belgium, Nigeria and South Africa, should also investigate the role of some individuals in inciting violence.

Recommendations

To the Government of the Republic of Cameroon

- Ensure that any security operations are conducted with full respect for international human rights law, notably by abiding with the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Firearms, respecting the principles of proportionality, and deploying military judicial police officers on operations to monitor the conduct of security forces and advise commanding officers;

- Ensure that all victims of human rights violations have access to effective remedies, including easy access to complaint mechanisms against security forces, a witness protection regime if necessary, and the possibility to participate in a transparent judicial process against perpetrators;

- Investigate all allegations of violations by security forces and hold those responsible to account;

- Consider seeking the support of an independent and trustworthy international third-party such as the UN or the Catholic Church to engage in a comprehensive mediation process with all relevant Anglophone actors in order to try and address the root causes of the current human rights crisis;

- Respect freedom of assembly and expression, including by ensuring that internet access remains unhampered and committing to keep it open;

- Promptly charge or release all those detained in the context of the Anglophone crisis, including the 47 Anglophone activists arrested in Nigeria, and ensure that any future detainees are brought before a judge within 48 hours of their arrest, in line with the Cameroon’s Penal Procedure Code;

- Ensure that those charged with offences enjoy full due process, and that any and all charges are supported by credible evidence;

- Ensure that civilians charged with criminal offences are tried in civilian courts;

- Ensure that all detainees enjoy humane and dignified treatment, including appropriate accommodation space, food and water, and are at no time subjected to any form of torture or cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment while in custody;

- Allow and facilitate unfettered humanitarian access to the North-West and South-West regions;

- Accept visits by relevant UN Special Procedures and facilitate monitoring and reporting by independent observers and rights groups;

- Respond to the education crisis by providing alternative forms of education and preparing remedial catch-up programs and a campaign with necessary incentives to get children who have been out of school for two years to return to school;

- Promptly endorse and implement the Safe Schools Declaration.

To Armed Separatist Groups

- Publicly announce an end to the school boycott and immediately cease attacks on schools, teachers and education officials, and allow for the safe return of all students to class;

- Disseminate policies among all members prohibiting threats on students or teachers, attacks on schools, or the use of schools for military purposes;

- Ensure that all groups refrain from committing human rights abuses, including killings of civilians, torture, kidnapping, and extortion;

- Immediately release all civilians illegally detained or kidnapped.

To the African Union

- Call on Cameroon’s government and all armed separatists to end all attacks on civilians and facilitate immediate resumption of school;

- The African Commission for People and Human Rights’ Special Rapporteurs on the Rights of Refugees, Asylum Seekers, Migrants and Internally Displaced Persons should request an invitation to visit Cameroon and publicly report on the situation.

To the United Nations

- The UN Security Council should request a briefing by the UN Secretary General on the situation in Cameroon, demand an end to human rights violations, and make clear that further abuse may lead to targeted sanctions, including against individuals credibly implicated in serious violations;

- Implement the “Human Rights Up Front” agenda including at the country team level by prioritizing human rights protection in the Anglophone crisis response and by sharing information through regional monthly reviews;

- The UN Secretary General should raise the situation in Cameroon with the UN Security Council as a situation that could threaten international peace and security. The Human Rights Council should mandate an investigation into violations and abuses, through a mission dispatched by the High Commissioner for Human Rights or joint report by relevant Special Procedures, and encourage Cameroon to cooperate with such an investigation and facilitate access to the affected areas;

- The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and relevant Special Procedures should monitor the situation, and keep the Human Rights Council regularly informed;

- Conduct proper screening of all Cameroonian security forces meant to join UN peacekeeping operations and exclude all individuals or units suspected of human rights violations in line with the UN Human Rights Due Diligence Policy.

To Cameroon’s International Partners, including France, the US, and United Kingdom

- Review any support to Cameroonian security forces and ensure that it does not contribute to or facilitate the perpetration of human rights violations;

- Strongly condemn human rights violations by all actors and separatists threats and attacks of teachers and schools as impermissible and unacceptable in any conflict or political struggle.

Methodology

This report is based on 82 interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch during a three-week mission to the North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon in April 2018.

Human Rights Watch carried out research in Bamenda and Kumbo in the North-West region, and Kumba in the South-West region. For security reasons, researchers were unable to access some of the affected divisions of the two regions but they interviewed internally displaced people who came from such areas.

Interviewees were identified with the help of an extensive network of contacts in both regions. Interviews were conducted individually and in private except for five interviews in which family members or close friends were present. Most interviews were conducted in English or French. Three interviews were conducted in Pidgin English with the help of a trusted translator.

We informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which data would be collected and used. The names and other identifying information of all our interlocutors have been withheld, and in some cases replaced with pseudonyms.

Researchers also collected documentary evidence, including written complaints to a local organization following acts of repression by security forces and dozens of videos and photographs showing casualties and destructions allegedly caused by security forces or security forces abusing civilians or burning villages. A number of those videos were forensically analyzed, compared to satellite imagery, and verified by Human Rights Watch specialists.

Human Rights Watch also obtained and analyzed satellite images covering much of the territory where interviewees alleged government security forces burned villages.

In June, a Human Rights Watch delegation visited Cameroon and met with the Secretary General of the Presidency, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Secretary of State for Defense, the Minister of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, the Minister of Justice, the Minister of Communications, the Minister of Basic Education, and the Minister of Secondary Education.

We presented these senior Cameroonian officials with our research findings and sought their perspective on the situation, urging them to abide by Cameroon’s international obligations.

I. Context

The Anglophone regions of Cameroon are located in the North-West and South-West administrative regions and comprise a fifth of the country’s population of about 25 million.[1] The North-West region’s capital – Bamenda – is the country’s third largest city while the South-West region sits on the eastern shores of the Niger delta, where an important part of Cameroon’s oil reserves is found.[2] Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis is rooted in the country’s colonial history and tensions surrounding its independence first as a federation and then a unitary state.

