Workers in the Shadows

Abuse and Exploitation of Child Domestic Workers in Indonesia

I. Summary

I started work when I was 11 years old…. I worked as a babysitter for my first employer. The male employer shouted at me a little too often…. The employer wouldn't let me leave the house.... I made the baby porridge, gave him milk, carried the baby if he cried, changed the baby, put him to sleep, and played with the baby. When the baby slept I did the ironing…. I woke up at 5 a.m. every day, and worked until 7 p.m.

- Ayu, 13 years old, Bandung

Every day my employer was angry and she would kick me and pinch me. Almost every day. When I mopped the floor, I did not use a mop for mopping, just my hands and a rag, and then my employer kicked me to go deeper under the bed. She would pinch me on my shoulders.

- Ratu, 15 years old, Yogyakarta

The Indonesian government is failing to protect some of the nation's youngest workers from abuse and exploitation. Hundreds of thousands of girls in Indonesia, some as young as 11, are employed as domestic workers in other people's households, performing tasks such as cooking, cleaning, laundry, child care, and sometimes working at their employers' businesses. These girls live and work in the shadows of society: hidden behind the locked doors of their employers' homes, isolated from their family and peers, and with little regulatory oversight by the government. Indeed, many Indonesian government officials deny that these children are even really workers.

In 2005 Human Rights Watch released Always on Call, a 74-page report documenting the endemic exploitation and abuse of child domestic workers in Indonesia. Girls described being lured with false promises of higher wages in cities without full details about the tasks they would perform, the hours they would be expected to work, or their inability to attend school. Most girls said they typically worked 14 to 18 hours a day seven days a week, with no day off. Many told us that their employers forbade them from leaving the house where they worked, isolating them from the outside world and thus placing them at higher risk of abuse with fewer options for finding help.

We also documented how many employers withheld paying any salary until the child returned home-and that many employers failed to pay the children at all or pay less than what they promised. The tactic of withholding the salary deters child domestic workers living far from their homes from leaving exploitative situations. In the worst cases, we found that girls were physically, psychologically, and sexually abused by their employers or their employers' family members, in addition to being exploited for their labor.

In 2008 Human Rights Watch returned to Indonesia to assess developments since the original research. Three years on, the situation for child domestic workers remains deeply disturbing. They continue to endure the wide range of abuses documented extensively in 2005.

The main focus of our research, however, was the policies and actions of the national and local governments. Despite some limited progress in a few areas-for example, the creation by the police of dedicated women's and children's units at provincial and some district levels and the passage of an Anti-Trafficking Act by the legislature-the overall official response remains seriously lacking in substance, coherence, and urgency. The failure to implement effective protection means that national and local governments are responsible for allowing child domestic workers to be exposed to abuse and exploitation.

A fundamental problem in officialdom is a pervasive attitude of denial. Despite the widespread nature of abuses, during our research we found that many government officials consistently denied that child domestic workers are exploited or abused. Most officials attempted to refute examples of abuse that we presented to them by claiming that there were only a handful of extreme cases that therefore did not require fundamental changes in the government approach.

Our research demonstrates that many assertions commonly made by government officials to justify their inaction with regard to enacting better protections for child domestic workers do not stand up to scrutiny, and are simply myths. In Chapter V of this report we use our research to tackle some of the most enduring myths head-on.

For example, many officials insisted that children engaged in these activities were not even workers, but merely "helpers." Yet our research shows that child domestic workers do indeed carry out activities that are taxing, productive, and deserving of being recognized as work, not just "help." Indeed, long days of demanding labor can be such hard work that it makes some child domestic workers physically ill.

Other officials insisted that child domestic workers were treated "like family" by their employers. But our research demonstrates that employers frequently recruit child domestic workers through commercial recruitment and placement agencies, or rely on local vendors who draw upon their own personal connections. In this way, any kind of familial or personal connection or affiliation between the employer and the child domestic worker is lost. In the vast majority of cases the primary concern of employers is the maintenance of their households, not the personal development of their employee, so the relationship between employer and child domestic worker is commercial, not familial or personal. Moreover, the motivation of an employer who recruits a child rather than an adult is often to find someone who will work for less, who will complain less, who is easier to order around, and who has fewer social connections. These factors are also likely to make the domestic worker more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation and less able to protect herself.

Some government officials claimed that the work conditions of domestic workers simply cannot be feasibly monitored or regulated, and therefore there was little more that the government could do. However, it is not that inspections and monitoring are impossible to implement-rather it is that the government simply chooses not to prioritize the protection of these young workers. For example, our research revealed that even basic telephone hotlines that children could use to report abuse and seek assistance are not answered or adequately staffed.

Officials also tended to prefer to favor employers' convenience and luxury over recognizing child domestic workers' rights. It was suggested, for example, that child domestic workers could not be given a minimum wage like other workers because it was more important that a greater number of employers be able to afford to hire a domestic worker. Yet such arguments ignore that the government is obliged to protect all individuals from exploitation and abuse. To the extent that policymakers believe that more families should be able to access assistance with domestic work or child care, then the government should instead consider pursuing alternative policies-such as affordable community child care, making workplaces more flexible for working parents, or more generous maternity and paternity leave-that do not depend on the exploitation and under payment of child workers.

We were also told that encouraging the provision of written contracts might intimidate employers to such an extent that they would not even hire a domestic worker. But the negotiation and conclusion of written contracts detailing the rights and obligations of both employer and employee can be beneficial to both parties, as the process helps clearly define the relationship in advance and can serve as an important point of reference. The creation of a standard "model" contract could help alleviate anxieties over the use of written agreements.

Government officials also attempted to argue that restrictions on the maximum number of hours that someone can be required to work-as guaranteed to other workers-could not be extended to child domestic workers because domestic work was exceptional in not being a "nine-to-five" kind of job. It was similarly suggested that child domestic workers did not need days off. Indeed, it was questioned whether domestic workers would even know what to do if granted one day off a week like other formal workers. These arguments ignore the fact that regulating maximum work hours and a weekly day of rest allow governments to meet their obligation to protect workers' rights to just and favorable work, health, and rest. No employee can be required to be constantly at the beck and call of his or her employer. If an employer genuinely requires around-the-clock assistance, then a second or third shift should be hired to cover. Excessive work hours and lack of rest days directly affect the health and growth of children. Children also require time to contact and connect with their own families, so as to prevent feelings of isolation and resulting psychological problems. A day off for domestic workers is also an issue of safety for employers and their families, as everyone performs better and with more care when given adequate rest.

These myths endure because of a general ignorance about the conditions faced by many child domestic workers, which results from a lack of government monitoring and inquiry into the lives of child domestic workers, and from continuing discriminatory attitudes about the role of girls and women in society. Dismissive attitudes and misconceptions can be a key impediment to the enforcement of existing laws, and are a serious obstacle to the creation and implementation of better regulations and policies.

It is particularly disturbing that such attitudes appeared to be rife in the Ministry of Manpower, the government ministry with lead responsibility for investigating the labor exploitation of children and drafting legislation protecting domestic workers. Officials in the ministry did not seem to recognize the existence of the abuses they are supposed to take action to prevent. Their failures are obstructing the efforts of other concerned parties, official and non-governmental, that do recognize the special vulnerability of child domestic workers.

While Indonesia has legislation intended to guarantee the rights of children, and has started initiatives to provide for their protection, these remain contradictory, incomplete and, above all, inadequately implemented.