Cameroon’s Path to Independence and Authoritarian Rule

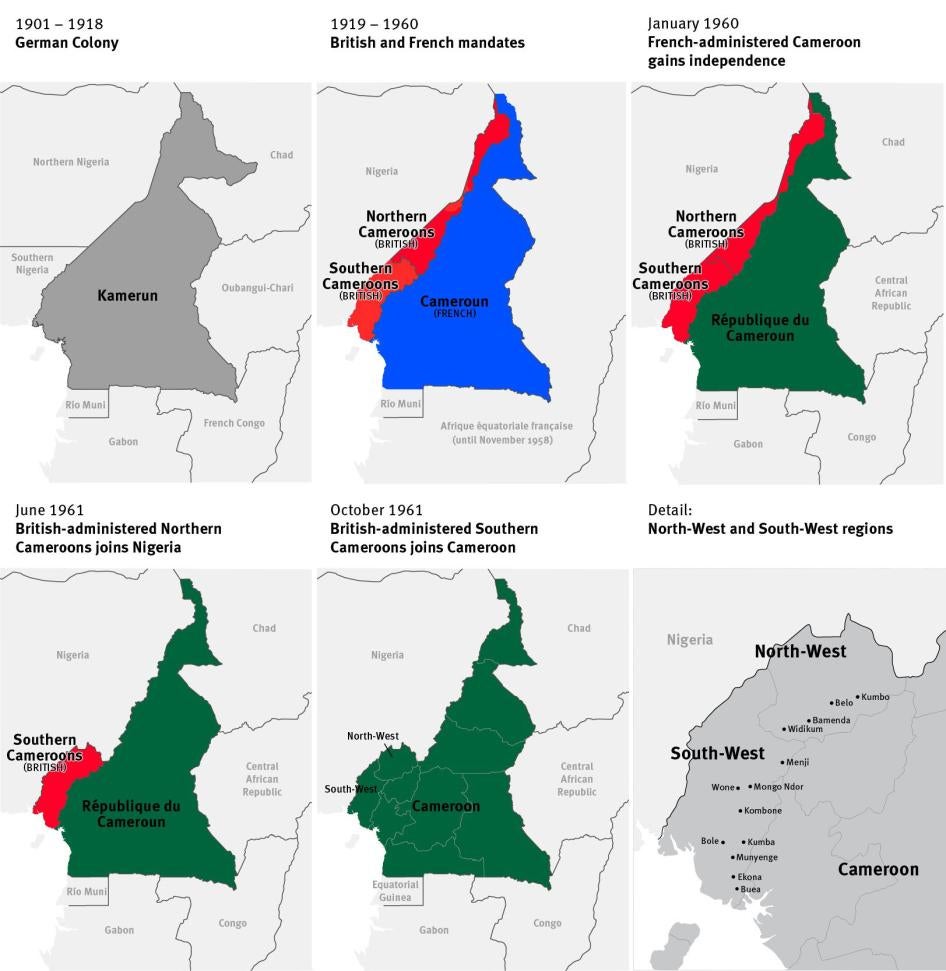

Initially a German colony, Kamerun, as it was then known, was divided by the League of Nations under French and British mandates shortly after the end of World War I. The British were granted a small band of territory bordering what is now Nigeria while the French got a larger share in the center and east of the territory.[3] These became United Nations trust territories under French and British trustees in December in 1946.[4]

During the four decades of British and French administrations, the two areas were subjected to vastly different legal, political, and administrative systems, as well as socio-cultural mores.[5]

In 1961, UN-sponsored plebiscites were held to determine whether the Northern and Southern Cameroons under United Kingdom administration would join the new Federation of Nigeria or the newly independent francophone République du Cameroun.[6] The Northern Cameroons chose to join Nigeria, while the Southern Cameroons chose to federate with the République du Cameroun thus creating an officially bilingual Federal Republic in which the Francophone and Anglophone education and legal systems were meant to coexist.[7]

The new federation, presided by Ahmadou Ahidjo and an Anglophone vice-president, quickly became a single-party state in which the president consolidated power through repression.[8] By referendum vote in 1972, Cameroonians adopted a unitary government – thereby abolishing the federation – and renamed the country the United Republic of Cameroon.[9] In this system, dominated by a centralized, francophone government, the Anglophone minority began to complain of marginalization.

Ten years later, Ahidjo resigned stating health reasons, paving the way for the swearing-in as president of his long-time prime minister Paul Biya.[10]

In the early 1990s, President Biya enacted constitutional reforms in response to opposition calls for multiparty democracy.[11] Biya was reelected in 1992, 1997, 2004, and 2011, following elections marred by allegations of fraud and continued repression of political opposition. Biya, 85, is up for reelection in October 2018.[12]

In February 2008, a wave of violent riots caused by a rise in oil prices and Biya’s declared intention to modify the constitution to allow him to run in the 2011 presidential elections swept across several towns throughout Cameroon.[13] While the president called for calm, security forces arrested over 1,600 protesters and used force to repress the riots. At least 40 people reportedly died.[14]

Less than two months later, the ruling party-controlled legislative assembly voted to remove terms limits, and in 2011 Biya was reelected for a sixth term with 77.99 percent of the vote.[15]

The “Anglophone Problem” and the Rise of Separatism

In 1993, an “All-Anglophone Conference” convened in Buea, the former capital of the British-administered Cameroons, and called for a return to federalism.[16] The government rejected the federalists’ calls but pledged to adopt some reforms to decentralize power.[17]

The following year, a second “All-Anglophone Conference” issued the Bamenda declaration, again recommending a two-state federal system or alternatively, secession. The government did not change its course and maintained its position of support for the unitary system.[18]

In the wake of the Bamenda declaration, Anglophone groups began to publicly call for the former Southern Cameroons’ secession. The most prominent of these groups, the Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC), began to campaign diplomatically at the United Nations, the Commonwealth, the African Court of Human Rights and the African Union for the region to be recognized as independent.[19]

The Late 2016 Protests

Cameroon’s legal and educational systems became flashpoints for Anglophone activists. In late 2016, Anglophone lawyers and teachers went on strike in the South-West and North-West regions to protest the deployment of francophone magistrates and teachers to the area.

In early January 2017, as activists called for more demonstrations in the North-West and South-West regions, members of the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CACSC), agreed to meet with the government to urge the release of protesters arrested during a violently-repressed demonstration in Bamenda on December 8, 2016.[20] Yet, as the talks were ongoing, the Consortium accused the government of shooting four unarmed youth and declared “ghost towns” – in which businesses are encouraged to remain closed – on January 16 and 17.[21]

In response, the government cut the internet and banned the activities of two groups, the Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) and the Consortium, on January 17, 2017.[22] The same day, two prominent Anglophone civil society activists who headed the Consortium – Felix Agbor Nkongho and Dr Fontem Neba – were arrested and transferred to Yaoundé.[23] Two days later, Mancho Bibixy, a separatist leader was also arrested, alongside six other activists.[24]

In the aftermath of the arrests, some Consortium and SCNC leaders fled to Nigeria, where they formed the Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front (SCACUF). Among the SCACUF were groups and individuals that advocated and prepared for armed struggle against the Cameroon government.

On July 8, 2017, the SCACUF chose Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe, a British-educated engineer and Chief Information Officer of the American University of Nigeria, as its leader and the interim president of the “Republic of Ambazonia,” the entity they claim has sovereignty over the former British-administered Southern Cameroons.[25]

The Late 2017 Protests

While the ghost town protests continued throughout 2017, violence did not escalate substantially until the middle of the year, when two schools that had advertised their reopening ahead of the new school year were burned, allegedly by pro-independence activists.[26]

In a bid to reduce tensions in September, the government released Felix Agbor Nkongho and Dr. Fontem Neba by presidential amnesty.[27] However, a dozen more Anglophone activists remained detained, including Mancho Bibixy, and militant pro-independence factions continued to mobilize the population.[28]

On September 22, 2017, as President Biya prepared to deliver his speech at the UN General Assembly, tens of thousands of demonstrators mobilized by the SCACUF poured into the streets of the North-West and South-West regions to show their support in favor of independence.

On October 1, SCACUF and other pro-independence organizations called for mass demonstrations via social media and press declarations to celebrate the proclamation of the “Republic of Ambazonia.”[29]

Witnesses and victims told Human Rights Watch in Bamenda, Kumbo, and Kumba that security forces used live ammunitions against largely peaceful protesters and at times shot at demonstrators from helicopters. Security forces arrested at least 500 civilians and killed over 20 between September 22 and October 2, according to Amnesty International.[30]

In late October, separatist leaders announced the formation of an Interim Government of Ambazonia, headed by Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe as president.[31] Shortly thereafter, the Cameroon government issued 15 international arrest warrants for separatist leaders, including Ayuk Tabe.[32] President Biya’s rhetoric also hardened; on November 30, he announced that Cameroon was under attack from terrorists and vowed to “eradicate these criminals” to bring back peace and security.[33]

The Arrest and Deportation of the 47

The crisis further escalated when Nigerian authorities arrested Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe and at least six of his putative cabinet members during a meeting at the Nera Hotel in Abuja on January 5, 2018. On January 22, those men and three dozen other Anglophone activists – a total of 47 – were handed over to the Cameroonian authorities.[34]

On January 29, the Cameroon government acknowledged having custody of the 47 and stated that they would answer for their crimes.[35] According to credible reports, which the Cameroonian government confirmed, the 47 were held incommunicado for six months. In June, the Cameroonian government allowed some of them to meet their lawyers and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) met them all for the first time.[36]

II. Abuses by Armed Separatist Groups

Groups of armed separatists emerged following the government’s suppression of the 2016 demonstrations, and gained further support from the diaspora and local communities after the government’s heavy-handed response to the September and October 2017 demonstrations.

Many of these groups have a robust following online and appear to be supported by strong diaspora networks in the US, United Kingdom, Nigeria, and South Africa. Some of these foreign-based online activists have since proclaimed themselves to be “commanders” of armed groups and many have used inflammatory and hateful rhetoric against Francophones and government security forces, calling them “dogs,” “animals,” or “terrorists,” accusing them of “genocide,” and urging fighters to send them “home to meet their father Lucifer.”[37]

According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Database (ACLED), an independent media monitor, the pace and scale of attacks by armed separatists against security forces, government workers, and state institutions more than doubled in late 2017 and continued to increase following the January 2018 arrest and deportation of the 47 secessionist activists from Nigeria.[38]

|

How many groups are there?

An independent Cameroonian journalist who has investigated the groups and spoke to Human Rights Watch estimates that between 5 and 20 groups operate in the two regions.[39] In a December 2017 statement, the International Crisis Group (ICG) estimated the various groups comprise about 500 fighters in total.[40] The most militant and well-known groups include: · The Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF), which emerged in late 2017 under the reported command of Ayaba Cho Lucas, a former Southern Cameroons Youth League activist, now self-styled leader-in-exile and commander-in-chief of the Ambazonia Governing Council, operating mostly in the South-West’s Mamfe area; · The Southern Cameroons Defense Forces (SOCADEF), reportedly with a presence in the South-West region’s administrative division of Meme and under the control of Ebenezer Akwanga, a former political prisoner now living in the US, and an individual known as “General Molua C”; · The Lebialem Red Dragons, with a reported presence in the South-West’s Lebialem division and; · The Ambazonia Self-Defence Council, created by the putative “Interim Government” in March 2018 and encompassing: o The Ambazonia Restoration Army, a militia reportedly under control of General Paxson Agbor, a former police officer; o The Tigers of Ambazonia, a militia with a presence in the South-West region’s Meme and Manyu divisions; o The Southern Cameroons Defense Forces (SCDF), led by Nso Foncha Nkem, an Anglophone Cameroonian who is rumored to have served in the US army, and; o The Manyu Ghost Warriors, with a presence in the South-West region’s Manyu division.[41] It is unclear how these groups are structured and to what degree they coordinate with one another. An independent journalist, a local civil society activist, and three villagers from two different localities told researchers that some groups have a structure at the local level, with village level commanders appearing to report to regional commanders.[42] “It is structured as such that they have a general or a leader for each village,” a civil society activist who traveled to areas controlled by armed separatists in March 2018 told Human Rights Watch. “We were stopped at a checkpoint by Ambazonian boys. When I said that I am with an NGO, they pulled me aside. I was questioned and eventually the leader let me go after getting instructions on the phone from someone else,” she said.[43] |

The government said that armed separatists have killed over 100 civilians and 84 security forces personnel since the conflict erupted.[44] While Human Rights Watch has not been able to ascertain the total number of civilian fatalities by armed separatists, witness accounts and credible media reports present strong evidence that civilians perceived to collaborate with the government have also been targeted by these groups for extortion, torture, and murder.[45]

In the South-West region’s Meme division for instance, armed separatists have targeted at least two civilians who hail from the mostly francophone Bamileke ethnic group for kidnapping and extortion. Two Bamileke traders told Human Rights Watch that in February 2018 a group of armed separatists came to one’s home and the other’s shop and accused them of supporting the government, badly beating one of them. One of the traders recalled:

These youths took me to their chief and he asked if I was Bamileke. I said yes and then he said that they would kill us all. They beat me with their guns and the flat side of a machete. I was on the ground and bleeding. They wanted me to confess that I was a traitor. I refused so they let me go after I gave them money.[46]

In another case, a local civil society activist recounted how she heard from villagers that the armed separatists located in Foe Bakundu executed a man they accused of being an informant in March 2018. “They tortured him and he died,” she said.[47]

Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools

In November 2016, Anglophone teachers went on strike to protest perceived discrimination against English-speaking teachers and students in the country’s education system.

A private school principal told Human Rights Watch he thought the November 2016 strike would only last a few days. “We had a class with [the students] and told them on Monday the 21st, ‘Don’t come to school because teachers trade union is calling a strike.’ We thought that the strike would last one to two days as normal,” he said. “Little did we know that it would last until the situation we have today.”[48]

The majority of teacher unions called off their strike in February 2017.[49] “We had made our point and we wanted to go back to school,” one union leader involved in the deliberations told Human Rights Watch.[50] But separatist activists continued to push the local population to refrain from returning their children to school as a tactic to pressure the government.

A teacher told Human Rights Watch: “The general information was that everyone should boycott [schools]. So there were those who were respecting it out of convictions and others respecting it out of fear that something would happen to their children.”[51]

Kidnapping of Principals

In 2018, armed separatists abducted at least three principals whose schools had opened.