In particular, the Indonesian government's ongoing failure to reform discriminatory labor laws makes child domestic workers vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. The exclusion of all domestic workers from the basic labor rights afforded to formal workers by the Manpower Act of 2003, the nation's labor code-such as a minimum wage, overtime pay, an eight-hour workday and forty-hour workweek, weekly day of rest, vacation, and social security-has a discriminatory impact on women and girls, who constitute the vast majority of domestic workers. This exclusion in the law also serves to perpetuate the devaluing of domestic work and domestic workers.

Two laws that offer the potential to deliver genuine protection to child domestic workers are the Child Protection Act of 2002 and the Domestic Violence Act of 2004. The Child Protection Act provides stiffer penalties than available under the criminal code for economic or sexual exploitation of children, and for violence against children. The Domestic Violence Act prohibits physical, psychological, and sexual violence against live-in domestic workers. The law also lowers the evidentiary standard necessary to prove the relevant crimes in court. While the police and prosecutors have finally begun prosecuting individuals under these two laws-a positive change from the situation in 2004-there is still more to be done to enforce these and other laws intended to protect children and domestic workers from abuse. Increased awareness of these laws by the general public, labor recruiters and suppliers, prosecutors, and the courts would assist in these efforts.

At the provincial and district level, local initiatives-such as Central Java's new provincial law that cites domestic work as an example of the worst forms of child labor-offer the potential for incremental progress. The decision, however, by the Jakarta local government in 2004 to rescind what had been one of Indonesia's most progressive pieces of legislation for the protection of domestic workers is seriously lamentable. The suggestion that these labor protections were scaled back in response to the government's unwillingness to budget the relevant agencies with the necessary resources and training to fulfill their duties under the previous law is also disappointing.

There are a few examples of progress being made to improve the situation facing child domestic workers. One is the 2007 Anti-Trafficking Act which, although falling short of international standards, could represent a contribution to the protection of child domestic workers-but only if the government follows through with an appropriate public awareness campaign and prosecutions of persons alleged to be responsible for trafficking.

Another positive development is the recent move by the police to establish a dedicated women's and children's unit in all provincial police stations, and in many district police stations. While this move has yet to produce demonstrable widespread change, it offers promise-but, once again, only if provided with adequate resources and support.

However, the police also need to do more to protect child domestic workers and to prosecute those who perpetrate crimes against them. Many victims and witnesses remain reluctant to approach the police out of concerns that the police will be unsympathetic, uncooperative, ineffective, or corrupt. It is the responsibility of the police to correct these perceptions through better and more gender- and child-sensitive performance. The police often take a very passive approach to cases involving domestic workers, for example, by placing the burden on victims to find witnesses or supporting evidence, and not pro-actively investigating reports of possible abuse, including economic exploitation. Labor exploitation and violence against domestic workers is a criminal issue, and the police should investigate allegations of abuse and prosecute whenever there is credible evidence that an employer has committed a criminal offence-even if the parties have attempted to reach an informal settlement through the payment of some money by the employer to the victim.

Police procedures need to be urgently reformed in order to effectively respond to allegations of abuse and exploitation made by domestic workers. In particular, police should provide temporary protection to a victim within 24 hours of receiving a report of violence in the household, and improve their response times in commencing investigations in response to complaints filed by domestic workers.

Both police and Manpower officials should perform their current duties to enforce existing labor regulations. Prosecutors could also do much more to respond in a gender- and child-sensitive manner to the concerns and needs of domestic workers who are victims of abuse. Prosecuting crimes committed against child domestic workers sends an important message that society will not tolerate its children being abused and exploited in the worst forms of domestic labor.

Indonesia's National Plan of Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor identified children who are physically or economically exploited as "domestic servants" along with twelve other areas of child labor, as a worst form of child labor. In 2008, the plan entered its second five-year phase, during which time the plan commits to eliminating the worst forms of child labor in this sector. But assessments of the success of the first five-year phase of the action plan have been mixed, and provincial and district action committees that have been established to carry out the plan appear to vary in their effectiveness and enthusiasm to work.

Direct and indirect school costs often force children to drop out of elementary and junior high school before they complete their compulsory nine years of schooling, and this is a contributing factor to children being pushed into the labor force. Increasing the ability of poor children to access educational and other vocational training opportunities would greatly reduce the number of children being pushed into domestic work at a young age.

Change is possible when the relevant government officials choose to prioritize stronger protection for child domestic workers. In 2010, members of the International Labor Organization, including Indonesia, will meet to discuss a proposed new international treaty on providing decent working conditions for domestic workers. The fact that Indonesian citizens are among the tens of thousands of domestic workers subjected to abuse in other countries is recognized by the government, among other ways through the creation of a special police clinic for women who return to Indonesia with injuries caused by abuse. However, only if Indonesia is also seen to be recognizing and taking action against the abuse of domestic workers at home, including child domestic workers, will advocacy for the protection of Indonesian domestic workers abroad have any credibility. Indonesia must act fast to get its own house in order, rather than risk earning the reputation of being one of the poorest protectors of child domestic workers.

Key Recommendations

A full and detailed set of recommendations can be found in Chapter VIII of this report.

To the president and the national parliament

- In order to be in conformity with international legal standards prior to the 2010 ILO Conference on Decent Work for Domestic Workers, pass a Domestic Workers Law by the end of 2009 that:

1.Guarantees that domestic workers receive the same rights as other workers, such as a written contract, a minimum wage, overtime, a weekly day of rest, an eight-hour workday, rest periods during the day, national holidays, vacation, paid sick leave, workers compensation, and social security.

2.Requires employers and labor agents who recruit and place domestic workers to verify the age of prospective domestic workers by reviewing and maintaining copies of the employees' birth certificates or junior high school graduation certificates.

3.Prescribes the maximum number of hours children aged 15 and older, including those in the informal sector, may work to enable working children access to basic education and higher secondary education, including vocational training.

4.Stipulates minimum conditions of housing arrangements, provision of food, and protects domestic workers' freedom of movement and communication.

To provincial and district governments

- Strictly enforce 15 as the minimum age of employment for all employment sectors, including domestic work. The only exception to this rule is for children age 13 and 14 engaged in "light" work who, under the limited conditions elaborated in the 2003 Manpower Act, may work for up to three hours a day. Prioritize underage domestic workers for removal and recovery assistance to help them rebuild their lives.

- By the end of 2010, enact regulations that:

1.Require employers to register the name and age of each domestic worker working in their homes with the local labor agency or another appropriate local authority.

2.Require labor inspectors or other designated inspectors to monitor labor supply agencies and workplace conditions, and that authorize inspectors to monitor private households, conduct unannounced visits, and interview domestic workers privately about working conditions.

3.Ban abusive employers from hiring domestic workers in the future and ban recruiters who have engaged in unethical practices from recruiting domestic workers.

- Provide labor inspectors or other designated inspectors with the resources and training necessary to effectively monitor child labor in hidden work situations, including child domestic labor, and to refer for prosecution those responsible for abusing children.

- Ensure that provincial and district Action Committees for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor meet regularly, and identify the worst forms of domestic labor as a priority area.

- Recognize the link between the financial barriers to education and child labor, and identify and implement strategies to address obstacles to education that school fees and related costs create for poor children. Expand any existing programs that provide assistance to poor children who cannot access school to also include migrant children under 15 found to be working in the area.

To the Ministry of Manpower

- Immediately prioritize the drafting and public consultation on a Domestic Workers Law that reflects the protections outlined above, with the aim of completing a draft by mid-2009.

- Provide instruction and necessary resources to local Manpower offices to carry out their existing duties to investigate labor exploitation of child domestic workers.