On the morning of April 30, principal Father William Neba of St. Bede’s College, in Ashing near Belo, North-West region, was reported to have been abducted while celebrating mass with students. He was released two days later. The school suspended classes on the day of the abduction.[52]

On May 25, 2018, in two separate incidents just days before the start of the national exams, the principal of Government High School Bolifamba Mile 16, Georgiana Enanga Sanga, and the principal of Cameroon Baptist Academy Muyuka, Eric Ngomba, were kidnapped.

In a video circulated online, Ngomba is seen sitting on the ground outdoors and surrounded by three armed men pointing weapons at his head as he is questioned. A voice off camera says that Ngomba was detained because he is the principal of a functioning school. The men prompt Ngomba to call on his fellow teachers and principals to close all schools “in this Amba region” and advise his colleagues not to administer the national exams. Both principals were released, Enanga unharmed, Ngomba with machete wounds.[53]

Attacks on Student and Teacher

Human Rights Watch documented one case in which a teacher was shot in the face in early 2018 in the North-West. A relative said she was found “in a pool of blood” shortly after the attack, adding that “now, she can only communicate by writing. She cannot chew, she can only eat soft food. The wound has not healed.” Her attackers were not identified or apprehended, but the relative explained that “she had received threats before because people were throwing tracts [written threats] at the school and even up to her house.”[54]

In another case documented by Human Rights Watch, Emmanuel Galega, a student, was shot and killed by people believed to be armed separatists who conducted an attack on a high school dormitory in Widikum on March 26, 2018. A man who lived in Widikum at the time of the attack told researchers the armed separatists had conducted two attacks against security forces in the weeks that led to the attack on the school. “People saw [the Ambazonian guys] come to the village that night. They went to the school because they had given information [to close the school] by dropping a note two months earlier. They came and went there and started shooting their guns. One child was shot,” he said.[55]

Arson Attacks on Schools

Ahead of the resumption of the school year in September 2017, media reported that unknown attackers partially burned over half a dozen schools at night.[56] The burning of schools, irrespective of their language of instruction, continued in a number of localities throughout late 2017 and early 2018. In June 2018, UNICEF reported that 58 schools had been damaged since the beginning of the crisis in the North-West and South-West regions.[57]

In general, these arson attacks occurred late at night or in the early morning. Claims of responsibility do not appear to have been left at the scene of attacks. However, a media report states that following an arson attack on the Government High School Bafut on May 8, 2018, a note was left calling for no schools to operate.[58] Government schools, non-denominational private schools, and Catholic, Presbyterian, and Baptist schools have all been targeted for attack.

For example, in one arson attack against the Presbyterian Secondary School Bafut in the early morning of November 1, 2017, three female dormitories for girls were set on fire, and many students lost their belongings in the blaze. A teacher from the school described the scene after the flames were put out, as parents rushed to the school to collect their children: “I could see the roofs of these dormitories were ravaged by fire and had burned down. And the walls of the dormitories were covered in smoke.”[59]

In another case, a father dropping his two children off at their kindergarten in Mezam division, North-West region, in February 2018, discovered that the school’s administrative block had been burned down over the night. The school closed for two weeks after the incident. “The teachers and the pupils are under great fear and panic,” said the father.[60]

The administrator of one partially burned school in August 2017 estimated the damage at 5.5 million CFA (US$9,800), including to school infrastructures, benches, books, and teaching materials.[61] He noted that enrollment dropped from around 325 students to just 77 following the arson attack. “We’ve never closed,” he said, adding, “No matter the crisis, children have a right to education.”[62]

Threats to Students, Parents, and Teachers

To enforce the boycott, separatist activists began to threaten the lives of teachers and children, and the burning of schools via social media, text messages, and printed notices (referred to locally as “tracts”). The aim was to ensure schools would not reopen or that children would not attend during the 2016-2017 school year, and the first half of the 2017-2018 school year.[63]

Sometimes the threats have been general, and at other times directed at individual schools, or at named individual educators. In at least one case documented by Human Rights Watch, one principal told researchers that one evening in December 2017 around 11 p.m., rocks covered in petrol were placed under his car and set alight. “The whole house could have burned,” said the principal, as his car was parked in a basement below his house. He had previously received a letter noting that he was a school principal with a demand of 500,000 CFA ($900) to support the separatist cause.[64]

As an example of the violent online threats, on September 5, 2017, a group that calls themselves “Ambazonia freedom fighters” posted on Facebook a photo of five identifiable children sitting at school desks, calling them examples of “betrayals,” and urging followers to “stone them.”[65] See figure 1 for another example of online threats.

Education officials told Human Rights Watch that printed notices were particularly common in late 2017 as some schools prepared to open, or opened, for the 2017-2018 academic year.[66] The same teachers reported finding such “tracts” left around towns, near schools, near teacher’s houses, and posted on electricity poles. Although the tracts are generally not signed by any individual or group, teachers we spoke with all attributed them to separatist activists. One example obtained by Human Rights Watch was written by individuals referring to themselves as “We Southern Cameroonians.”[67]

Such threats were often effective. One school administrator of a combined nursery and primary school in Kumbo told Human Rights Watch how one day in the first week of November 2017 there were printed fliers outside the school gate and slipped under the school door reading “Fire! Fire! Fire!” and warning that the school would be burned if it continued operating. “So we closed the gate, and did not open again until January [2018]. Some students still haven’t come back.”[68]

Negative Consequences for Children’s Education

Either because of these threats, or as a show of solidarity by parents and teachers with the separatist cause, or both, school enrollment levels have dropped precipitously during the crisis.[69] The majority of the schools across the North-West and South-West regions were closed for most of the academic year of 2016-2017. In May 2018, an estimated 42,500 children were still out of school according to OCHA.[70]

A father told researchers that he was keeping his secondary-school-aged daughter at home. “You hear of a child killed somewhere, of a teacher killed somewhere, of a school burned somewhere. You are not sure of the house you are living,” he said. “I don’t feel safe sending her.… She has been out of school for almost two years.”[71]

Some students have diverted to vocational trainings, such as in computers, information technology, sewing, and hairdressing.[72] But, as multiple educators told Human Rights Watch, many have stopped studying all together and stay at home or work.[73] Several interviewees expressed concerns about increasing pregnancy of teenage girls who are out of school.[74] “I saw six of my students are pregnant, they’re aged between 13 and 16,” one teacher from a rural government school told Human Rights Watch.[75]

Some worried that the longer students are out of school, the less likely it is they will return. “Children have tasted small money in jobs…so getting them back to school is going to be so difficult,” said one woman who worked for an NGO concerned with children’s education.[76]

“They don’t want to come to school again,” said the principal of a school that once had an enrollment of 485 students before the crisis, but only 45 when Human Rights Watch visited.[77] Other educators reported enrollment rates at their schools from 30 to 66 percent of pre-crises levels.[78] As of April 2018, some schools were still empty. For example, a school administrator for a number of schools in Bui division told us in April that at two of his schools “not a child has gone to school,” even though they had enrollments of 130 and 75 students prior to the crisis.[79] A teacher from a rural government school told us her school had enrollment of around 1,000 prior to the crisis, but as of April had only two students in attendance, because they were determined to take the national exams.[80]