To the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights and the Ministry of Women's Empowerment

- Design and implement a public awareness campaign on the Child Protection Act, the Domestic Violence Act, and the Anti-Trafficking Act that targets the police, prosecutors, the judiciary, civil society groups, and the general public.

To the police

- Reduce response time by the women's and children's unit when a complaint is filed by a domestic worker regarding abuse or exploitation. Sufficient information should be collected at the very first interaction with a victim to enable an investigation to be started immediately.

- Comply with the obligations under the Domestic Violence Act, in particular to provide temporary protection to a victim within 24 hours of knowing or receiving a report of violence in the household.

- Provide adequate resources and training to women's and children's units, and publicize their existence to the public.

- Design proactive community outreach and investigative strategies to carry out existing obligations under the law to identify hidden instances of exploitation and abuse of child domestic workers.

To prosecutors

- Ensure all prosecutors receive regular training on eliminating gender bias in their approach to cases of domestic violence, sexual assault, and other gender-based crimes against women and girls. Ensure all prosecutors conduct their functions without gender bias.

- Where feasible, consider the development of a unit of prosecutors who specialize in cases involving crimes against children or gender-based crimes against women.

To the TeSA129, police, and KPAI child hotlines

- Ensure hotlines are adequately staffed around the clock by trained personnel who can alert officials to extract children from abusive situations, provide safe shelter, medical treatment, and counseling.

To the Ministry of Education

- Recognize the link between the financial barriers to education and child labor, and identify and implement strategies to address obstacles to education that school fees and related costs create for poor children.

To the International Labour Organisation

- Advocate for the inclusion of special protections for child domestic workers during the drafting of the new treaty on decent work standards for domestic workers.

II. Methodology

Since 2004, Human Rights Watch has interviewed more than 200 people in Indonesia on the issue of child domestic workers. We have made field investigations in Java and Sumatra in the urban areas of Bandung, Bekasi, Depok, Jakarta, Medan, Pamulang, Semarang, Surabaya, Yogyakarta, and in two rural areas where child domestics are recruited, one outside Medan, and another outside Yogyakarta. We have spoken with 78 current or former child domestic workers age 11 and older.

On our most recent visit, in July 2008, Human Rights Watch visited Bandung, Bekasi, Depok, Jakarta, and Yogyakarta. We interviewed more than 90 people, including 21 current child domestic workers. All of the child domestic workers we interviewed were girls; the youngest girls were 13 years old, and the earliest that they had begun working as domestic workers was from age 11. We also interviewed an additional 13 former domestic workers about their experiences while they were still children.

We met with 19 representatives of non-governmental organizations or civil society groups; we have also been in email contact with non-governmental organizations based in Aceh and Cirebon. In addition, we spoke with one labor law professor and with representatives from the Jakarta office of the International Labour Organization. We talked with eight individuals from domestic worker recruitment and placement agencies; five of these conversations were held over the telephone anonymously either under the pretence of being a potential employer or potential child employee in order to better verify and evaluate the information provided by these agencies to these target groups. We also interviewed four individuals who work as recruiters of child domestic workers; one worked for an official agency, and the other three were transient vegetable vendors who recruited girls for some of the housewives with whom they trade. Human Rights Watch also made overt visits to three agencies that supply child domestic workers.

We met with three elected politicians and an additional 20 government officials, including representatives from the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, the Labor Division of the Ministry of Women's Empowerment, the Children's Division of the Ministry of Women's Empowerment, the program on child labor in the Ministry of Manpower, the Legal Bureau of the Ministry of Manpower, the Chief Prosecutor, the Jakarta Manpower Agency, the Yogyakarta Manpower Agency, the Mayor of Yogyakarta, the Chair of the Yogyakarta city legislature, the Chair of the Special Committee on the drafting of the Manpower Bill in Yogyakarta city legislature, the National Police, the Jakarta Police, and the Yogyakarta police.

Interviews were conducted either directly in English or in Bahasa Indonesia, or through the use of an interpreter.

Pseudonyms are used for all current and former child domestic workers quoted in this report.

In this report, the word "child" refers to anyone under the age of 18. The Convention on the Rights of the Child states: "For the purposes of the present Convention, a child means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier."[1] Although Indonesian law offers inconsistent definitions for majority, both Indonesia's Child Protection Act and Manpower Act also define a child as being a person under the age of 18.[2]

III. The Abuse and Exploitation of Child Domestic Workers–A Continuing Situation

In 2008, Human Rights Watch returned to Indonesia to assess developments in the treatment of child domestic workers since our original research on the topic in 2004. Worryingly, we found that child domestic workers continue to endure the same wide variety of abuses that we had identified then.

Although our 2005 report, Always on Call, documents these abuses comprehensively, testimonies from the girls we spoke with in 2008 indicate how abuses continue. This chapter provides a brief overview of the range of abuse and exploitation that child domestic workers continue to face in Indonesia. Other examples are cited in the chapters that follow.

During our most recent visit, Human Rights Watch again found that domestic workers often begin work below the age of 15, which is the legal age of employment. For example, we met girls like Ayu, whose testimony opened this report. Ayu was 13 years old when we spoke with her, but she was only 11 when she started working full time as a domestic worker.[3] Another girl we spoke with, Wulan, told us how her employer was aware that she was only 13 when hired.[4]

One labor recruiter-who claimed to recruit approximately 400 girls each year in exchange for earning 300,000 rupiah (US$30) per girl-started by insisting to us that she only ever recruits girls who are over 15 years old, "because there is a fine for anyone that finds work for children under 15."[5] Later, she confessed, however, that she will "help" girls who are under-15 who approach her if she knows the potential employer well.[6]

Girls continue to work extremely long days-typically 14 to 16 hours a day, but sometimes more-including early morning and late into the night. Sixteen-year-old Kemala told us, "I work from 4 a.m. until midnight. I am not allowed to rest."[7]

Most child domestic workers still never get a day off work. "A day off?" asked Dewi when sharing her experiences with her first employer, when she was 15 years old. "There's no such thing! Of course I have to do everything. It doesn't matter. The employer does not care no matter how tired I am. My employer is going to make me do everything."[8]

Despite these long hours, girls continue to earn wages well below the local minimum wage requirements for "formal" work in the same areas. Even without considering the discrimination in pay between child domestic workers and workers in the formal sector who benefit from minimum wage requirements, the exploitative nature of the low salaries paid to child domestic workers is obvious. Consider Dian, who explained the daily responsibilities she had during her first job at age 15:

I woke up at 4 a.m.… I would then clean, warm leftovers, make the [11-year-old] child's lunch, clean the car, and prepare lunch for my employer for work…. I had to wash the dishes. I cleaned the bathrooms. I spent a lot of time with the old lady. She has to get the sun, I had to prepare her food, and I had to bathe her and look after her…. I was allowed to nap from 1-2 in the afternoon…. The earliest [I would get to bed] was 10 p.m. In the evenings, I would clean the old lady's room. I have to help this old lady go to the toilet. Everything. The old lady is sick. She is diabetic, she has a heart condition, and she broke her leg. She needs a cane…. I never got a day off.[9]

One labor agency we spoke with in Jakarta informed us that their standard rate for a care-giver to the elderly was 1.2 million rupiah ($120) per month, another quoted us 1.3 million rupiah ($130).[10] Dian received just 300,000 rupiah ($30) per month.[11] Working a 17-hour day, seven days per week, this is equivalent to a wage of less than 6 cents an hour.