The quality of teaching is also affected. One teacher at a government secondary school told us how she felt returning to a school, where the principal had received a visit from “some boys” who threatened him and told him to close the schools. “Going to teach [the following day] was like a nightmare for me,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I was looking more outside the window and door and not concentrating on teaching because anything could happen.”[81]

|

Safe Schools Declaration

Cameroon has not yet endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, an inter-governmental commitment by countries to better protect students, teachers, schools and universities during times of conflict. Many of its commitments could be relevant to ensure protection of education in the country. In particular, the Declaration encourages: · The collection of relevant data on attacks on education facilities, on the victims of attacks, and on the military use of schools and universities; · Investigations of allegations of violations of applicable national and international law and, where appropriate, the prosecution of the responsible perpetrators; · The development of conflict-sensitive approaches to education; · Ensuring the continuation of education even during conflict situations; · The re-establishment of educational facilities; and · International cooperation and assistance to respond to attacks on education. In addition, countries that endorse the Safe Schools Declaration commit to use Guidelines on Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, which contain suggestions on how to minimize the potential negative consequences when security forces are deployed to protect schools that have been threatened with attack. The Peace and Security Council of the African Union (AU) has called upon all AU members states to endorse the Declaration. In November 2017, Cameroon’s minister of basic education wrote to the Governor of the Far North calling for respect for the Declaration. |

III. Violations by Government Forces

Excessive Use of Force Against Demonstrators

Over a dozen victims and witnesses who spoke to Human Rights Watch described incidents between 2016 and 2018 where security forces, although equipped with anti-riot gear including shields, helmets, and tear gas, opened fire with live ammunition on demonstrators and bystanders.[82] In several instances, security forces brutally attacked or used excessive physical force against demonstrators, bystanders and other civilians.

Law enforcement officers should, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force. They should resort to the use of force only where such other means are ineffective or without any promise of success.[83] Where the lawful use of force is unavoidable, law enforcement officials should exercise restraint and ensure the degree of force used is proportionate.[84]

International human rights standards place stricter limits on law enforcement’s use of firearms than on the use of force in general. Law enforcement should use firearms only when necessary to defend themselves or others against an imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent the commission of a crime involving a grave threat to life, to arrest a person who is presenting such a danger and who is resisting their authority, or to prevent that person’s escape. The intentional lethal use of firearms is permissible only when “strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”[85]

On November 22, 2016, the media reported that security forces used tear gas and live ammunition and shot into crowds to disperse a teachers’ demonstration in Bamenda, killing at least one and wounding 10.[86] A 31-year-old painter who was at home that day told Human Rights Watch he was also shot: “Shooting began around 4 p.m. that day. I initially thought that it was tear gas,” he said. “But when I went out of my home to bring my motorcycle inside, I saw the police about 100 meters away on the main road. They began to shoot towards me. A bullet hit my left thigh and destroyed my superficial femoral artery,” he explained, showing researchers his medical records.[87]

On November 27, 2016, Buea university students who requested the administration to make English the only language of instruction at the university called on all Anglophone students to join the Bamenda teachers’ strike. Video and images captured during the following days show university students who took part in strikes being brutally beaten and abused by security forces who raided the campus, residence halls, and off-campus hostels.[88]

On December 8, 2016, protesters and security forces clashed along Bamenda’s Commercial Avenue and the Hospital roundabout during a visit by government officials. Protesters erected barricades and set government cars on fire. Security force personnel fired on demonstrators with live ammunition. According to Amnesty International, at least two unarmed protesters were killed that day, and several dozens were arbitrarily arrested, including children.[89]

A man shot in the leg on that day told Human Rights Watch that he left the demonstration when he saw that people were throwing rocks and security forces were firing live ammunition. “I was walking alone on the street when three police appeared in front of me. They said I shouldn’t have come.… As I started to explain I heard the sound of a gun and felt pain in my leg. The police then left,” he said.[90]

Another man said he witnessed a policeman shoot a demonstrator on that day: “I saw the [police] pointing the gun because the people were throwing stones. I saw one put a bullet into one guy next to me. He was shot in his chest. So I had to run.”

During the 2017 wave of protests, government security forces deployed to larger hubs such as Bamenda, Kumba and Buea also used live ammunition against protesters and bystanders, killing at least a dozen civilians and injuring scores, according to Amnesty International and international media reports.[91]

On October 1, 2017, as separatist activists demonstrated in the South-West and North-West regions to celebrate the declaration of independence of the “Republic of Ambazonia” in defiance of bans on protests and curfews imposed by the two regions’ governors, several unarmed people were shot by security forces, according to witnesses who spoke to Human Rights Watch in both regions.

A health professional told Human Rights Watch in Kumbo that the hospital where he works received several people wounded by bullets in the run up to the October 1 demonstration as well as on that day. “We received a young girl, Ailue, who got a bullet in her eye when she was in her room,” he said. “The bullet took out her septum and the concha of her eye but it didn't touch her brain. Most of the other wounded had received bullets in their lower limbs.”[92]

On October 1, in Buea, security forces killed two friends in separate incidents: a 34-year-old technologist who had studied in India and Norway and a 39-year-old lawyer and father of two. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, the technologist’s parents said that they began to hear gunshots in the early hours of the morning. Their son decided to leave home in the early afternoon to meet with friends as the situation appeared to calm down, and was shot on the street, near his home.[93]

“When we heard the gunshot, we ran and saw the blood was pumping like water. Our son was shot three times, in the foot, the stomach and the leg. We got to him while he was still alive,” his mother told Human Rights Watch. “He saw me as I was crying and he started to cry too. He said: ‘May God send somebody to replace me in the family – I don't know what I have done – God, let you take my soul so that I can rest.’ Before we reached the hospital, he stopped talking.”[94]

The same day, a 43-year-old man with a physical disability was killed by security forces outside his home in Bamenda. “The police came around 9 a.m. with a car and everybody ran but he couldn’t because he only had his right leg. His left leg was a prosthesis,” his wife told Human Rights Watch. By the time she got there, she said, her husband’s body was gone. He was brought to a mortuary by the police in the early hours of morning, the following day. She said that her husband’s death was never investigated.[95]

Human Rights Watch also obtained 27 different written denunciations made to a local non-governmental actor of violent security force abuses during raids of private homes in the North-West region in the days that followed the September 22 and October 1 demonstrations, roughing up people, including women, and destroying TVs, computers, satellite receivers, motorbikes and other property.[96]

On October 1, 2017, two members of the security forces raided a home in the North-West region where two women were hiding. One of them, who spoke to Human Rights Watch, said the men beat them. “They took us outside and one of them hit my cousin’s wife on the forehead with the bottom of his gun. The other took a piece of broken glass and cut open my right arm,” she explained. Six months later, as researchers saw, her arm still hadn’t properly healed.[97]

In the early hours of the following morning, security forces beat a man with an intellectual disability in Kumbo. His friend, who described the event to Human Rights Watch, said that security forces intercepted him on the road and asked him to remove everything from his bag.[98]

“Then they poured water on him and beat him with guns, irons and finally undressed him completely, until he was naked. They then beat him with iron sticks and dislocated his arm and hand,” he told researchers who were able to examine the man’s scars. Security forces then took him to the main gendarmerie station at Tobin but someone realized he had a disability and he was brought to a nearby hospital.[99]

“They just threw him in front of the hospital and left. The staff collected him but he remained unconscious until the next day,” his friend added.[100]

Torture and Extrajudicial Executions

Human Rights Watch documented three cases where security forces detained people suspected of supporting the secessionist cause, and then tortured and killed them in detention. In a fourth case, Human Rights Watch analyzed evidence of torture filmed by perpetrators, who appear to be gendarmes.