Physical and psychological abuse of child domestic workers remains a serious problem. Wani told us about the job she had from age 13 to 17:

If I made a mistake [my employers] would shout. They called me names very often, like 'stupid,' 'devil,' 'dumb,' and all other curse words. [My female employer] often hit me, sometimes she'd pinch me. Sometimes she would throw [little plastic] water pails at me. Sometimes she would push me to the wall. Slap me. Pinch me. Sometimes she would slap me twice a day…. Sometimes [I had bruises].[12]

Girl domestic workers also continue to be vulnerable to sexual abuse including rape by male employers or their male family members. For example, seventeen-year-old Kartika told us how she was raped by her male employer,[13] and Guritno told us about the employer she had when she was 15 years old:

I felt uncomfortable when [my employer's husband] would be naked outside his bedroom. So I started getting really scared whenever the children would go to school and the employer would leave, and I would be left alone with him…. He'd ask me, 'Do you want to see [my penis]?' He would do this every day that we were left alone. I wanted to tell the employer but I was scared we would get in a fight.[14]

IV. Current Domestic Legal Framework

This chapter briefly reviews the existing domestic laws that apply to the treatment of child domestic workers in Indonesia. The degree to which these laws are discriminatory, incoherent, and poorly enforced, are discussed in Chapter VI. The international standards to which Indonesia's national and local governments should adhere, are outlined in Chapter VII.

Criminal Code

Indonesia's Criminal Code prohibits many of the abuses perpetrated against child domestic workers, including abuse, assault, the use or the threat of the use of violence to coerce action, sexual harassment, rape, sexual assault, kidnapping, slave trading, trafficking, and murder.[15]

Child Protection Act of 2002

The Indonesian government passed the Child Protection Act in 2002 with the stated purpose of guaranteeing the rights contained in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.[16] The law defines a child as anyone under the age of 18 and prohibits economic or sexual exploitation of children, as well as violence and abuse of children.[17] The penalties for exploiting a child economically or sexually are a maximum of 10 years imprisonment and/or a maximum fine of 200 million rupiah (US$15,600).[18] Persons who commit acts of violence, including torture, against a child can be imprisoned for up to three years and six months, and/or fined a maximum of 72 million rupiah ($5,600).[19] The penalty increases if the child is seriously injured (five years imprisonment and/or maximum fine of 100 million rupiah ($7,800)) or dies (ten years imprisonment and/or maximum fine of 200 million rupiah ($15,600)).[20]

The law also promises every child the right "to rest and enjoy free time, to mix with other children of his/her own age, to play, [and to] enjoy recreation."[21]

Presidential Decree of 2002

In 2002, two years after ratifying the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, the Indonesian government, by Presidential decree, launched a twenty-year National Plan of Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor (National Action Plan). The plan identified children who are physically or economically exploited as "domestic servants," along with 12 other areas of child labor, as a worst form of child labor.[22]

The National Action Plan is divided into three phases with targets to be achieved in the first phase after five years, in the second phase after ten years, and in the third phase after twenty years. The objectives of the first phase of the National Action Plan for 2003-2007 were to increase public awareness of the worst forms of child labor; map the existence of the worst forms of child labor; and to eliminate the worst forms of child labor in five areas: children involved in the sale, production and trafficking of drugs; children trafficked for prostitution; and children involved in offshore fishing, mining, and footwear production.[23] In co-operation with the ILO, the government established programs aimed to eliminate the worst forms of child labor within these targeted areas.

The second phase of the National Action Plan, scheduled for 2008-2012, is intended to replicate models used to eliminate the worst forms of child labor in the first phase "in other areas"-including children who are physically or economically exploited as "domestic servants."[24]

As discussed in Chapter VI, assessments of the success of the first phase of the action plan have been mixed.

Manpower Act of 2003

The Manpower Act-Indonesia's primary labor law-deals with the issue of child labor by starting with the basic premise that no entrepreneur can employ a child under the age of 18.[25] The law then goes on to provide an exception for employing a child aged 13 to 15 to perform "light work" for up to three hours per day, as long as the parents grant their permission, the work does not interfere with the child's schooling, and as long as the work does not disrupt the child's physical, mental, or social development.[26] The law, on its face, makes no provision for children aged 16 and 17 to engage in either light work or general employment.

The law also prohibits anyone from employing and involving children in the worst forms of child labor, such as slavery or practices similar to slavery; jobs that use, procure, or offer a child for prostitution, pornography or gambling; jobs which use a child to procure, or involve a child for production and trade of alcoholic beverages, narcotics, or psychotropic substances; and all kinds of jobs harmful to the health, safety, and morals of a child.[27] The types of jobs which damage the health, safety, and morals of children are not defined in the Manpower Act, but were determined by a ministerial decree in October 2003,[28] discussed below.

The Manpower Act arbitrarily distinguishes between "entrepreneur" businesses and "employers," obligating only entrepreneurs to abide by requirements within the act for agreements, minimum wages, overtime, hours, rest, and vacation.[29] The law defines an "entrepreneur" as an "individual, a partnership or legal entity that operates a self-owned enterprise… [or] a non-self-owned enterprise." In contrast, an "employer" is defined as an "individual, entrepreneur, legal entities, or other entity that employ manpower by paying them wages or other forms of remuneration."[30] Employers of domestic workers are not considered entrepreneurs, and therefore domestic workers are not protected by these labor provisions.

Even though employers of domestic workers are therefore exempt from having to provide standard labor protections, there remains at least a basic obligation under the law for employers to provide "protection which shall include protection for their welfare, safety and health, both mental and physical" to those they employ, including domestic workers.[31] Employers who fail to provide such protections are liable to a criminal sanction of between one month and four years imprisonment and/or a fine ranging from 10 million rupiah to 400 million rupiah (US$985 to $39,360).[32]

Ministerial Decree of 2003

A 2003 Decree by the Minister of Manpower Regarding Types of Work that are Hazardous to the Health, Safety or Morals of Children stipulates that the minimum age of employment for non-hazardous work is 15.[33] The Decree bars only employers in the formal sector from employing children to work overtime.[34]

The Decree also prohibits children under the age of 18 from performing work that is hazardous to their health, safety, and morals.[35] Among the conditions of employment identified as posing a threat to a child's health, safety, and morals, includes working between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m. or working within a locked working place.[36] It is a felony to employ any child under such conditions, and anyone who does so is subject to imprisonment for two to five years, and/or a fine of between 200 million rupiah and 500 million rupiah ($19,700 and $49,250).[37]

Domestic Violence Act of 2004

The Domestic Violence Act prohibits physical, psychological, and sexual violence against a husband, a wife, children, family members living in the home, and persons working in the home, and provides for sanctions against perpetrators of the abuse.[38] Neglect of household members is also criminalized.[39] Live-in domestic workers are included in the law's protections as it encompasses individuals "working to assist the household and living in the household."[40] Under the law, the state is also required to prevent the occurrence of such violence, protect victims, and to prosecute the perpetrator. The law provides stiffer penalties to those available under the Criminal Code and lessens the evidentiary standard necessary to prove the relevant crimes in court, by stating that only one other form of admissible evidence is necessary to corroborate the testimony of the victim.

Anti-Trafficking Act of 2007

In April 2007, Indonesia enacted a new law to tackle domestic and international trafficking in persons.[41] The new law criminalizes the act of trafficking in person, as defined by article 1(1):

Trafficking in persons shall mean the recruitment, transportation, harboring, sending, transfer, or receipt of a person by means of threat or use of force, abduction, incarceration, fraud, deception, the abuse of power or a position of vulnerability, debt bondage or the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, whether committed within the country or cross-border, for the purpose of exploitation or which causes the exploitation of a person.[42]

The law makes clear that "exploitation" can include forced labor, forced service, slavery or practices similar to slavery, repression, extortion, physical abuse, sexual abuse, or the use of another person's labor for one's own profit.[43]

The 2007 law includes positive provisions for child victims and witnesses such as court sessions closed to the public, the right to be accompanied by a parent or guardian during examination, the examination of child victims and witnesses in the absence of the defendant, and the possibility to be examined outside of the courtroom.[44]

The fact that the new law does not enact all the protections provided to children under international law, and the lack of public awareness about this new law are fully discussed in Chapter VI.