On January 29, 2018, security forces beat to death 22-year-old Fredoline Afoni, a third year student at the Technical University of Bambili who had returned to Shishong, near Kumbo, to visit his uncle who raised him. “Fredoline was working at home when he received a phone call from an unknown number. The person told him to come and pick up some luggage at a nearby junction. He went there,” a close relative told Human Rights Watch.[101]

“When he arrived there, he was picked up forcefully by guys dressed in civilian clothes and taken into a Prado truck that I have often seen at the gendarme station in Tobin,” the uncle explained. Sometime later, a vehicle from the security forces passed through the same junction, with Fredoline sitting in the back of the pick-up, naked and handcuffed. “They drove to his grandmother’s house, near mine. A girl saw them and said he was already badly beaten up. They collected his laptop and cellphone and drove away again.”[102]

Informed by neighbors of Fredoline’s arrest, the uncle proceeded to the gendarmerie and was told that Fredoline was in their custody and that he should come back in the morning. The next day, he was informed that Fredoline had died. “I only found out where his body was three days later. The gendarmes had just thrown his corpse outside the mortuary in Jakiri, out there in the open, with no respect. He was naked and his body was already decayed, with cracks all over,” the uncle said.[103]

A medical professional who later examined the body told Human Rights Watch that Fredoline had died as a result of being beaten. “The body had broken ribs – when you touch it you can hear it – and blood had come out of the anus,” he said. “He had been badly beaten.”[104]

In another case, on February 1, 2018, men dressed in civilian clothes but wearing military boots and believed to be security forces shot Ndi Walters at his shop in Bamenda’s car market and took him away. “Unknown armed men inside a red Corolla shot him and took him away in their car. They drove for 100 meters and then came back to the shop to pick his phone and laptop. Lots of people saw them and called me when it happened,” his brother told researchers.[105]

“I went to all the police stations in town and they did not know where he was or who had him. A week later, I went to the mortuary and found him there. The mortuary said that the body had been delivered by a military truck.” According to the brother, an autopsy ordered by the state council concluded that the young man had died from hard blows to the chest and forehead.[106] According to his Facebook profile, the young man had been actively supporting the secessionists online.[107]

In a third case various interviewees told Human Rights Watch that in early February 2018, security forces arrested, tortured, and then sliced open the neck of Samuel Chiabah, a 45-year-old father of five popularly known as Sam Soya, in retaliation for the earlier killing of two gendarmes by armed separatists at a checkpoint between Bamenda and Belo.[108]

According to media reports, the day after those killings, security forces raided homes in Belo, some 15 kilometers away from Mbingo, and beat up and arrested residents.[109]

A video and photos taken by security forces and analyzed by Human Rights Watch began to circulate on social media showing the interrogation of two men, including Sam Soya, sitting on the floor being questioned about the killing of the two gendarmes. Sam Soya is heard crying in agony and denying participation in the murders while the other man accuses him of having known about the attack.[110] The photos, taken later, show members of security forces in uniform using a knife to cut open Sam Soya’s neck and the leg of the other man, both of whom are lying face down on the floor and in handcuffs.[111]

On May 12, 2018, another video taken by security forces began to circulate online. It showed a suspected armed separatist leader, allegedly named Alphonse Tobonyi Tatia, being subjected to intense beating by men wearing gendarmerie fatigues. As the man lays face to the ground in the mud with his arms handcuffed in the back and his legs immobilized by a chair posed over calves, gendarmes brutally whip his bare feet with the flat side of a machete. As he cries in pain, the gendarmes heard on the video call him “commandant,” ask “you are general?” tell him “you don’t kill gendarmes, non!”[112]

Three days after the release of the video, the Ministry of Defense issued a communiqué in which it acknowledged that men in uniforms had “manifestly gone beyond the legal norms and techniques used in such circumstances” and pledged to investigate the incident and punish those responsible.[113]

International human rights law absolutely prohibits torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.[114] Furthermore, governments are under a positive obligation to effectively investigate all allegations of ill-treatment by law enforcement personnel and hold those responsible accountable.[115] Unlawful killings carried out by state agents are considered extrajudicial executions, a grave violation of international human rights law.

Treatment and Extortion of Detainees

Since the beginning of the crisis in November 2016, security forces have arrested hundreds of demonstrators, bystanders, and other civilians suspected of supporting the secessionist agenda, according to international monitors.[116] Human Rights Watch documented one 2016 incident where demonstrators were arrested en masse, beaten and kept in detention for about a month before eventually being released by presidential order. In one case, civilian detainees accused of violating the curfew were reportedly presented in front of military courts.[117] In another, security forces detained two older people in proxy for their grandson.

In one example, on December 8, 2016, a dozen protestors were arrested from the Bamenda hospital, where they had sought refuge from security forces who used live bullets to disperse the crowd. Five people detained at the time told Human Rights Watch they were beaten with sticks and guns and transferred to Yaoundé where they were detained for several weeks in poor, overcrowded and unsanitary facilities.

One of them, a 24-year-old mototaxi driver, described how security forces beat him and the dozen others detained at the time of their arrest, including three children aged between 14 and 16. “They told us to come out [of the building] and lie down on the ground. Then, they started to hit all us with a black stick all over our body. The children too,” he said.[118]

The dozen detainees arrested at the hospital were then forced to lie down on top of one another in the back of a security forces’ pick-up and were driven away to a gendarmerie station. Another former detainee also arrested at the hospital said he arrived at the station with his head bleeding from the beating. The next day, he explained, several dozen people arrested on December 8, were transferred by plane to Yaoundé and those from the hospital were taken to a hall in a security forces base. “The place was very big. There were offices outside. Police were ‘GP’ – presidential guard. We were there for two weeks. Nobody could even bathe,” he said. “We ate once a day. Rice. Then they took our real statement. They questioned us and say that we were ‘Anglo fools’ and called us other names.”[119]

On December 23, 17 Bamenda detainees were taken to the state counsel, questioned about their treatment, and promised that they would soon be released. The three children who had been arrested were released while the others were taken to Yaoundé’s Kondengui Central Prison.

There, the Bamenda detainees described being taken to an “initiation cell,” the “Salut de Passage” where all new detainees are held together for a few days, which was severely overcrowded. One former detainee told researchers that there were “more than 70 people inside. You could not sit or move, just stand against one another. There was no windows and it was very hot inside. No way to relieve yourself.”[120]

The following day, the detainees were dispatched in the “Kosovo” quarters of the prison. “The prisoners were so rough. They do evil things there. It is very dirty. You see people fighting.… Someone comes and says ‘You’re from Bamenda’ and they start a fight,” one of the former detainees told Human Rights Watch. ”We spent Christmas there.”[121]

On January 9, 2017, 21 of the Bamenda detainees were released by presidential order. They were taken by bus from Yaoundé’s Kondengui Central Prison back to Bamenda. “Now, I feel pain in my chest at times, especially at night. It started when I was in prison,” he said.[122]

Most former detainees who spoke to Human Rights Watch said authorities asked for bribes for their release. The same month the Bamenda detainees were released, a 40-year-old librarian was arbitrarily arrested at a roundabout near a gendarmerie station in the North-West region, accused of supporting the opposition and beaten prior to being transferred to Yaoundé.

“When I got to Yaoundé, an investigator met with me and said that I had no problem and that I could go back if I gave him 400,000 CFA (about $700),” the man told Human Rights Watch.[123] He did not have the money, but instead of accepting less, the investigator recommended he go to prison. He spent eight months at the Kondengui Central Prison prior to his release following a mass September 2017 presidential amnesty.[124]

In another case, a 48-year-old man, arrested at home in October 2017 on suspicion of participation in the protest movement, had to sell his land in order to pay a security force commander an 800,000 CFA (about $1,500) bribe to release him after 2.5 months in abusive detention conditions in Yaoundé.[125]

In another case in the North-West region, in February 2018, a gendarmerie commander asked a 30-year-old single mother of two to pay 250,000 CFA (about $450) to release her disabled 88-year-old father and her mother who were detained as proxy for her nephew, suspected of being an armed separatist. She said that while she was out working in the field, security forces came looking for her nephew but found and arrested the two older persons, prior to setting the family home on fire.[126]

“They came to the house that I took 10 years to build. They came and burned our compound. Everything was burned,” she told researchers. “Now, I live in misery. I am lost. I have no job, no money, no house, no food, no clothing. I used to stand strong, but this one… I feel psychologically defeated. I don’t know where to start.”[127]

Attacks On Villages: Burning and Killings

In late 2017, armed separatists began to operate more visibly in small, rural localities in forested areas of the South-West region, leading government security forces to patrol backcountry roads more frequently to try and assert control more aggressively.

As of June 11, 2018, the government said armed separatists had killed 32 soldiers, 42 gendarmes, 7 police officers, 2 prison wardens and 1 eco-guard in 123 attacks since the beginning of the crisis. In some cases, according to the government, bodies of security forces personnel were found mutilated or beheaded.[128]

In an interview with French media in late December, Brigadier Melingui Nouma, at the time the army commander of the South-West region, accused the separatists of engaging in guerilla warfare and claimed that they were being trained by foreigners.[129]

Faced with a seemingly invisible enemy, patrols of security forces composed of army, gendarmerie and police began to carry out abusive counter-insurgency tactics in the two North-West and South-West regions.[130]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 16 displaced people from eight villages located in three different divisions in the South-West region who all described similar patterns of abuses by security forces. These include killings of unarmed civilians, including older people and people with disabilities, beatings, arrests, and the occasional wholesale burning and destruction of homes and property.

In attacks on twelve villages in six administrative divisions of the South-West and North-West regions by security forces between January and April 2018 and documented by Human Rights Watch, security forces allegedly shot and killed over a dozen civilians, including at least seven people with intellectual and/or psychosocial or physical disabilities who did not flee at the time of the attack because they were unable or refused to. Four older women were also left behind by their relatives at the time of the attack and were burnt alive in their houses, according to witnesses.

In most cases, villagers said that the attacks took place in retaliation for earlier attacks by separatist forces against security forces or because of rumors of separatist presence in the villages. In all cases, the bulk of the population fled to the bush when the security forces arrived. Witnesses described seeing plumes of black smoke coming from the village shortly after.[131]

|

Satellite and Video Verification

Human Rights Watch has assessed a total of 131 villages via satellite imagery for evidence of building destruction in the subdivisions of Mbonge, Kumba, Ekondo Titi, Konye, and Nguti, in the South-West region. Of this number there was evidence of building destruction in 20 villages and small towns consistent with burnings carried between January and June 2018 according to satellite imagery analysis. To date, several hundred destroyed buildings have been identified in the affected villages. As of June 2018, building destruction was ongoing. Human Rights Watch experts have also analyzed videos originating from the North-West and South-West regions to identify the precise location in which they were filmed. The videos, largely posted online on platforms like YouTube and Twitter, were filmed by people who have witnessed the aftermath of the destruction of buildings and villages or in some cases by the security forces’ personnel involved. The geolocation verification process centers around matching what can be seen in the video with what can be seen in satellite images. By identifying distinguishing features – a bend in a road, different types of trees, shadows casted from buildings, or the shapes and colors of roofs – in both the video and the aerial image, the verification process enables researchers to confirm where the video was shot. Human Rights Watch experts focused on geolocating videos coming from four villages: Kwakwa filmed in January 2018; Azi filmed in April 2018; Munyenge filmed in May 2018; and Ekona Mbenge filmed in June 2018. Through applying geo-location techniques to these videos Human Rights Watch verified that these videos are filmed in Kwakwa, Munyenge, Ekona Mbenge, and Azi. While this process confirmed the location, it was also important to verify that these videos were not filmed months or years before the incident was reported to have taken place. This involved confirming that they were not uploaded online before the date that the destruction was said to have taken place and finding other images and videos to corroborate them. This process can further corroborate claims of villages and buildings being destroyed and being able to state that these videos and what they purport to film are authentic. |

The army has sought to minimize, but not deny, allegations that they burned homes. In a late April 2018 interview with Agence France Presse (AFP), Brigadier Donatien Melingui Nouma, the South-West region military commander, said that the army was struggling to quell the rising insurgency by armed separatists and said that the army “only burns those houses where we find weapons.”[132]

In meetings with Human Rights Watch, senior government officials expressed doubts that security forces had committed burnings on a large scale. In its Emergency Humanitarian Assistance Plan in the North-West and South-West regions published on June 20, the government however budgeted for the reconstruction of 10,000 destroyed family homes, thereby indirectly recognizing the destruction of hundreds of houses.