V. Eight Enduring Myths

Indonesia's policymakers continue to harbor a number of misconceptions about child domestic workers. Many of the fallacies are the product of a lack of government monitoring and inquiry into child domestic labor or continuing discriminatory attitudes about the role of girls and women in society. These persistent erroneous beliefs are a key contributing factor to the widespread government reluctance to adequately address the issue of the abuse and exploitation faced by child domestic workers, either through the development of new policies, or the enforcement of existing laws. To the extent that many of these false perceptions are also shared by the general public, it emphasizes the need for the government and civil society groups to engage in long-term mass media public awareness raising campaigns. The eight most worrisome and widespread enduring myths are:

Myth 1: Domestic workers are "helpers" not workers

We never [consider] these domestic workers as real workers, [nor] as real laborers.

- Dwi Untoro, official, Jakarta Manpower Agency, Jakarta

Far too many government officials fail to consider domestic workers as genuine workers, instead belittling them by labeling them as "helpers." A senior official in Jakarta's Manpower Agency told us:

We haven't included domestic work in the [definition] of a worker…. They are different in their relationship to work. They stay in their houses. They eat what their master eats. And they go where their master goes.... If you are a worker you have a certain salary, certain rights, and you don't stay in the family. It's quite tricky. Historically, this kind of worker is not paid at all.[45]

The supervisor responsible for monitoring the implementation of labor laws at the Yogyakarta Manpower office explained to Human Rights Watch why she felt child domestic workers received different protections from other workers, such as child workers in a factory: "For the child domestic workers it is more about just helping their employer, not a company, but a person."[46]

Yet, as documented by Human Rights Watch, child domestics carry out activities that are taxing and productive, and deserving of being recognized as work. The child domestics Human Rights Watch interviewed typically worked 14 to 18 hour days, seven days a week, with no holidays, although some were allowed an annual one-week leave at Eid-ul-Fitr. Nearly all of the girls we interviewed were responsible for cleaning the house, laundering the entire household's clothes by hand, ironing the clothes, preparing the family's meals, and taking care of the employer's children.

Most of the girls we spoke with, like this 17-year-old domestic worker, were responsible for child care as part of their daily responsibilities. © 2008 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

For example, 13-year-old Cinta told us that she wakes up at 5 a.m. each day. After washing, she does the dishes, cleans the rooms, cleans the floor, sweeps, irons, and feeds and dresses her employer's four children, ages four, five, seven, and eight. Cinta goes to sleep at 10 p.m., and only gets one hour of rest each day. "I get very tired," she confessed.[47]

Bethari told us about the job she has had since she was 15. She described herself as "only a baby sitter." However, in addition to being the sole person looking after the four-year-old child of her employer while the parents work from 7:30 a.m. until 6 p.m., she also hand-washes all of the child's clothes, washes the dishes, does any leftover laundry, cleans the house, and cooks two or three meals per week.[48] For these tasks she receives 200,000 rupiah (US$20) per month.

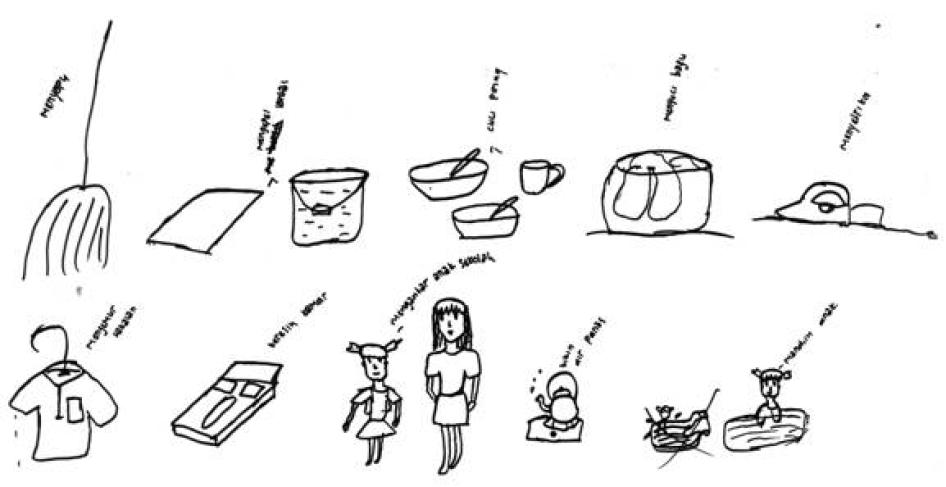

A 14-year-old domestic worker drew this picture to illustrate "All the tasks I do every day." These include sweeping, washing clothes, taking a child to school, and ironing.

The exertion of this work literally makes some girls ill. When she was just 11 years old, Ayu said, she had to quit her first job as a domestic worker because the strain was too much for her. She was responsible for looking after a nine-month-old baby-cooking, feeding and changing the baby, and putting the baby to sleep-and while the baby slept, doing the ironing. "I got sick. I got way too tired," she told Human Rights Watch.[49]

Many child domestic workers also assist their employers outside their homes. For example, Kartika was also required to work at her employer's small shop: "I would wake up at 4 a.m. and then work until 11:30 a.m. Then I would rest until 1 p.m., and then work again until 5 p.m. Then at 6 p.m. the shop would open and I had to work at the shop until 9 p.m."[50]

As Dian, a 17-year-old domestic worker who started working at age 15, pointed out,

People believe that domestic workers are second class citizens. Some people view us as helpers and not workers. But we are workers. We have a fixed salary. I actually play a big role-without my work at the home during the day, people who live in the house would not be able to do so-called 'formal work' in their offices. And yet government people still say that we are second class citizens![51]

Myth 2: Domestic work cannot be monitored

The problem is that domestic workers work in private homes.

- Nur Asiah, director of the program responsible for overseeing women and children, Ministry of Manpower, Jakarta

A circular argument often emerges in the justification of government officials that domestic workers cannot be regulated or protected because they are part of the "informal sector." However, the very definition of "informal" work is simply work that has not been regulated. It is not that governments are unable to regulate because domestic workers are informal labor; instead, it is because governments fail to regulate that domestic workers are informal labor.

By labeling all domestic workers as "informal," officials are abdicating their responsibilities to protect these workers. The label "informal" denigrates and minimizes the value of the work that domestic workers carry out, by implying that the government has no role to play in protecting individuals who engage in such work. This approach ignores the reality that the existence of a large informal labor sector is often the product of failed government policies, poverty, government failures to guarantee access to free and compulsory education, inappropriate and outdated regulation, dysfunctional labor markets, and a lack of political initiatives to find adequate solutions. It also ignores the historical reality of discrimination against women, children, and the poor, and the undervaluation of their labor.

Moreover, it is simply incorrect to suggest that employers of domestic workers are not subject to labor regulations. Although the current regulatory framework is both inadequate and discriminatory, as outlined in Chapter IV there remains at least a basic obligation under the law for employers to provide domestic workers "protection which shall include protection for their welfare, safety, and health, both mental and physical."[52] Although this obligation is particularly vague and lacks clear standards, until the government provides better protections, police and labor inspectors should ensure that employers provide at least these basic standards. Under the 2003 Decree by the Minister of Manpower, it is also a felony to require anyone under the age of 18 to work between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m., or within a locked working place.[53]

Another frequent excuse provided by policymakers for failing to do more to protect child domestic workers is the difficulty in regulating labor conditions within private homes.

Yet the Indonesian government has shown no sign of investigating or piloting possible solutions to this problem, despite various solutions proposed by both domestic and international organizations, and by best practices around the world. For example, employers could be required to register with the local neighborhood association (Rukun Warga and/or Rukun Tentangga) the name and age of each domestic worker employed in their homes, and these neighborhood associations could be authorized to monitor workplace conditions and to promptly report violations to the local Manpower office and the police.[54] Local government social workers could also be empowered to monitor workplace conditions.[55] Joint visits by both a labor inspector and social workers could also be considered. The police could be encouraged to use their powers to carry out investigations, or special civil investigators could be similarly empowered.[56] Inspections can also be prioritized for households with child domestic workers. Former domestic workers may have particular skills in finding exploited child domestic workers-particularly in public spaces such as markets, in parks, or at bus stations at the times of year when child domestic workers generally migrate to cities to find employment-and can also play an important role in designing appropriate approach techniques.[57]

Many girls begin work younger than allowed by Indonesian Law. This girl, who is 13 years old, began working when she was 11 years old. © 2008 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

Regardless of the exact inspection regime, research conducted by Human Rights Watch around the world indicates that strengthening workers' associations, labor resource centers, children's drop-in centers, and devising accessible complaint mechanisms can play an important role.

One method for receiving complaints from victims that has proved effective in other countries is the establishment of 24-hour hotlines, staffed by trained personnel, who can alert officials to extract children from abusive situations, provide safe shelter, medical treatment, and counseling. A number of hotlines have been established recently in Indonesia for children. However, Human Rights Watch tried calling three of these hotlines at various times of the day over different days with almost no success. The hotline "TeSA129" (Telepon Sahabat Anak; The Friend of the Child Telephone) is run out of the Ministry of Communication and Information, and is supported by the Social Department, the Ministry of Women's Empowerment, PT Telekom Indonesia, Child Helpline International, and PLAN International.[58] The hotline operates in Jakarta, Pontianak, Makassar, and Surabaya. Although their advertising posters and stickers do not indicate this, the line currently operates only 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Mondays to Fridays. We made twenty-three calls to TeSA129 and only two of these calls were answered.[59] To the hotline operated by the women and children's unit at the National Police, we made seventeen calls, of which only one was answered.[60] With the child hotline run by the Commission for the Protection of Children in Indonesia (Komisi Perlindungan Anak Indonesia), we called nineteen times and were answered on just two occasions.[61]

The fact that there is much yet to be done by these government agencies to ensure the most basic complaints mechanisms run efficiently is an indication that there are many practical steps that the government could undertake to monitor the treatment of domestic workers. It is not that inspections and monitoring are impossible to do, it is that the government is simply choosing not to prioritize the protection of these young workers.

Myth 3: Employers' ability to hire a domestic worker, even if they cannot afford the minimum wage, is more important than the child domestic worker's rights

If we regulate that domestic workers be paid a minimum wage, their employers who are lower-class factory workers would spend all they earn on their domestic workers.

- Nur Asiah, director for women and children, Ministry of Manpower, Jakarta

Nur Asiah, the director of the program responsible for overseeing women and children in the Ministry of Manpower, told Human Rights Watch that she could not extend equal labor protections to domestic workers and child domestic workers as afforded other workers because it would be too expensive to employers:

The difficulty [in extending existing labor law protections] is because these employers are not just upper- and middle-class people, but also lower-middle-class people. If you use the general labor law, employers would have to pay child domestic workers the minimum wage, and the lower-middle-class employers are also earning a living at the minimum wage…. It's difficult to regulate because these lower-class factory workers couldn't go to work if they did not have domestic workers to look after their children.[62]

Arguments against a minimum wage for child domestic workers because the costs of adhering to these labor standards may be unaffordable to some employers, almost presupposes that the government bears a responsibility to ensure all families can afford domestic help. Rather, the government is obliged to protect all individuals from exploitation and abuse. A private lawyer who works on behalf of a labor agency mediating disputes when employers fail to pay their domestic workers put it bluntly: "If you don't have the money, don't invite people to work in your home."[63]

This labor placement agency uses the fact that its domestic workers do not go home for the Eid-ul-Fitr holiday as a marketing point. © 2008 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

To the extent that policymakers believe that domestic work or child care is a necessity to enable others to engage in work outside the home then the government needs to consider pursuing alternative policies that do not depend on the exploitation and under payment of child workers. For example, other alternatives might include the creation of accessible, affordable child care options for families, making workplaces more flexible for working parents, or providing for more generous maternity and paternity leave.

Myth 4: Domestic workers do not need written contracts

[Having written contracts] would become a problem.

- Justina Paula Soeyatmi, Yogyakarta City Legislature member, and chair of the Special Committee on Manpower, Yogyakarta

Policymakers are reluctant to encourage written contracts for domestic workers. We spoke with one of the drafters of a proposed labor law in Yogyakarta city, and asked her why the draft law included an article that said that domestic workers "may" have written agreements with their employers, but did not require such contracts. She told us: "Maybe [having written contracts] is fine for housewives with high education, but uneducated housewives might be afraid…. If regulations are too strict, domestic workers might lose their jobs because people would not want to employ them."[64]

Human Rights Watch's research in Indonesia and in other countries indicates that the negotiation and conclusion of written contracts detailing the rights and obligations of both sides can be beneficial to both parties, as the process helps clearly define the relationship in advance and can serve as an important point of reference. This is the standard practice for most formal-sector employment worldwide.

One agent who places child domestic workers told us that he sees considerable benefit in requiring contracts: "Before we required contracts we had lots of problems…. Employers tended to deny that they had promised more money in salary. Now that it is written in a contract there are less problems like this."[65] Although it is true that oral contracts can be just as valid as written contracts under Indonesian law, as a labor law expert explained to us, "When they are written, they are more enforceable because then it's in black and white."[66]

The creation of a standard "model" contract could help alleviate the anxieties over the use of written agreements, and establish a minimum set of acceptable standards.

Two 17-year-old girls and a 22-year-old woman study how to become baby-sitters at an employment agency in Jakarta. © 2008 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

Seventeen-year-old Lestari was a rare exception in that she has a written contract with her employer. She said she was pleased with the arrangement: "[It specifies] my day off, a menstrual day off, Eid-ul-Fitr [holiday] off, [that I must receive] adequate food, adequate salary-it says 300,000 rupiah ($30) in my contract. It's important because it mentions what my job [responsibilities] are, and the employer also has to agree with what the contract mentions."[67]

Myth 5: Housework is not a nine-to-five job

The thing is, [child domestic workers] stay in the house. And whenever [the employer] needs something, they call her.