In May 2017, OCHA estimated that up to 160,000 people were internally displaced in the South-West and North-West regions, with 80 percent of them hiding in the forest.[133]

Kwakwa, January 18, 2018

In early 2018, security operations began to intensify in Meme division, a densely forested area in the South-West region. On January 7, armed separatists attacked and killed at least one member of the security forces in Kwakwa’s neighboring village of Kombone, in Meme’s Mbonge subdivision. The killing prompted a retaliatory operation by security forces in Kombone in which they burned half a dozen houses and reportedly killed two civilians.[134]

On January 14, 2018, separatists in Kombone detained two military men travelling on the Mudemba-Kumba road then allegedly killed and beheaded one of the men.[135] The next day, three witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces attacked Kwakwa village, robbing and setting houses on fire. “That day, security forces came to Kwakwa and we all ran to the bushes,” a 28-year-old student told researchers. “When I came back from the bush, I saw that they had broken the doors of our house and stolen my money, clothes and TV,” he added.[136]

Another man who fled to the bush at the time of the attack said that houses were set ablaze by security forces that day: “I returned late at night to the village and saw that everything had been broken in my house. They had also opened our kitchen’s gas canister and let the gas run out inside the house. Five big houses were burned and three bars,” he said.[137]

Security forces returned to Kwakwa on January 18 and burned hundreds of houses and killed at least seven civilians, including three people with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities and two older women burned to death in their homes, witnesses who fled the attacks and returned to the village hours later told Human Rights Watch.[138] Videos filmed in the village after the attacks show the burned body of an older woman and those of three men while satellite images collected by Human Rights Watch highlight extensive destruction.[139]

“They came back and burned all of the houses. The only things left were the church, the health center and some houses. Most of the houses are built with wood planks,” a 34-year-old man who fled the attack told Human Rights Watch.[140]

Since the attack, a displaced villager from Kwakwa told researchers most of the population lives in the bush, afraid of new attacks, without access to food or services. “No NGOs have come. People stay between 1.5 and 5km from the road to be safe if there are any stray bullets. So people only eat cocoa nuts and plantain.”[141]

Bole, February 2 and March 23, 2018

Around 11:30 a.m. on February 2, 2018, security forces attacked the Bole village, in the South-West region’s Meme division, Mbonge subdivision, and immediately began to shoot, three witnesses told Human Rights Watch.

A 45-year-old clergyman who lived by the road told researchers that they were many and well equipped: “The soldiers, gendarmes and BIR came with two armored cars mounted with guns. They had other vehicles but I couldn’t count them. They started to shoot,” he said.[142]

While many civilians immediately fled the village for the bush, several were killed by security forces. “They started to shout that the security forces were coming so all of us ran to the bush. They also shot my uncle Divine outside his home in the ear. In total, they killed about 8 people,” a 24-year-old woman told Human Rights Watch.[143] Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that among those killed were a 19-year-old and an elder.[144]

Three witnesses also described another attack on March 23, 2018. A 43-year-old man who lived in Bole with his family was on his way back from Mbonge when he encountered the security forces and saw them setting homes on fire. “The security forces blocked us at the bridge. Suddenly, I saw a huge cloud of smoke and realized that Bole was being set on fire. Amidst the smoke, there were sporadic gunshots,” he told Human Rights Watch.[145]

“The next day, when I moved forward, I found that everything in the house was burned, including my mother. When the military came, my wife and children ran but my mother couldn’t,” he said. “She died a terrible death. We only found her head and intestines. Everything else was burned.”[146]

Wone and Dipenda Bakundu, March 2, 2018

In another attack documented by Human Rights Watch, three witnesses described how security forces arrived in the area of Wone village after armed separatists burned a timber truck operating along the crucial Kumba-Mamfe road in the South-West region’s Koupe-Muanengouba division.

A 28-year-old witness interviewed by Human Rights Watch described how as she fled the village following the attack on the timber truck, she heard government forces arriving and saw smoke rising from the village:

On March 2, around 6 a.m., the Ambazonia boys came to Wone, put fire to a timber truck going to Kumba and kidnapped the driver. I immediately returned home and left with my children and husband to the bush. As we ran, we heard gunshots and loud detonations. When in the bush, we saw a big fire, the whole place was red with fire and then we realized that [security forces] had put fire to our houses.[147]

Another witness who had just returned to Wone that morning saw the security forces arrive, including members of the Rapid Response Battalion (BIR), a force that has received significant material and training support from the US and been alleged to commit torture and other abuses.[148] “They came with three trucks and two land-cruiser. They were masked and had BIR written on their trucks. They paraded up and down and then all of a sudden I heard gunshots,” the 33-year-old father of three told researchers. “I later heard that the BIR split and some of them went towards Dipenda Bakundu, [the neighboring village] and were ambushed on their way there. They burned Dipenda Bakundu and then came back,” he said.[149]

An older woman who fled the village said her house in Wone was among those burned:

After we came back to the village, all houses were burned. My house too. Now I sleep under trees in the bush,” she told Human Rights Watch. “In my entire life, this is the first time that I have to flee my house. When peace comes back and they say that we can come back to our village, where will we stay now that they have burned our house?[150]

Mongo Ndor, April 3, 2018

Another government attack took place a day after government forces claimed to have rescued a group of 12 European tourists allegedly kidnapped by armed separatists in the South-West region’s village of Mongo Ndor on April 2, 2018.[151]

Two women from Mongo Ndor told Human Rights Watch that security forces attacked their village the following morning and burned their homes. Images analyzed by Human Rights Watch show that approximately 80 percent of the village was burned.[152]

One woman told researchers:

The morning after the white people were here, I heard a big BOOM – the noise was too much. So I ran to the bush with my children until my mouth was dry. Then around 2 p.m., other people in the forest began to say that the houses were burned. When we went back to the village. Everything was burned to ashes, Mami Maria was burned inside her home. She had diabetes and couldn’t walk very far. Everybody was just crying.[153]

V. Acknowledgments

This report was written by Jonathan Pedneault, researcher with the Emergencies division of Human Rights Watch and Bede Sheppard, deputy director of the Children Rights Division, based on research conducted by Pedneault and Sheppard in the North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon in April 2018.

Josh Lyons, satellite imagery analyst, provided analysis of satellite imagery. Gabi Sobliye and Hadi al-Khatib, consultants with the Emergencies division provided video geolocation verification and analysis. Michelle Lonnquist, senior associate with the Emergencies division of Human Rights Watch and Alex Firth, associate with the Children Rights division, conducted additional desk research.

This report was reviewed by Jehanne Henry, associate director in the Africa division. Philippe Bolopion, deputy director for Global Advocacy, Kriti Sharma, researcher with the Disability Rights division and John Fisher, Geneva director reviewed the report and contributed to the recommendations. Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, and Chris Albin-Lackey, senior legal advisor, provided program and legal reviews.

Michelle Lonnquist prepared the report for publication and provided editing and formatting assistance. Production assistance was provided by Jose Martinez, senior coordinator, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Multimedia production was coordinated by Connor Seitchik and Will Miller, multimedia producers.

Human Rights Watch would like to thank all the courageous women and men who agreed to tell us about their experience and its impact on their lives and those of their loved ones.