- Dwi Untoro, official, Jakarta Manpower Agency, Jakarta

Some government officials contend that housework is inherently a 24-hours-a-day activity, and therefore cannot be constrained to limited working hours. The apathetic attitude displayed by the Jakarta Manpower official in the quote above is particularly concerning given the fact that a 2003 Decree by the Minister of Manpower explicitly bans anyone under age 18 from working between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m., since such work poses "hazards on the health, safety, or moral[s]" of children.[68]

Yet many agents involved in the recruitment and placement of child domestic workers also adopt the attitude that child domestic workers can labor around the clock. One labor placement agent we contacted anonymously in Jakarta, as if we were a potential employer, told us that the standard hours for their domestic workers were from 6 a.m. to 9 or 10 p.m., but that if the employer's child woke up at night and wanted milk, then it was acceptable for the domestic workers to be expected to attend to that. A second agency told us that after being given a few weeks to settle in, domestic workers could be expected to work from 6 a.m. until 10 p.m., and can occasionally be asked to work as late as 11 p.m. A third agency told us that they do not involve themselves with such matters, and it was an issue to be discussed between the employer and the domestic worker.[69]

In the absence of any enforcement of the 2003 Ministerial Decree which bans children from working between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m., and without any other regulations mandating the maximum number of hours that a domestic worker can be made to work, employers are pushing child domestic workers to be at their beck and call from waking until sleep. Seventeen-year-old Elok shared with us her long daily schedule:

I wake at 5 a.m. and I clean. At around 7 a.m. I cook. Around noon and in the afternoon I sweep the front porch. Then I go back inside and iron. Then in the afternoon I prepare for dinner in the evenings. After 10 p.m. I go to bed. [I get] two hours of rest during the day…. If guests come to the house I work later. From 5 a.m. to 11 p.m.… Two colleagues [of my employer] routinely come around twice a week at night. I prepare them food and drinks.[70]

When we asked some girl domestic workers to draw for us the kind of tasks they have to do every day, they illustrated activities such as ironing, cleaning the floors, laundry, and child care.

Arguments that the nature of domestic work does not lend itself to regulations on working hours and rest days fail to acknowledge the government's obligation to protect domestic workers' rights to just and favorable work, health, and right to rest. No employee can be required to be constantly at the beck and call of his or her employer. If an employer wishes occasional additional work beyond regular hours, like in the case of Elok above when her employer's friends come over to drink late at night, then the employer must compensate the employee appropriately and additionally. If an employer genuinely requires around-the-clock assistance, then a second or third shift should be hired to cover.

Myth 6: A day off is unsafe and unwise

[Child domestic workers] don't know how to use a day off anyway.

- Recruiter and distributor of domestic workers, Jakarta

Since 2004, the Women's Empowerment Ministry has been advocating with the public to grant one day of rest per week for child domestic workers, but has had trouble achieving this recommendation in the absence of binding regulation since child domestic workers still remain under the complete control of their employers.[71] As one recruiter and distributor of child domestic workers in Jakarta told us, most employers are not inclined to give their domestic workers days off, reasoning that it is not standard practice, and since many domestic workers are migrants to the city, they "don't know how to get around"[72] and are thus unable to benefit from a day off. Some employers fear that their domestic worker might become pregnant, and that the employer will be held somehow liable. Some labor placement agencies advertise that their domestic workers do not go home during the Eid-ul Fitr holiday.

Most of the girls we spoke with never got a day of rest. "I didn't get any rest days in three-and-a-half years of work," Wani told us of the job she had from age 13 to 17.[73]

The girls whom we spoke with who were granted days off said they used them for rest or recreation. "Sometimes I get one day off a month and I go visit my aunt in Jakarta," Endah told us.[74] Seventeen-year-old Siti shared, "[If] I get days off, depends on my employer. [Maybe] one day a month. I go out to the zoo. Sometimes I just stay at home…. Just watch TV."[75] When we asked some girl child domestic workers to draw for us the activities that they enjoy during their free time, they sketched us pictures of themselves reading, going for walks, watching television, and singing.

Domestic workers need time off for their own well-being and for the well-being of those in their care. Many children lack the necessary experience, strength, and endurance to fulfill the tasks that they are assigned. Excessive work hours and lack of rest days directly affect the health and growth of children. The strain of this work literally makes some girls ill. A day off for domestic workers is also an issue of safety for employers and their families, as everyone performs better and with more care when given adequate rest. Children also require time to contact and connect with their own families, so as to prevent feelings of isolation and resulting psychological problems.

When we asked some girl domestic workers to draw for us the kind of activities they like to do when they have free time, they illustrated reading, going for walks, praying, listening to music, watching television, and singing karaoke.

One domestic worker recruitment and placement agent, who we telephoned anonymously as if we were interested in hiring a domestic worker, told us that it was acceptable to forbid a domestic worker from leaving the home, and informed us that the agency's contracts stated that domestic workers were not allowed to leave the employer's house without the employer's permission. When we telephoned another agency, this time under the pretence of being a girl interested in looking for a job, we were told that we would be "bound" to the job and unable to leave the house.[76]

One transient vegetable vendor we spoke with told us about one house he visits where the two domestic workers are locked into the house, where "the windows had metal bars installed on them". As a result he has to sell them vegetables through the bars and he told Human Rights Watch that he feared that if anything such as a fire were to happen, "They would just die inside. ... They wouldn't be able to get out."C[77]

Fifteen-year-old Ratu told us how she had to escape from her physically abusive employer:

At 11 p.m., my parents came to the house. But the employer didn't allow my parents to meet me. So my parents stayed outside the house waiting all night…. [The next morning] when I threw the garbage out I saw my mother outside of the house. I was on the second floor, and my mother was near the fence… The employer said "Your parents cannot pick you up until they go to the [employment] agent and get his permission.".... On the fence there's a wall with iron spikes on top, so I went down to the first floor. My mother asked me to jump the fence. My father caught me as I jumped the fence. I had to leave my belongings in the house. I left my clothes, things for prayers, sandals.... There was no other choice. Because I didn't feel comfortable in the house, I was abused, [my employer] was violent, so I had to jump the fence.[78]

Myth 7: This is "ngenger," so the girls are treated like family

I got different treatment. When there was a family gathering and people were eating, the employer ate first, and then I had to feed the children. And then after the children were full, only then did I get to eat.

- Dewi, talking about the job she had from age 15 to 17, Bekasi

Ngenger is a Javanese word that refers to a customary practice in Java whereby a child stays in the house of a distant relative or sometimes someone who is not a relative, but is considered as part of the family. Traditionally, the child would come from a poor family and the receiving family would fund the child's schooling and daily needs. In return, and as a sign of gratitude, the child would do some forms of housework.

In 2004, Rachmat Sentika, the then-deputy for child protection in the Ministry of Women's Empowerment told Human Rights Watch, "Our [Javanese] culture is ngenger. If [children] work in a house, they are regarded by employers as their own children and are sent to school in return for working in the house…. Sometimes they get no salary because the employer provides them food and accommodation."[79]

On our most recent visit, a number of government officials continued to express a similar attitude that the custom of ngenger was sufficient protection for child domestic workers and relieved government of any urgency in providing better protection from exploitation. For example, the Director for Women and Children in the Ministry of Manpower-who is leading the efforts to draft a new regulation for domestic workers-told us of the treatment child domestic workers usually receive: "Generally they're treated like family."[80]

Similarly, a member of the Yogyakarta City Legislature who is in charge of drafting a new law for the city that covers both child workers and domestic workers rejected the need for better labor protections. As she insisted to Human Rights Watch,

The NGOs are always proposing that we add detail to this [draft] regulation, but in Yogyakarta it is difficult to do this because domestic workers are considered not to be workers, but to be family…. So it can be said that most employers treat domestic workers well.… [And] if there is a violation of the regulation the employers [would] object if they had to deal with the police! Because they are not like workers but part of the family…. We have discussions with women and if there is a regulation that applies [to domestic workers] it will be difficult because they consider domestic workers part of the family.[81]

Our research indicates that current practices are a far cry from such romanticized notions.

When we put this proposition to the head of one of the largest domestic worker recruitment and placement agencies in Jakarta, he told us simply, "100 percent of my girls are treated as employees and not as family members."[82] His agency places more than 1,000 individuals into domestic jobs each year and about 80 percent of these placements are women and girls under age 20. He said, "[Whenever] politicians say this it is just their way to isolate the truth and pretend that [exploitation] does not exist, when in reality [domestic workers] are treated like slaves."[83]

This 17-year-old domestic worker is a rare exception in that she is able to attend a few hours of informal schooling one day each week. © 2008 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

The fact that the relationship between employer and domestic worker now commonly falls outside of the traditional practice of ngenger is also shown by the widespread practice of employers recruiting through commercial recruitment and placement agencies, or reliance on local vendors who draw upon their own personal connections. In this way, any kind of familial or personal connection or affiliation between the employer and the child domestic worker is lost. Instead, the primary concern of employers is the maintenance of their households, not the welfare of their employee.

Moreover, the motivation of an employer who recruits a child rather than an adult is often to find someone who will work for less, who will complain less, who is easier to order around, and who has fewer social connections.[84] These factors are also likely to make the domestic worker more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation and less able to protect herself.[85] Not every child domestic worker suffers to the same degree, but strong laws are needed to protect those at risk of mistreatment. As in the formal sector, many employees are treated well, but clear rules help prevent those employers who might mistreat their employees from doing so.

One positive sign from our most recent visit was that at least two government officials conceded the fallacy of this argument that the culture of ngenger afforded sufficient protections. On reading the quote made by his predecessor in 2004, the new Deputy Minister for Child Protection burst out in laughter:[86]

[Sure] it was so in our customs. But the progress of the years and the changes in [our] values continue to change until now. The relationship [between domestic worker and employer] is now not because of family but is economic. I send my daughter, but you pay me for my girl, and the income is for the family in the village. This relationship is now economic not family…. The employer [thinks] 'you should work for me' not go to school.[87]

Similarly, as the mayor of Yogyakarta conceded to us: "Now the culture has changed and poor children still work with rich families, but now they are treated strictly as workers but also as second-class citizens."[88]

Myth 8: This is not a big problem

I admit that there are some people who treat their domestic workers bad, but if we calculate the percentage, it's only small.

- Justina Paula Soeyatmi, Yogyakarta City Legislature member, and chair of the Special Committee on Manpower, Yogyakarta

A "child-friendly" room within one of the newly established "women's and children's" police units. © 2008 Bede Sheppard/Human Rights Watch

When we presented individual cases of child domestic workers who had been abused and exploited, an official in the Manpower office in Jakarta dismissed our concerns: "The situation is not very horrific."[89] Other officials, as demonstrated by the quote above, dismissed the scale of the problem as being too limited to deserve government redress.

Such comments by government officials underestimate the number of girls affected by the discriminatory nature of the existing labor laws, which, as described in the next chapter, provide basic labor protections to formal workers, but exclude jobs such as domestic work that are carried out by women and girls. It also ignores the inherently vulnerable position that this form of work-confined within a private house, separated from family and peers, frequently in a strange town, and for little money-places each girl when she engages in domestic work.

Accurately counting hidden workers-particularly when the employment of underage workers is a crime-is notoriously difficult. A survey conducted by the University of Indonesia and the International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor at the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 2002-2003 estimated that there were 2.6 million domestic workers in Indonesia, out of which at least 34 percent, or more than 688,000, were children.[90] In 2007, the Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics conducted a labor force survey that, while designed to undercount the number of child domestic workers, nonetheless suggested that out of 416,103 live-in domestic workers in Indonesia, more than 79,529 children, or 19 percent of the total, work as live-in domestic workers.[91]

VI. Continuing Failure of the Indonesian Government to Protect and Prevent Exploitation of Child Domestic Workers

It is so sensitive because everyone has these domestic workers, so everyone in government, in business, and officials are scared that if you regulate [these workers] then it will affect their own privileges.

-Women's rights NGO director, Jakarta

Although it is the employers or their family members who directly perpetrate the economic exploitation and physical and sexual abuse of child domestic workers, it is the Indonesian government and its officials that are continuing to fail to protect them by preventing exploitation, providing services and remedies to children, and fully prosecuting anyone who perpetrates exploitation and abuse. This chapter documents these government failures by examining the actions of national and local lawmakers, police, and prosecutors.

National government retains discriminatory labor law

The Indonesian government has failed to revise its labor laws, which continue to exclude domestic workers from the minimum protections afforded to workers in the formal sector, such as provisions for a minimum wage, limits on hours of work, rest, holidays, an employment contract, and social security. This exclusion facilitates the abuse and exploitation of domestic workers, and disproportionately affects women and girls who comprise the overwhelming majority of domestic workers.

The 2003 Manpower Act arbitrarily distinguishes between "entrepreneur" businesses and "employers," obligating only entrepreneurs to abide by laws governing work agreements, minimum wages, overtime, hours, rest, and vacation.[92] Employers of domestic workers are not considered entrepreneurs, and therefore domestic workers are not protected by these labor provisions.

As demonstrated in the previous chapter, no legitimate reason exists for the exclusion of domestic workers from these protections. A 2007 Labor Survey carried out by the Indonesian Bureau of Statistics indicates that around 97 percent of live-in child domestic workers are girls, while the majority of individuals working in the formal sector and therefore benefiting from the regulations on work hours and rest are male.[93] The exclusion of domestic workers from the labor protections therefore has a serious discriminatory impact against women and girls who predominantly perform such work and denies them equal protection of the law.

In 2005, the Ministry of Manpower began drafting a law for domestic workers that was intended to afford domestic workers stronger labor protections. The drafting process appeared to come to a stop, however, sometime in late 2005 or early 2006.[94] A staff member in the Ministry's law bureau who is involved in the drafting of the law informed us that she did not expect any further meetings to be held on the draft during 2008.[95] As of October 2008, the law did not appear on the official list of the government's upcoming legislation to be presented to the parliament (Program Legislasi Nasional).

With the domestic workers law stalled within the Ministry of Manpower, the Ministry of Women's Empowerment took the relatively unusual step of holding its own public hearings on the draft law in May 2007 and April 2008. The Ministry also produced two updated drafts of the law based on these public hearings, and has committed to further redrafting of the law, even though the primary responsibility for drafting labor-related legislation is formally within the purview of the Ministry of Manpower.[96]

One domestic worker recruitment and placement agent told us, "I was invited by Women's Empowerment to a meeting to discuss the draft [domestic workers law] but the Ministry of Manpower did not even turn up! How ironic is that-considering it is a law about labor!"[97] An official within the legal bureau of the Ministry of Manpower confirmed that no representative from the Ministry was present at the Women's Empowerment meeting "because of a time clash."[98]

The Women's Empowerment Ministry is not alone in being unable to coax any action out of the Ministry of Manpower on the domestic workers bill. The director of a Jakarta-based women's rights NGO told us, "[A coalition of NGOs] has asked the Ministry of Manpower to meet with us, but until now, they have not done so. Because they do not consider this matter important. They do not consider the people important…. This is not a priority for the Ministry of Manpower. It is not even their 13th or 14th priority."[99]

Local laws

In the vacuum of inaction at the national level, some provincial and district governments have undertaken efforts to regulate child laborers and domestic workers.

For example in 2007, Central Java passed a provincial law on child labor that prohibits employing children in the worst forms of child labor, and explicitly cites domestic work as an example of jobs that are prohibited.[100] North Sumatra Province also has a law on the worst forms of child labor,[101] West Java province has laws on child labor and trafficking,[102] while the provinces of North Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, North Sumatra, West Nusa Tenggara, and the district of Surabaya have local regulations on trafficking.[103]